It is a journey that starts in the far south of Chile, and has now reached the city of Derry in Northern Ireland.

The colourful patchwork

arpilleras of women not just from Chile but from places as far apart as Laos, the United States and Zimbabwe are on show at the Tower Gallery in Derry until mid-June 2015.

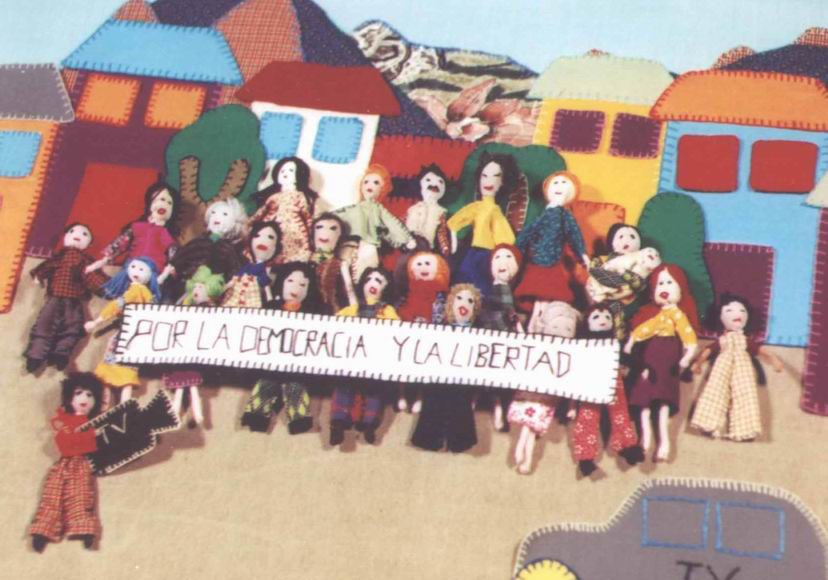

Arpilleras (the Spanish word for hessian or sacking) is a Chilean tradition in which small pieces of material are cut out to create images of everyday life and then embroidered onto pieces of cloth, originally backed by hessian.

They often also have small dolls stuck on and short texts embroidered on the backgrounds to add complexity.

The traditional

arpilleras were made by the women in the Isla Negra region of southern Chile.

The Nobel-prizewinning poet Pablo Neruda, a great collector of almost everything, was so impressed by this work that he arranged an exhibition of them in Paris during the 1960s when he was Chilean ambassador there.

“If it hadn’t been for Neruda,” says Chilean writer Damiela Eltit, who has studied the patchworks over the years, “the work of the arpillera women would probably never have become visible internationally. He gave them a kind of official approval.”

But it was after the 1973 coup by General Pinochet in Chile that the patchworks took on a new political dimension, as the curator of the Derry exhibition Roberta Bracic explains:

“From depicting scenes of everyday life, the patchworks began to be used as a means of quiet protest, as a repudiation of the dictatorship, and to show that ordinary people could survive, and share a narrative that would re-affirm life.”

In the late 1970s, the patchworks were promoted in Chile by the Catholic Church’s Vicaria de la Solidaridad as part of their defence of human rights. They began to circulate and be sold in many countries.

One of the early creators of the patchworks, Mireya Rivera Véliz explains what the work has meant to her:

“The arpilleras were a special way to interpret my pain and at the same time communicate it to others…my protest through the arpilleras has been silent, strong, desperate, full of unending tears.”

The work was also important as a collective effort, bringing women together to share their experiences – having family members who had disappeared, others who were in jail or in exile, economic hardship.

“Sharing their narrative was the essence of the solidarity movement, and showed that there was widespread resistance to the Pinochet dictatorship,” says Eltit.

She sees a stark contrast between these soft, colourful and female creations and the brutal male military order being imposed on Chilean society.

Robert Bracic also stresses the importance of colour in the patchworks. “They are made of scraps of material of any colour, anything that comes to hand. They are not meant to represent reality as you see it, but as you wish it could be. They’re not meant to be practical in any way, they simply say: this is my story, and invite a response in the viewer.”

The early patchworks were made from sacks which were cheap but also easy to fold up and hide if necessary. As Bracic explains:

“In the late 1970s in Chile if a woman was caught in possession of one of these arpilleras she could be tried in a military court for subversion. So many women carried them around folded up under their clothing.”

The powerful impact made by these quiet works of protest meant that their example was often taken up in other strife-torn parts of the world.

One woman in Laos whose work is included in the Derry exhibition says that for her and her fellow craftswomen:

“The patchworks are the archives of a truth the government wanted to suppress. Working together, we could share our stories, and feel we were not alone. Many times when the women were sewing, they would cry.”

Similar works have been produced by Zimbabwean women exiles in South Africa, and also in Northern Ireland as a response to the ‘troubles’ there that claimed more than 3000 lives.

Although democratic rule returned to Chile in the 1990, the arpillera makers still find topics such as domestic violence, the lack of healthcare, continuing poverty or the continuing protests for a fairer education around which they can base their colourful creations.

The traditional arpilleras were made by the women in the Isla Negra region of southern Chile.

The Nobel-prizewinning poet Pablo Neruda, a great collector of almost everything, was so impressed by this work that he arranged an exhibition of them in Paris during the 1960s when he was Chilean ambassador there.

“If it hadn’t been for Neruda,” says Chilean writer Damiela Eltit, who has studied the patchworks over the years, “the work of the arpillera women would probably never have become visible internationally. He gave them a kind of official approval.”

But it was after the 1973 coup by General Pinochet in Chile that the patchworks took on a new political dimension, as the curator of the Derry exhibition Roberta Bracic explains:

“From depicting scenes of everyday life, the patchworks began to be used as a means of quiet protest, as a repudiation of the dictatorship, and to show that ordinary people could survive, and share a narrative that would re-affirm life.”

In the late 1970s, the patchworks were promoted in Chile by the Catholic Church’s Vicaria de la Solidaridad as part of their defence of human rights. They began to circulate and be sold in many countries.

One of the early creators of the patchworks, Mireya Rivera Véliz explains what the work has meant to her:

“The arpilleras were a special way to interpret my pain and at the same time communicate it to others…my protest through the arpilleras has been silent, strong, desperate, full of unending tears.”

The work was also important as a collective effort, bringing women together to share their experiences – having family members who had disappeared, others who were in jail or in exile, economic hardship.

“Sharing their narrative was the essence of the solidarity movement, and showed that there was widespread resistance to the Pinochet dictatorship,” says Eltit.

She sees a stark contrast between these soft, colourful and female creations and the brutal male military order being imposed on Chilean society.

Robert Bracic also stresses the importance of colour in the patchworks. “They are made of scraps of material of any colour, anything that comes to hand. They are not meant to represent reality as you see it, but as you wish it could be. They’re not meant to be practical in any way, they simply say: this is my story, and invite a response in the viewer.”

The early patchworks were made from sacks which were cheap but also easy to fold up and hide if necessary. As Bracic explains:

“In the late 1970s in Chile if a woman was caught in possession of one of these arpilleras she could be tried in a military court for subversion. So many women carried them around folded up under their clothing.”

The traditional arpilleras were made by the women in the Isla Negra region of southern Chile.

The Nobel-prizewinning poet Pablo Neruda, a great collector of almost everything, was so impressed by this work that he arranged an exhibition of them in Paris during the 1960s when he was Chilean ambassador there.

“If it hadn’t been for Neruda,” says Chilean writer Damiela Eltit, who has studied the patchworks over the years, “the work of the arpillera women would probably never have become visible internationally. He gave them a kind of official approval.”

But it was after the 1973 coup by General Pinochet in Chile that the patchworks took on a new political dimension, as the curator of the Derry exhibition Roberta Bracic explains:

“From depicting scenes of everyday life, the patchworks began to be used as a means of quiet protest, as a repudiation of the dictatorship, and to show that ordinary people could survive, and share a narrative that would re-affirm life.”

In the late 1970s, the patchworks were promoted in Chile by the Catholic Church’s Vicaria de la Solidaridad as part of their defence of human rights. They began to circulate and be sold in many countries.

One of the early creators of the patchworks, Mireya Rivera Véliz explains what the work has meant to her:

“The arpilleras were a special way to interpret my pain and at the same time communicate it to others…my protest through the arpilleras has been silent, strong, desperate, full of unending tears.”

The work was also important as a collective effort, bringing women together to share their experiences – having family members who had disappeared, others who were in jail or in exile, economic hardship.

“Sharing their narrative was the essence of the solidarity movement, and showed that there was widespread resistance to the Pinochet dictatorship,” says Eltit.

She sees a stark contrast between these soft, colourful and female creations and the brutal male military order being imposed on Chilean society.

Robert Bracic also stresses the importance of colour in the patchworks. “They are made of scraps of material of any colour, anything that comes to hand. They are not meant to represent reality as you see it, but as you wish it could be. They’re not meant to be practical in any way, they simply say: this is my story, and invite a response in the viewer.”

The early patchworks were made from sacks which were cheap but also easy to fold up and hide if necessary. As Bracic explains:

“In the late 1970s in Chile if a woman was caught in possession of one of these arpilleras she could be tried in a military court for subversion. So many women carried them around folded up under their clothing.”

The powerful impact made by these quiet works of protest meant that their example was often taken up in other strife-torn parts of the world.

One woman in Laos whose work is included in the Derry exhibition says that for her and her fellow craftswomen:

“The patchworks are the archives of a truth the government wanted to suppress. Working together, we could share our stories, and feel we were not alone. Many times when the women were sewing, they would cry.”

Similar works have been produced by Zimbabwean women exiles in South Africa, and also in Northern Ireland as a response to the ‘troubles’ there that claimed more than 3000 lives.

Although democratic rule returned to Chile in the 1990, the arpillera makers still find topics such as domestic violence, the lack of healthcare, continuing poverty or the continuing protests for a fairer education around which they can base their colourful creations.

The powerful impact made by these quiet works of protest meant that their example was often taken up in other strife-torn parts of the world.

One woman in Laos whose work is included in the Derry exhibition says that for her and her fellow craftswomen:

“The patchworks are the archives of a truth the government wanted to suppress. Working together, we could share our stories, and feel we were not alone. Many times when the women were sewing, they would cry.”

Similar works have been produced by Zimbabwean women exiles in South Africa, and also in Northern Ireland as a response to the ‘troubles’ there that claimed more than 3000 lives.

Although democratic rule returned to Chile in the 1990, the arpillera makers still find topics such as domestic violence, the lack of healthcare, continuing poverty or the continuing protests for a fairer education around which they can base their colourful creations.