In March 2015, President Michelle Bachelet’s approval rating was the lowest since she took office a year earlier. The scandal in which her son Sebastián Dávalos and her daughter-in-law have been implicated; the economic slowdown; the shaky management of natural disasters such as the eruption of the Villarica volcano, forest fires in the south and floods in the north have tarnished the image and the support she enjoyed only a few months earlier.

When she returned to power in 2014, Ms. Bachelet faced a new mandate to carry out the kind of social, economic and political reforms that she had largely skirted round during her first period in office from 2006 to 2010.

Since the return of democracy in 1990, Chile has experienced spectacular growth, at an annual average of 5%, and has become the first South American country to join the OECD.

However, this strong growth has not meant the end of inequality, a socio-economic situation that came from the structures inherited from the Pinochet dictatorship between 1973 and 1990.

“We believe that a different and much more just Chile is possible. I want that the day I leave La Moneda, you will feel that your lives have changed for the better. Not just a bunch of statistics or indicators, but a better nation to live in, a better society for everybody”, Michelle Bachelet said in her first speech after taking office.

To achieve this better society, the president has proposed three main areas of reform: an end to the political legacy of the Pinochet era, a new model for education and a transformation of the tax burden.

Tax reform

The first of these reforms was a thorough overhaul of the tax system. Legislation was passed in September 2014 aimed at improving income distribution, generating new investment incentives and reducing tax evasion through changes to the income tax system.

With this reform, the Bachelet government hopes to collect an extra US$8.3 billion that would mainly be used to change the educational system, which was the next of her reforms.

Changes in education

In 2006, during the first mandate of Bachelet in La Moneda, thousands of students took to the streets demanding changes in the educational system. It was known as ‘La revolución de los Pingüinos’ –The Penguin Revolution–. These protests were even more widespread in 2010 and 2011 under the right-wing government of Sebastián Piñera.

As a result, President Bachelet has proposed widespread changes to the education system. The new legislation, passed in January 2015 and due to come into force early in 2016, seeks to abolish for-profit schools; eliminate educational institutions funded at the same time by the state and parents; and prohibits the selection of students by educational establishments according to socioeconomic and psychological parameters.

Welcoming the new proposals, Camila Vallejo, communist deputy and iconic student leader in the 2011 protests, said:“This project makes justice as it dismantles the three pillars of market laws. We are catching up with developed countries that are working in putting equality first.”

The end of binominal system

In January 2015, both houses of the Chilean Congress also passed into law the third area of the government’s reforms: the end of the binominal system. This was established in 1989 in the last days of Augusto Pinochet’s rule. This system was based on the election of two deputies in each of the districts. If an electoral list wanted to win both, it needed at least 66% of the votes.

This binominal system favoured the main political coalitions, the centre-left Concertación and the rightist Alianza, at the expense of the smaller political parties.

“Our democracy is taking a leap forward with this reform as it allows, after 25 years, the end of a unique electoral system in the world and which, of course, caused harm to Chilean democracy”, the president said after approval of the bill by the Senate.

Controversy

None of these reforms has been free from controversy. Right-wing parties appealed to the Constitutional Court over the political reform – an appeal that was rejected.

In conjunction with the business sector they have also criticized the tax reform as it “discourages investment”.

Criticism of the educational changes have come from the opposition parties, parents’ associations from private, publicly-funded schools, and even from student movements who consider the reform “insufficient”.

“If profit is bad, if selection of students is bad, if co-payment is bad, why then do not they eliminate the private schools where the Minister of Education Nicolás Eyzaguirre, the President Bachelet and the reform promoters send their children?” asked Carlos Peña, rector of the private Universidad Diego Portales.

What next?

President Bachelet seems determined to press ahead with her political agenda. In recent weeks, same-sex civil unions have been legalized, and a bill to decriminalize abortion in some cases was sent to Congress in February 2015.

Although the opinion polls may show that her wish to push through her wide-ranging reforms has raised hackles in some sectors of Chilean society, she is unlikely to change course in the next year, and continues to enjoy the support of her allies in Congress.

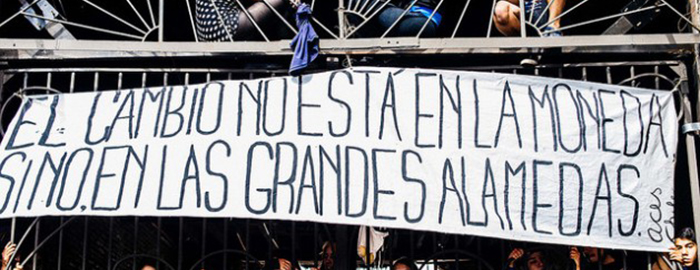

Main image: ‘Change is not in the Moneda, but on the broad avenues’ –an allusion to Salvador Allende’s famous last broadcast on 11 September 1973, when he said: ‘Sooner rather than later the broad avenues will be re-opened where people can march freely to build a better society’. La Moneda is the presidential building in central Santiago. Photo: IPS