LAB Editor Mike Gatehouse describes the experience of living in Chile under Popular Unity, the brutality of the coup and its aftermath, and the lasting legacy of neo-liberalism it has left. The article was commissioned by Red Pepper, and the original can be read here.

Versión en castellano. The article has now been translated into Spanish by Christine Lewis and posted on Rebelión.org. It can be read here.

I arrived in Chile at almost exactly the half-way point of the Popular Unity government. Salvador Allende had been elected President on 4 September 1970, at his fourth attempt at the presidency, heading a coalition of his own Socialist Party, the Radical Party (like Britain’s Labour Party, an affiliate of the Socialist International), the Communist Party and several smaller parties, one of them a splinter from the Christian Democrats.

The mood in the country in March 1972 was still quite euphoric, following substantial and hugely popular achievements such as the nationalisation of Chile’s copper mines and the pursuit of a more radical land reform. People still felt that now, at last, they had a government which belonged to them and would bring real and irreversible improvements for the poor and the dispossessed. In the words of the Inti-Illimani song: ‘Porque esta vez no se trata de cambiar un presidente, será el pueblo quien construya un Chile bien diferente’ —This time it’s not just a change of President. This time it will be the people who will build a really different Chile.

Radicalised culture

Chile was an intensely exciting place to be. Everyone was ‘comprometido’ —committed, involved. There was no room for being in the words of the Victor Jara song, ‘ni chicha, ni limonada’ —a fence-sitter, neither beer nor lemonade. Political debate was constant and ubiquitous among all ages and classes of people of the left, centre and right. Newspapers (most of the principal ones still controlled by the right), magazines, radio and TV discussed every action of the government, every promise made by Allende and his ministers and every move of the opposition with a depth, sophistication and venom almost unimaginable in Britain today.

One of the many paintings by the Brigada Ramona Parra which blossomed on walls throughout Chile.

The changes were not only political, they were profound changes in the national culture. Most of the popular singers, many actors, artists, poets and authors identified closely with Popular Unity and considered themselves engaged in a battle against the imported, implanted values of Hollywood, Disney, Braniff Airlines, the ‘cold-blooded dealers in dreams, magazine magnates grown fat at the expense of youth’ in the excoriating words of Victor Jara’s song ¿Quien mató a Carmencita? There was a vogue for playing chess and in cafés and squares you would see people earnestly bent over chess-boards while conducting vehement political debates.  The national publisher Quimantu (the old ZigZag company, bought by the government in 1971) was printing a vast range of books, produced and sold at low prices, to enable all but the poorest to own books, enjoy reading and have access to literature. In the two years of its existence it produced almost 12 million books, distributing them not only in bookshops, but street news-kiosks, buses, through the trade unions and in some factories.

The national publisher Quimantu (the old ZigZag company, bought by the government in 1971) was printing a vast range of books, produced and sold at low prices, to enable all but the poorest to own books, enjoy reading and have access to literature. In the two years of its existence it produced almost 12 million books, distributing them not only in bookshops, but street news-kiosks, buses, through the trade unions and in some factories.

Dark clouds

But dark clouds were beginning to gather. The CIA had already attempted a coup in 1970, with a botched kidnap attempt ending in the murder of General Schneider, commander-in-chief of the Chilean army. ITT and other US corporations were busily urging more decisive intervention on the State Department. There was a vast increase in funding to opposition groups in Chile and the price of copper, Chile’s crucial export, was being manipulated on the world market. The economy was beginning to falter, and inflation to climb.

In October 1972 the owners of road transport staged a massive lockout (still, mistakenly, called ‘the lorry-drivers strike’), paralysing road transport, attacking or sabotaging the vehicles of any who continued to work and paying a daily wage well in excess of normal earnings to owner-drivers who brought their lorries to the road-side encampments of the strike. The atmosphere of these was similar to those of the refinery blockades in Britain in 2000, but far more serious and violent. Food, oil, petrol and other necessities ran short.

I spent some of my free hours unloading trains in Santiago’s Estación Yungay, alongside teams of volunteers organised by the Chilean Young Communists and other groups.

The lockout subsided, and all attention was turned for the next few months on the mid-term congressional elections due in March 1973. Despite a concerted opposition media campaign to denounce growing food shortages and economic difficulties which were affecting the living standards of many workers, Popular Unity increased its share of the vote to 43.2 per cent.

By now, however, the Christian Democrat party had turned decisively to the right and began to identify more and more closely with the parties of the traditional right. Virulently anti-communist and sometimes anti-semitic messages became more frequent in their newspaper, La Prensa. Together, this right-dominated block held the majority in both Senate and Chamber of Deputies and could block any legislation. Their messages were that Popular Unity meant ‘the way to communism via your stomach’, in other words by hunger; and that socialism meant promoting envy and hatred (of the rich).

Violence of the wealthy

The now united opposition decided that if democratic votes would not provide the results it required, it would resort to violence and call on the military to intervene. Government buildings and institutions were targeted by arsonists, and sabotage of the electricity network brought frequent black-outs. I watched gangs of young middle-class men in Providencia, one of the wealthier avenues of Santiago, halting trolley-buses and setting fire to them.  On June 29 the No.2 Tank Regiment headed by Colonel Souper and backed by the leadership of the fascist group Patria y Libertad, staged an attempted coup. Tanks surrounded La Moneda, the presidential palace in the centre of Santiago. But the rest of the armed forces failed to move in support and the coup failed. I spent that day with my friend Wolfgang, a film-maker at the State Technical University, peering round street corners and trying to film the action as it developed.

On June 29 the No.2 Tank Regiment headed by Colonel Souper and backed by the leadership of the fascist group Patria y Libertad, staged an attempted coup. Tanks surrounded La Moneda, the presidential palace in the centre of Santiago. But the rest of the armed forces failed to move in support and the coup failed. I spent that day with my friend Wolfgang, a film-maker at the State Technical University, peering round street corners and trying to film the action as it developed.

We could not tell at the time if this was a dress rehearsal or a false start by a group of hot-heads. Our relief at its failure was short-lived: it was immediately clear that worse lay ahead. At my work-place, the Forestry Institute, we began to take turns to mount guard at night to protect the buildings against sabotage. The institute’s distinctive Aro jeeps had been ambushed on roads in the conservative south of Chile and the drivers beaten up.

In the poor neighbourhood where I lived, close to the centre of Santiago, we had set up a JAP, a food supply committee, which aimed to suppress the black market, discourage hoarding and ensure that basic necessities such as rice, sugar, cooking oil and some meat, were distributed to local residents at official prices. We had enrolled 1,200 families in an 8-block area, and the weekly general meetings were attended by 400 or more. We worked with the owners of the small corner grocery stores common in that area. But they had no love for us.

Military rebellion

The country was slipping into a de facto state of civil war. Allende attempted to stabilise the situation by including military officers in his cabinet, but his loyal army chief, General Prats, was forced to resign when a group of wives of other senior generals staged a demonstration outside his house, accusing him of cowardice. His replacement was General Augusto Pinochet, at that time still believed to be loyal to the constitution.

By early September 1973, we fully expected a crescendo of right-wing violence, a military rebellion, further coup attempts. Popular Unity supporters marched in a vast demonstration on 4 September, taking hours to pass in front of the Moneda Palace, where a desperately tired and grim-faced Allende stood to salute his supporters.

But nothing had prepared us for the swiftness, the precision and the totality of the coup that began in Valparaiso on the night of 10 September and had gained complete control of the government, all major cities, airports, radio stations, phones, transmitters and communications by 3pm on the 11 September.

In the Instituto Forestal, we met in the canteen. Most people left to go home, collect children from school, ensure the safety of their families. Some perhaps had orders from their parties to go to particular points of the city, to defend, to await orders, possibly to take up arms. A group of us stayed on to guard the buildings until the military curfew made it impossible for us to leave. The radio broadcast only military music and bandos, military communiqués, read in a clipped, cruel, mechanical voice, declaring an indefinite 24-hour curfew, reading a list of names of those who must hand themselves in immediately to the Ministry of Defence, and justifying the ‘military pronouncement’.

Torture and killings

At first we believed that there would be resistance, that the armed forces would divide, even that General Prats was marching from the south at the head of regiments loyal to the constitution. But none of this occurred. Pockets of resistance in industrial areas of the cities were swiftly and brutally eliminated. Some military officers were arrested, others fled the country, but there was no significant rebellion. The parties of Popular Unity and the MIR hunkered down for underground resistance but, having worked publicly and openly for so long, most of their existing leaders were instantly identifiable and were soon arrested or killed.

Together with other non-Chileans, I hid that night in the outhouse of a colleague who lived near the Instituto. Returning next morning we found the institute empty, with signs of doors having been forced and some bullet marks. A military patrol had come during the night and arrested the director and those who had remained on guard. We went through the buildings, office by office, removing all lists of names, trade union membership, party posters and badges, everything that we supposed might incriminate our colleagues. It was hard: everything that had been normal, routine, legal, was now illegal, dangerous, potentially lethal.

Later, some of the cleaners arrived and warned us to leave immediately: it was likely that the military would return and arrest us. They took us across the fields to the shanty-town where they lived and, at considerable risk to themselves and their families, hid and fed us in their houses until the curfew ended.

The next days were spent living in limbo, moving from one friend’s house to another. Of my two Chilean flatmates, one had been arrested on the 12 September in the State Technical University, along with hundreds of students and academics and taken to the Chile Stadium, where Victor Jara was tortured and shot. Wolfgang managed to escape and later would come as a refugee to Britain. The other, Juan, had sought asylum in the Swedish Embassy.

Complete purge

The scale and totality of the coup is hard to grasp. From the first, the military sought to replace every single public official from ministers, through provincial governors, university rectors, right down to small town mayors and secondary school heads. The new appointees were mostly serving or retired military officers or those in their direct confidence.

University departments (especially sociology, politics, journalism) were purged or closed and whole degree courses abolished. Libraries and bookshops were ransacked and books burned. Blocks of flats in central Santiago were searched and all suspect books (including mine) thrown by soldiers from the windows and burned in the street below. All political parties were declared ‘in recess’ and all those of Popular Unity and the left were banned, with their offices and property seized. The entire national electoral register was destroyed.

Our flat had already been raided twice by police, after right-wing neighbours claimed we had an arsenal of weapons stored there. Unwisely I returned, ten days after the coup, to collect clothes and was just leaving when the police blocked off the street and an armed patrol arrested me.

At the comisaría, the local police station, there was an atmosphere of hysteria. The carabineros there had divided and fought a battle on the day of the coup, between those loyal to the constitution and supporters of the coup. The survivors had been on duty almost continuously and been fed with rumours that ‘foreigners had come to Chile to murder their families’. Improbably, they accused me, despite my fair hair and blue eyes, of being a Cuban extremist. A pile of books, perhaps including mine, was burning in the courtyard and the smoke blew in through the bars of the cell where I was held.

In the National Stadium

Later that day they took me to the National Stadium, the vast national football and sports arena. The entrance was thronged with groups of prisoners being brought in from the four points of the capital. There was a large group in white coats, doctors and nurses from one of the main hospitals, arrested because they had refused to join right-wing colleagues the previous month in a strike against the government.

We were herded into changing rooms and offices. Soldiers manned machine-gun positions along the corridor which ran the full circuit of the stadium below the stands. We were 130 in our camarín, a team changing room, only able to lie down to sleep at night by lining up in rows and dovetailing heads and feet. Next to us was a cell with women prisoners, some of whom had been horribly abused and tortured, but whose morale and singing would sustain us in the coming days.

Photographs of the period tend to show prisoners sitting in the stands. But these were only a fraction of the total number, while many more remained in the cells below and those selected for interrogation, torture and elimination were taken to the adjacent velodrome.

I was lucky. My family and friends had informed the British Embassy that I was missing, and on my seventh day in the Stadium the British Consul arrived to obtain my release. I hoped to stay in Chile but with no documents and no job (all foreigners at the Institute had been indefinitely suspended by the new military-appointed director) I had little choice but to leave. Most others were much less fortunate. The Brazilian engineer next to me in the camarín was taken out for interrogation, hooded, beaten around the ears with a wooden bat until he could scarcely hear and questioned by both Chilean and Brazilian intelligence. I told Amnesty International about him, but we could never discover what became of him.

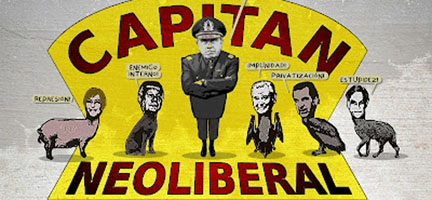

Neoliberalism starts here

Returning to Britain, I became involved with the Chile Solidarity Campaign, just being formed with backing from Liberation, the main trade unions, the Labour and Communist Parties, IMG, IS and many others from the churches, academics, artists, musicians and theatre people. At the time, we believed that the dictatorship would be brief, and I personally hoped and expected to return to Chile and resume my life there.

What none of us sufficiently understood was that the Pinochet regime was much more than the sum of its troops, its armaments and repression. It was an entire economic project, perhaps the first full-on attempt to implement a neoliberal revolution by means of the extreme shock of military coup and dictatorship. But the power that underpinned it lay not in Santiago’s Ministry of Defence, but in Washington and Chicago, in corporate headquarters, banks and think-tanks, in the City of London, Delaware and the budding off-shore empires. As so brilliantly documented by Naomi Klein in The Shock Doctrine, these would come to dominate not just Chile, but the states and economies of most of the developed world, and the recent recession notwithstanding, they dominate them still.

The fight against this globalised economic dictatorship has barely begun. Even in Chile, more than 20 years after the end of the Pinochet regime, the thousands of students who have taken to the streets in the past few years are clear in their demands: for an end to the neoliberal model in education and other public services and for the resumption of universal provision as a human right.