Aleyda has a history. Brought up in the home of Sandinista revolutionaries, she nonchalantly tells me how, in her childhood, she and brothers played with weapons, real weapons. The ones that her father used to fight the Somoza dictatorship. Her father, a founder member of the Sandinista National Liberation Front in the 1960s, was among thousands who took up arms and defeated the Somoza dictatorship in July 1979. The small Aleyda watched the celebrations on TV from neighbouring Honduras, where she lived in exile while her father fought. She saw the junta parade past, the junta that brought together Sandinistas and non-Sandinistas, all united to liberate Nicaragua from the cruel and pantomime-like dictatorship of the Somoza dynasty, whose soldiers and police bullies massacred Nicaraguans while at the same time, in bizarre television interviews, they invited tourists to visit their country.

Enjoying a late supper of meat, sausages, black beans and fried cheese on a hot and humid Managuan night, in a restaurant where a singer bellows out traditional Nicaraguan songs, Aleyda comes to life when she remembers the good old days of Utopia. And she looks sombre and sad when she says that those days are over. She had visited Cuba, where many other Sandinistas trained along with her father, counted the hours and minutes he was absent helping to write history with a machine gun, joined the party and believed, like many of us did, that the revolution would never end. But, when Aleyda’s father died 11 years ago, after he reached the rank of Sub-comandante in the Interior Ministry, he felt he had wasted his time in the struggle. Aleyda finds it difficult to talk about it, her eyes moistening with tears that she tries to repress, to no avail. She went quiet and I decided that I should respect her silence.

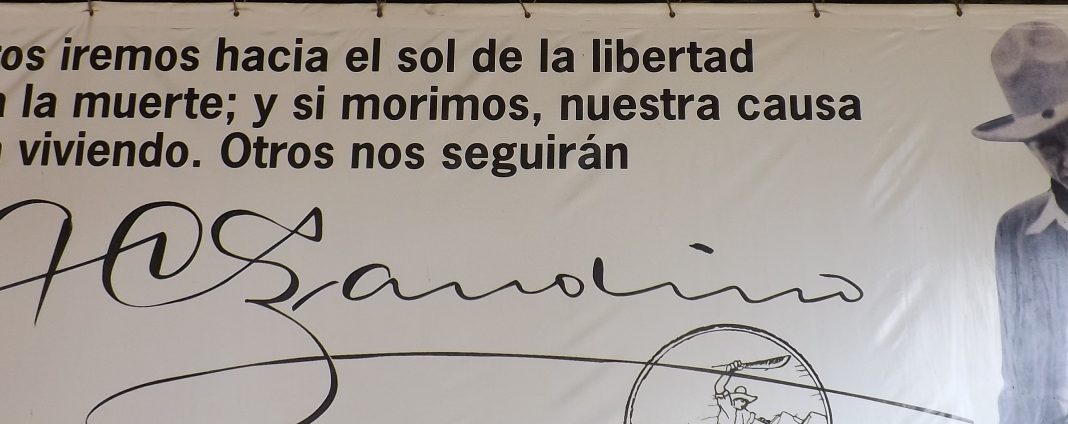

Walking the streets of Managua, nothing suggests that this was the capital of a country where once olive-green guerrillas walked the streets, not a museum to remember the struggle from the time of Sandino in the late 1920s to the creation of the FSLN and the final victory, when the city filled with red and black flags and gigantic posters of Sandino himself, with his big hat and his hands on his hip, holding a gun. In Granada, a few kilometres from Managua, where there was an uprising during the struggle, most buildings suggest a colonial past rather than a revolutionary present.

Nicaragua has changed from the time of the Sandinista Revolution, and the Daniel Ortega who runs his country now, for a second time since he was elected in 2006, is no more the moustachioed comandante dressed in olive-green uniform delivering anti-imperialist speeches but a balding old man who has had to ally himself with former enemies in order to govern.

Daniel Ortega is pretty much alone. Most of the nine comandantes who formed the Front’s national leadership have abandoned him, unhappy with his ruthless and highly personalistic way of ruling, his attempts to reinvent Sandinismo into “Orteguismo” and his move to the right, despite his left-wing rhetoric. Dora María Téllez, Henry Ruíz and Víctor Tirado, three of the members of the group of nine comandantes, are his political enemies now. Luis Carrión is a member of a dissident Sandinista movement and Jaime Wheelock runs a think-tank. Poet Ernesto Cardenal and former vice-president Sergio Ramírez all have left the FSLN to join other Sandinista organisations and are highly critical of Ortega. One of the historic leaders of the Frente, Tomás Borges, who remained loyal to the president, has died and another loyalist, Bayardo Arce, is now a businessman and an Ortega adviser. Even Ortega’s brother, Humberto, the once powerful defence minister, has turned his back on Daniel and now lives in Costa Rica.

Aleyda believes that Ortega benefits from what she calls the “hard core vote”, a loyal and 35% of the population who would vote for him no matter what. It seems that the 1990 defeat caused the implosion of the Sandinista movement. Two parties, the Movement for the Sandinista Renovation and the Sandinista Renewal Movement, have split from the FSLN and claim to speak on behalf of the ideals that deposed the Somoza dictatorship.

Aleyda has a history. Brought up in the home of Sandinista revolutionaries, she nonchalantly tells me how, in her childhood, she and brothers played with weapons, real weapons. The ones that her father used to fight the Somoza dictatorship. Her father, a founder member of the Sandinista National Liberation Front in the 1960s, was among thousands who took up arms and defeated the Somoza dictatorship in July 1979. The small Aleyda watched the celebrations on TV from neighbouring Honduras, where she lived in exile while her father fought. She saw the junta parade past, the junta that brought together Sandinistas and non-Sandinistas, all united to liberate Nicaragua from the cruel and pantomime-like dictatorship of the Somoza dynasty, whose soldiers and police bullies massacred Nicaraguans while at the same time, in bizarre television interviews, they invited tourists to visit their country.

Enjoying a late supper of meat, sausages, black beans and fried cheese on a hot and humid Managuan night, in a restaurant where a singer bellows out traditional Nicaraguan songs, Aleyda comes to life when she remembers the good old days of Utopia. And she looks sombre and sad when she says that those days are over. She had visited Cuba, where many other Sandinistas trained along with her father, counted the hours and minutes he was absent helping to write history with a machine gun, joined the party and believed, like many of us did, that the revolution would never end. But, when Aleyda’s father died 11 years ago, after he reached the rank of Sub-comandante in the Interior Ministry, he felt he had wasted his time in the struggle. Aleyda finds it difficult to talk about it, her eyes moistening with tears that she tries to repress, to no avail. She went quiet and I decided that I should respect her silence.

Walking the streets of Managua, nothing suggests that this was the capital of a country where once olive-green guerrillas walked the streets, not a museum to remember the struggle from the time of Sandino in the late 1920s to the creation of the FSLN and the final victory, when the city filled with red and black flags and gigantic posters of Sandino himself, with his big hat and his hands on his hip, holding a gun. In Granada, a few kilometres from Managua, where there was an uprising during the struggle, most buildings suggest a colonial past rather than a revolutionary present.

Nicaragua has changed from the time of the Sandinista Revolution, and the Daniel Ortega who runs his country now, for a second time since he was elected in 2006, is no more the moustachioed comandante dressed in olive-green uniform delivering anti-imperialist speeches but a balding old man who has had to ally himself with former enemies in order to govern.

Daniel Ortega is pretty much alone. Most of the nine comandantes who formed the Front’s national leadership have abandoned him, unhappy with his ruthless and highly personalistic way of ruling, his attempts to reinvent Sandinismo into “Orteguismo” and his move to the right, despite his left-wing rhetoric. Dora María Téllez, Henry Ruíz and Víctor Tirado, three of the members of the group of nine comandantes, are his political enemies now. Luis Carrión is a member of a dissident Sandinista movement and Jaime Wheelock runs a think-tank. Poet Ernesto Cardenal and former vice-president Sergio Ramírez all have left the FSLN to join other Sandinista organisations and are highly critical of Ortega. One of the historic leaders of the Frente, Tomás Borges, who remained loyal to the president, has died and another loyalist, Bayardo Arce, is now a businessman and an Ortega adviser. Even Ortega’s brother, Humberto, the once powerful defence minister, has turned his back on Daniel and now lives in Costa Rica.

Aleyda believes that Ortega benefits from what she calls the “hard core vote”, a loyal and 35% of the population who would vote for him no matter what. It seems that the 1990 defeat caused the implosion of the Sandinista movement. Two parties, the Movement for the Sandinista Renovation and the Sandinista Renewal Movement, have split from the FSLN and claim to speak on behalf of the ideals that deposed the Somoza dictatorship.

For those of us who grew up politically in the cradle of the Sandinista revolution, only the second revolutionary victory in Latin American soil, the divisions of the Sandinistas are a sad spectacle, a reminder that times have changed and that even the most solid revolutionary tradition can be the victim of inflated egos and petty-minded ideological quarrels.

Managua still has the scars of the revolution, but they are, in many ways, hidden from public view. Unlike other cities, such as Havana or Caracas where gigantic posters of Fidel or Chávez cover buildings and bridges, Managua is simply a city without a dominant personality. One needs to climb the hill that surrounds Lake Nicaragua to see the old presidential palace, damaged during the 1972 earthquake, that became the torture centre of the tyranny. After the 1979 victory, the people went to the old Somocista jail and destroyed it. Today, a museum constructed in the remains of the prison reminds people of the torture, the kangaroo trials, the executions. From that prison, in August 1978, dozens of political prisoners were liberated after the famous Comandante Cero took over the congress building and held hostage la crème de la crème of the dictatorship – Operation Pigsty, it was called – to demand that those who had fought against the Somoza dynasty, including Tomás Borge, be freed. A giant silhouette of Sandino, designed by the poet-priest Ernesto Cardenal, has been erected at the top of the hill, gazing down on the new Managua, with its tall buildings, parks and shantytowns. The big face of Sandino, that hung from the National Palace on 19 July 1979, surrounded by jubilant crowds of liberated Nicaraguans, stares at the visitors, alone in a corner of that open-air museum of horror.

For those of us who grew up politically in the cradle of the Sandinista revolution, only the second revolutionary victory in Latin American soil, the divisions of the Sandinistas are a sad spectacle, a reminder that times have changed and that even the most solid revolutionary tradition can be the victim of inflated egos and petty-minded ideological quarrels.

Managua still has the scars of the revolution, but they are, in many ways, hidden from public view. Unlike other cities, such as Havana or Caracas where gigantic posters of Fidel or Chávez cover buildings and bridges, Managua is simply a city without a dominant personality. One needs to climb the hill that surrounds Lake Nicaragua to see the old presidential palace, damaged during the 1972 earthquake, that became the torture centre of the tyranny. After the 1979 victory, the people went to the old Somocista jail and destroyed it. Today, a museum constructed in the remains of the prison reminds people of the torture, the kangaroo trials, the executions. From that prison, in August 1978, dozens of political prisoners were liberated after the famous Comandante Cero took over the congress building and held hostage la crème de la crème of the dictatorship – Operation Pigsty, it was called – to demand that those who had fought against the Somoza dynasty, including Tomás Borge, be freed. A giant silhouette of Sandino, designed by the poet-priest Ernesto Cardenal, has been erected at the top of the hill, gazing down on the new Managua, with its tall buildings, parks and shantytowns. The big face of Sandino, that hung from the National Palace on 19 July 1979, surrounded by jubilant crowds of liberated Nicaraguans, stares at the visitors, alone in a corner of that open-air museum of horror.

Under Ortega, Nicaragua has one of the most hard-line policies on therapeutic abortion in Latin America, neo-liberal policies keep the business sector happy and nothing moves without the permission of Rosario Murillo, the powerful wife of Daniel Ortega. From the silent wife of a revolutionary leader in the 1980s, she has become the power behind the throne. A minister, for instance, cannot give an interview to the media without getting authorisation from the Head of Government Communications, Rosario Murillo. No more collective decisions are taken by the FSLN leadership or by the community organisations that the Sandinistas created and cultivated after 1979. On Sunday, Ortega’s stepdaughter, who some years ago accused her stepfather of rape, gave an interview in which she talked about the hostility that her family faced for daring to expose Ortega.

And yet, Aleyda, for all her anger and her frustration, is optimistic. Ortega’s government is implementing some of the region’s most progressive policies for the use of renewable energy, and poverty has fallen during his government. Aleyda is the fixer for the television programmes I am presenting in Managua, one of which is about the Sandinista philosophy. During a mock interview, where she played the role of one of the guests, I asked difficult questions and she was supposed to pretend that she was in the programme. “Don’t you think that the Sandinista ideology has no place in the modern world, in the times of globalisation and the technological revolution?” I pretended to ask. She got excited. “For as long as there is poverty and inequality, the Sandinista ideology will still be useful and needed”, she said, seriously, forgetting that she was only supposed to be pretending. She gave me a lesson about Sandino’s role in opposing the American occupation of her country, the Sandinista ideals that inspired a generation, her generation, her father’s humility. “I tried to convince my father, many times, that he should not be downhearted, that what he had done was worth doing”. Yes, he died disappointed and, yes, he never saw Daniel Ortega return to power but Aleyda is not ready to give up just yet. And this time, she smiled.

Under Ortega, Nicaragua has one of the most hard-line policies on therapeutic abortion in Latin America, neo-liberal policies keep the business sector happy and nothing moves without the permission of Rosario Murillo, the powerful wife of Daniel Ortega. From the silent wife of a revolutionary leader in the 1980s, she has become the power behind the throne. A minister, for instance, cannot give an interview to the media without getting authorisation from the Head of Government Communications, Rosario Murillo. No more collective decisions are taken by the FSLN leadership or by the community organisations that the Sandinistas created and cultivated after 1979. On Sunday, Ortega’s stepdaughter, who some years ago accused her stepfather of rape, gave an interview in which she talked about the hostility that her family faced for daring to expose Ortega.

And yet, Aleyda, for all her anger and her frustration, is optimistic. Ortega’s government is implementing some of the region’s most progressive policies for the use of renewable energy, and poverty has fallen during his government. Aleyda is the fixer for the television programmes I am presenting in Managua, one of which is about the Sandinista philosophy. During a mock interview, where she played the role of one of the guests, I asked difficult questions and she was supposed to pretend that she was in the programme. “Don’t you think that the Sandinista ideology has no place in the modern world, in the times of globalisation and the technological revolution?” I pretended to ask. She got excited. “For as long as there is poverty and inequality, the Sandinista ideology will still be useful and needed”, she said, seriously, forgetting that she was only supposed to be pretending. She gave me a lesson about Sandino’s role in opposing the American occupation of her country, the Sandinista ideals that inspired a generation, her generation, her father’s humility. “I tried to convince my father, many times, that he should not be downhearted, that what he had done was worth doing”. Yes, he died disappointed and, yes, he never saw Daniel Ortega return to power but Aleyda is not ready to give up just yet. And this time, she smiled.