The slow decline of the Brazilian Workers’ Party has emboldened the country’s growing right wing.

Speaking after her October reelection, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said that she didn’t think the country was divided. That might have been wishful thinking.

The 2014 campaign was the most bitter since Brazil returned to direct popular elections in 1989. Supporters of Aécio Neves, Rousseff’s opponent in the runoff election, expressed legitimate — albeit selective — indignation over the corruption scandals that have plagued the Workers’ Party (PT) in its twelve years in power. A new right-wing punditry has taken ownership of this outrage, launching tirades against the evils of big government and cynical leftist agents seeking to undermine traditional values — a discourse reminiscent of the American Tea Party.

This new Brazilian right, unlike the Tea Party, does not have a foundational moment in national history it can appropriate in order to oppose any kind of progressive politics — what Jill Lepore calls an anti-historical perspective. But its members still see even the smallest left initiative as a lethal threat to their vision of a good society.

They perceive themselves as engaged in a life-or-death struggle to protect Western civilization (narrowly understood as being sustained by the twin pillars of economic liberalism and cultural conservatism) against the specter of a scheming authoritarian left.

One of the leading figures in shaping this new right-wing discourse is Rodrigo Constantino, a blogger and columnist for Veja magazine. The morning after Rousseff’s reelection, Constantino posted on Facebook that people should find a copy of Atlas Shrugged. He followed with blog posts accusing Rousseff voters of being either ignorant or scoundrels, making it impossible to have a political discussion with them.

Possessing a truculent demeanor, Constantino likes to portray himself as speaking truth to power as Brazil speedily heads toward destination Havana. He enjoys pointing out the smallest signs of the country’s cultural transformation into an authoritarian communist state — from university conferences on Marxism to the use of red in the World Cup’s logo.

In addition to being a writer, Constantino is the president of the Instituto Liberal and a founding member of the Instituto Millenium, free-market organizations modeled after the Cato Institute. Other prominent members of the new Brazilian right include Olavo de Carvalho, a self-proclaimed philosopher, and Felipe Moura Brasil, who also has a Veja blog. These men have adroitly built a following in the digital age, starting blogs in the mid-2000s and promoting their views on Facebook, Twitter, and Orkut.

As they grew in popularity, the three men perfected an acerbic style fond of sarcastic diatribes (Constantino), ironic turns of phrases (Brasil), and homophobic profanity (Carvalho) not all that different from rightists like Ann Coulter, Andrew Breitbart, and Rush Limbaugh. The Brazilians are well versed in American conservative writers. Constantino, an ardent defender of the country’s elites, is fond of Thomas Sowell; Brasil, who sees himself as a cultural critic, has consistently drawn from Breitbart.com commentators, translating their articles and videos attacking the Left’s alleged slow march through the institutions; and Carvalho — who sees little to no difference between Barack Obama, Rousseff and Fidel Castro — gets his news from WorldNetDaily and Townhall.com.

The Brazilians are well versed in American conservative writers. Constantino, an ardent defender of the country’s elites, is fond of Thomas Sowell; Brasil, who sees himself as a cultural critic, has consistently drawn from Breitbart.com commentators, translating their articles and videos attacking the Left’s alleged slow march through the institutions; and Carvalho — who sees little to no difference between Barack Obama, Rousseff and Fidel Castro — gets his news from WorldNetDaily and Townhall.com.

Constantino, Brasil, and Carvalho have “tropicalized” some of the tropes that define contemporary American conservative discourse. They accuse any progressive organization of being a disingenuous militant operative for the PT, just as the Tea Party universalized its misgivings about ACORN to all forms of community organizing. They have also translated the myth of the American “welfare queen” into the lazy Bolsa Família beneficiary who abuses the system (even though the subsidies offered are hardly enough to allow a beneficiary to live as a “moocher”).

Even the Economist and the World Bank have praised the program, but Constantino and company interpret it as a political ploy by the PT to purchase votes. From there they construct a perverse political geography that sets “moochers” against “workers.” The largest concentration of families who have benefited from the program reside in the Northeast, a region historically ignored by the federal government in favor of the South and the Southeast — strongholds of the political and financial elites.

Following Rousseff’s victory, Constantino posted a colored-coded election map contrasting the states that each party took and bringing up the question of secession. Never mind that Neves failed to win his home state, Minas Gerais, which he governed for two terms and is in the Southeast, or that a gradated map shows that Rousseff’s popularity extended well into other regions.

But intellectual rigor has never been Constantino’s strong suit. His most recent book — which secured him the Veja position — is called Esquerda Caviar (a loose translation: “limousine liberals”). It is mainly an attack on the supposed hypocrisy of public figures like Chico Buarque and the recently deceased Oscar Niemeyer, who, according to Constantino, do not practice what they preach and are leftists only because it is trendy, since they still play by the rules of capitalism.

Esquerda Caviar resembles Jonah Goldberg’s Liberal Fascism, proclaiming to be thoughtful and well-researched yet still entertaining. Both books, however, have little intellectual merit. Historians of fascism dismissed Goldberg’s argument as being a simplistic political hit-job.

Robert Paxton, a preeminent scholar of Vichy France, criticized Goldberg for stereotyping liberals “to make them abstract, uniform, robotic.” Constantino follows the same procedure, presenting a homogeneous left (he manages to lump together names like Obama, Chomsky, Niemeyer, and Travolta) made up primarily of hypocrites who attack capitalism while gorging on its products.

Yet as the Brazilian anthropologist Rosana Pinheiro-Machado argues, the hypocrisy accusation is only sustained through a dishonest caricature of leftist thought. After all, for Marx himself the problem was not the bourgeoisie’s capacity to produce wealth, but the structures that promoted its unequal distribution through the exploitation of the proletariat.

And as if its spurious thesis were not enough, Esquerda Caviar also has factual errors, including quoting one of those grotesquely photoshopped images of a Wisconsin sign warning criminals that its citizens are armed (which was used to make a case for a liberalization of gun rights in Brazil).

At best, and this is probably what both authors hoped for, Goldberg and Constantino succeeded at creating catch terms that can be thrown around to avoid a thoughtful engagement with leftist critics. After all, there’s no point in arguing with fascists and hypocrites.

Like Constantino, Carvalho has also become more popular with the release of a book: O Mínimo Que Você Precisa Saber Para Não Ser Um Idiota (The Minimum You Need to Know to Not Be an Idiot). Most of Carvalho’s previous books were more esoteric and philosophical and thus had a limited impact, but O Mínimo is an edited collection of old, more accessible columns written by Carvalho for a gamut of publications. Brasil, who came up with the idea for the book, organized the essays into vast themes, such as “Youth,” “Socialism,” “Globalism,” and “Intelligentsia.”

As the reader makes her way through this comprehensive explanation of the contemporary world — Brasil compares Carvalho to Borges’s character in “The Aleph” who “sees everything simultaneously in reality” and is able to convey the image to his readers — she can learn how former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva managed to fool governments and media across the world into thinking he was a market-friendly socialist; how socialism, history’s biggest murderer, claimed the lives of more than 100 million people; how leftism is a psychological disorder; how the Rockefeller, Carnegie and Ford foundations have been funding anti-American and anti-capitalist research; and how Obama is part of the vast internationalist left-wing conspiracy to undermine American supremacy.

Brasil is one of Carvalho’s pupils and tends to regurgitate his tutor’s teachings on his blog or through pithy tweets. Carvalho has no academic training and is not cited by other philosophers, but this has not stopped him from starting a cultish online school, where for as low as $20 a month one can get a “General introduction to higher education in its totality.”

Carvalho’s students would argue that the education he offers tops that of institutions of higher learning, given that the latter are infiltrated by Marxists. His students see themselves as the guardians of conservative values and truth. Many are also enamored with the military, which they see as the last protector of Brazilian democracy, and have calling for it to intervene in Rousseff’s government — an absurdity they justify by reinterpreting the 1964 military coup as a preventive maneuver against a supposedly incoming Communist dictatorship.

Carvalho lives in Virgina. Yet the distance has not dampened his popularity. In fact, it has added to his messianic mystique. O Mínimo has become a bestseller through Brasil’s viral marketing, which portrays Carvalho as an exiled truth-teller — a twenty-first century, rightwing Victor Hugo. Carvalho also has the support of a number of b-list celebrities, including Lobão, a washed-up rocker who has been centrally involved in organizing the recent demonstrations calling for Rousseff’s impeachment — demonstrations that have also drawn a contingent calling for a return to the military dictatorship.

The protests have also served as a site for right-wing politicians to build up their credibility as a viable opposition. Eduardo Bolsonaro, a congressman for the Social Christian Party (PSC), gave a speech at a November protest in which, with a gun tucked into his waist, he praised the police for only beating up rowdy protestors (i.e. leftists).

Eduardo is the son of Jair Bolsonaro, a notably reactionary congressman for the Progressive Party (PP). Jair is a military man who celebrates the dictatorship years and enjoys going on tirades against human rights organizations. He favors the death penalty and the use of torture in police interrogations, and has made claims that if one of his sons had been gay he would have resolved the issue with a few spankings.

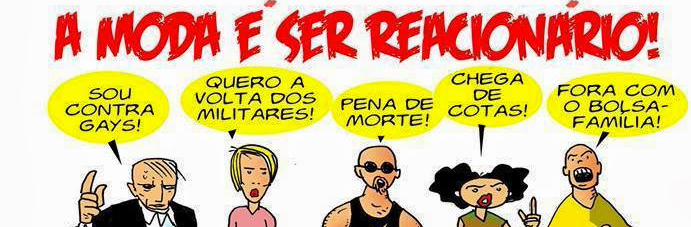

Cartoon: It’s fashionable to be reactionary! -I’m against gays; I want the military back in power; death penalty!; no more quotas; down with the ‘bolsa-familia’. Helping to build a worse Brazil.

Although they have their differences, Constantino, Carvalho, and Brasil all share a conspiratorial mind, believing that the Left in Brazil has created a hegemonic cultural environment through Gramscian tactics. The delusion consuming them is that a supranational organization, the Foro de São Paulo, is secretly succeeding in a communist takeover of Latin America. The Foro does exist, although it is better understood as a diverse network of leftist organization with views ranging from social democracy to communism that tries to articulate alternatives to neoliberalism — a sort of antithesis to Davos.

Constantino, Carvalho, and Brasil see the cultural sphere as the battlefield where the political war will be won, and they all seem to think that leftist are wining thanks to the battalions of “feminazis,” “gayzists,” and “racists” who have become increasingly vocal.

For the three white men, the rise of movements that oppose the sexism, homophobia, and racism that are still very much a feature of everyday life in Brazil is not the sign of a more open and participatory democracy, but the signal of a future dictatorship of political correctness. In an online world hungry for memes and strong positions articulated in small doses carrying a punch, this Manichaean vision has seduced a population disappointed with the ubiquitous corruption scandals of the last few decades.

With access to Veja, which has a weekly circulation of approximately one million, Constantino and Brasil now have a much wider audience than two years ago. Their diatribes are shared and liked on Facebook, the more quotable segments forwarded to Whatsapp groups. As the messages distance themselves from their source, they become disembodied idées reçus. And by amalgamating political corruption with a supposedly endemic social and cultural corruption, the new Brazilian right threatens much of the progress made on those two latter fronts over the last twelve years.

The reactionary vision articulated by these three culture warriors has arguably gained purchase because the Brazilian left has failed in its critique of the PT’s fall from grace. An ethical opposition party during the Fernando Henrique Cardoso years, the PT has become a governing party that’s not averse to using corruption in order to foster alliances and get things done.

There were glimpses of a decidedly critical leftist position when Luciana Genro, the presidential candidate for the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL), pointedly criticized the PT for failing to resist the yoke of finance capital after taking power. Meanwhile, Jean Wyllys, a PSOL congressman, has attracted a following among young people and used his status as a former reality TV star to speak against racial and sexual discrimination.

But both Genro and Wyllys are members of a small political party. They not only have limited exposure time during the campaign period, but they do not benefit from the aura of legitimacy that the lack of a party affiliation offers Constantino, et al.

The absence of critical radical publications has allowed Veja to claim the mantle of government watchdog (Carta Capital, the most prominent left-leaning magazine, has avoided hard hits against the PT). Veja claims impartiality but has always favored governments further to the right. Following Lula’s historic election in 2002, it found a new sense of purpose, reporting all the scandals and pseudo-scandals of the PT government with a missionary zeal.

Corruption has been a feature of the Rousseff administration, which is now dealing with a grafting scheme involving Brazil’s largest state-owned company, Petrobras. It was also present during Lula’s eight years in power, when another kickback scheme, the Mensalão, tainted his legacy.

But Neves’s party, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) has also had its fair share of scandals. There is strong evidence that in 1997 votes were bought in order to approve a constitutional amendment permitting reelection, which opened the path for Cardoso’s second term. (It is worth mentioning that independent inquiries into corruption and indictments have been undertaken with more zeal under Rousseff’s presidencies than under Cardoso’s).

The New York Times recently wrote that we might be seeing “the beginning of the end for the nation’s entrenched culture of impunity.” Still, the PT’s long run in power has given critics like Constantino plenty of ammunition to taint leftist causes writ large.

Two questions, then, remain to be answered. First, can a more aggressively responsible investigative journalism, something in the molds of ProPublica, emerge in Brazil to offer citizens a more nuanced analysis of the deeds and misdeeds of the political and financial classes? Second, can the Left find a voice that is both steadfastly critical of the PT’s transgressions and engaging as the new right?

The continuing construction of a more inclusive and just social democracy in Latin America’s biggest country and the world’s seventh largest economy may depend on the answers. Otherwise, reactionary voices will continue to acquire legitimacy, putting to test the hard-earned social advancements of the last twelve years.

The slow decline of the Brazilian Workers’ Party has emboldened the country’s growing right wing.

A December cover of the conservative Brazilian magazine Veja.

Speaking after her October reelection, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said that she didn’t think the country was divided. That might have been wishful thinking.

The 2014 campaign was the most bitter since Brazil returned to direct popular elections in 1989. Supporters of Aécio Neves, Rousseff’s opponent in the runoff election, expressed legitimate — albeit selective — indignation over the corruption scandals that have plagued the Workers’ Party (PT) in its twelve years in power. A new right-wing punditry has taken ownership of this outrage, launching tirades against the evils of big government and cynical leftist agents seeking to undermine traditional values — a discourse reminiscent of the American Tea Party.

This new Brazilian right, unlike the Tea Party, does not have a foundational moment in national history it can appropriate in order to oppose any kind of progressive politics — what Jill Lepore calls an anti-historical perspective. But its members still see even the smallest left initiative as a lethal threat to their vision of a good society.

They perceive themselves as engaged in a life-or-death struggle to protect Western civilization (narrowly understood as being sustained by the twin pillars of economic liberalism and cultural conservatism) against the specter of a scheming authoritarian left.

One of the leading figures in shaping this new right-wing discourse is Rodrigo Constantino, a blogger and columnist for Veja magazine. The morning after Rousseff’s reelection, Constantino posted on Facebook that people should find a copy of Atlas Shrugged. He followed with blog posts accusing Rousseff voters of being either ignorant or scoundrels, making it impossible to have a political discussion with them.

Possessing a truculent demeanor, Constantino likes to portray himself as speaking truth to power as Brazil speedily heads toward destination Havana. He enjoys pointing out the smallest signs of the country’s cultural transformation into an authoritarian communist state — from university conferences on Marxism to the use of red in the World Cup’s logo.

In addition to being a writer, Constantino is the president of the Instituto Liberal and a founding member of the Instituto Millenium, free-market organizations modeled after the Cato Institute. Other prominent members of the new Brazilian right include Olavo de Carvalho, a self-proclaimed philosopher, and Felipe Moura Brasil, who also has a Veja blog. These men have adroitly built a following in the digital age, starting blogs in the mid-2000s and promoting their views on Facebook, Twitter, and Orkut.

As they grew in popularity, the three men perfected an acerbic style fond of sarcastic diatribes (Constantino), ironic turns of phrases (Brasil), and homophobic profanity (Carvalho) not all that different from rightists like Ann Coulter, Andrew Breitbart, and Rush Limbaugh.

The Brazilians are well versed in American conservative writers. Constantino, an ardent defender of the country’s elites, is fond of Thomas Sowell; Brasil, who sees himself as a cultural critic, has consistently drawn from Breitbart.com commentators, translating their articles and videos attacking the Left’s alleged slow march through the institutions; and Carvalho — who sees little to no difference between Barack Obama, Rousseff and Fidel Castro — gets his news from WorldNetDaily and Townhall.com.

Constantino, Brasil, and Carvalho have “tropicalized” some of the tropes that define contemporary American conservative discourse. They accuse any progressive organization of being a disingenuous militant operative for the PT, just as the Tea Party universalized its misgivings about ACORN to all forms of community organizing. They have also translated the myth of the American “welfare queen” into the lazy Bolsa Família beneficiary who abuses the system (even though the subsidies offered are hardly enough to allow a beneficiary to live as a “moocher”).

Even the Economist and the World Bank have praised the program, but Constantino and company interpret it as a political ploy by the PT to purchase votes. From there they construct a perverse political geography that sets “moochers” against “workers.” The largest concentration of families who have benefited from the program reside in the Northeast, a region historically ignored by the federal government in favor of the South and the Southeast — strongholds of the political and financial elites.

Following Rousseff’s victory, Constantino posted a colored-coded election map contrasting the states that each party took and bringing up the question of secession. Never mind that Neves failed to win his home state, Minas Gerais, which he governed for two terms and is in the Southeast, or that a gradated map shows that Rousseff’s popularity extended well into other regions.

But intellectual rigor has never been Constantino’s strong suit. His most recent book — which secured him the Veja position — is called Esquerda Caviar (a loose translation: “limousine liberals”). It is mainly an attack on the supposed hypocrisy of public figures like Chico Buarque and the recently deceased Oscar Niemeyer, who, according to Constantino, do not practice what they preach and are leftists only because it is trendy, since they still play by the rules of capitalism.

Esquerda Caviar resembles Jonah Goldberg’s Liberal Fascism, proclaiming to be thoughtful and well-researched yet still entertaining. Both books, however, have little intellectual merit. Historians of fascism dismissed Goldberg’s argument as being a simplistic political hit-job.

Robert Paxton, a preeminent scholar of Vichy France, criticized Goldberg for stereotyping liberals “to make them abstract, uniform, robotic.” Constantino follows the same procedure, presenting a homogeneous left (he manages to lump together names like Obama, Chomsky, Niemeyer, and Travolta) made up primarily of hypocrites who attack capitalism while gorging on its products.

Yet as the Brazilian anthropologist Rosana Pinheiro-Machado argues, the hypocrisy accusation is only sustained through a dishonest caricature of leftist thought. After all, for Marx himself the problem was not the bourgeoisie’s capacity to produce wealth, but the structures that promoted its unequal distribution through the exploitation of the proletariat.

And as if its spurious thesis were not enough, Esquerda Caviar also has factual errors, including quoting one of those grotesquely photoshopped images of a Wisconsin sign warning criminals that its citizens are armed (which was used to make a case for a liberalization of gun rights in Brazil).

At best, and this is probably what both authors hoped for, Goldberg and Constantino succeeded at creating catch terms that can be thrown around to avoid a thoughtful engagement with leftist critics. After all, there’s no point in arguing with fascists and hypocrites.

Like Constantino, Carvalho has also become more popular with the release of a book: O Mínimo Que Você Precisa Saber Para Não Ser Um Idiota (The Minimum You Need to Know to Not Be an Idiot). Most of Carvalho’s previous books were more esoteric and philosophical and thus had a limited impact, but O Mínimo is an edited collection of old, more accessible columns written by Carvalho for a gamut of publications. Brasil, who came up with the idea for the book, organized the essays into vast themes, such as “Youth,” “Socialism,” “Globalism,” and “Intelligentsia.”

As the reader makes her way through this comprehensive explanation of the contemporary world — Brasil compares Carvalho to Borges’s character in “The Aleph” who “sees everything simultaneously in reality” and is able to convey the image to his readers — she can learn how former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva managed to fool governments and media across the world into thinking he was a market-friendly socialist; how socialism, history’s biggest murderer, claimed the lives of more than 100 million people; how leftism is a psychological disorder; how the Rockefeller, Carnegie and Ford foundations have been funding anti-American and anti-capitalist research; and how Obama is part of the vast internationalist left-wing conspiracy to undermine American supremacy.

Brasil is one of Carvalho’s pupils and tends to regurgitate his tutor’s teachings on his blog or through pithy tweets. Carvalho has no academic training and is not cited by other philosophers, but this has not stopped him from starting a cultish online school, where for as low as $20 a month one can get a “General introduction to higher education in its totality.”

Carvalho’s students would argue that the education he offers tops that of institutions of higher learning, given that the latter are infiltrated by Marxists. His students see themselves as the guardians of conservative values and truth. Many are also enamored with the military, which they see as the last protector of Brazilian democracy, and have calling for it to intervene in Rousseff’s government — an absurdity they justify by reinterpreting the 1964 military coup as a preventive maneuver against a supposedly incoming Communist dictatorship.

Carvalho lives in Virgina. Yet the distance has not dampened his popularity. In fact, it has added to his messianic mystique. O Mínimo has become a bestseller through Brasil’s viral marketing, which portrays Carvalho as an exiled truth-teller — a twenty-first century, rightwing Victor Hugo. Carvalho also has the support of a number of b-list celebrities, including Lobão, a washed-up rocker who has been centrally involved in organizing the recent demonstrations calling for Rousseff’s impeachment — demonstrations that have also drawn a contingent calling for a return to the military dictatorship.

The protests have also served as a site for right-wing politicians to build up their credibility as a viable opposition. Eduardo Bolsonaro, a congressman for the Social Christian Party (PSC), gave a speech at a November protest in which, with a gun tucked into his waist, he praised the police for only beating up rowdy protestors (i.e. leftists).

Eduardo is the son of Jair Bolsonaro, a notably reactionary congressman for the Progressive Party (PP). Jair is a military man who celebrates the dictatorship years and enjoys going on tirades against human rights organizations. He favors the death penalty and the use of torture in police interrogations, and has made claims that if one of his sons had been gay he would have resolved the issue with a few spankings.

Although they have their differences, Constantino, Carvalho, and Brasil all share a conspiratorial mind, believing that the Left in Brazil has created a hegemonic cultural environment through Gramscian tactics. The delusion consuming them is that a supranational organization, the Foro de São Paulo, is secretly succeeding in a communist takeover of Latin America. The Foro does exist, although it is better understood as a diverse network of leftist organization with views ranging from social democracy to communism that tries to articulate alternatives to neoliberalism — a sort of antithesis to Davos.

Constantino, Carvalho, and Brasil see the cultural sphere as the battlefield where the political war will be won, and they all seem to think that leftist are wining thanks to the battalions of “feminazis,” “gayzists,” and “racists” who have become increasingly vocal.

For the three white men, the rise of movements that oppose the sexism, homophobia, and racism that are still very much a feature of everyday life in Brazil is not the sign of a more open and participatory democracy, but the signal of a future dictatorship of political correctness. In an online world hungry for memes and strong positions articulated in small doses carrying a punch, this Manichaean vision has seduced a population disappointed with the ubiquitous corruption scandals of the last few decades.

With access to Veja, which has a weekly circulation of approximately one million, Constantino and Brasil now have a much wider audience than two years ago. Their diatribes are shared and liked on Facebook, the more quotable segments forwarded to Whatsapp groups. As the messages distance themselves from their source, they become disembodied idées reçus. And by amalgamating political corruption with a supposedly endemic social and cultural corruption, the new Brazilian right threatens much of the progress made on those two latter fronts over the last twelve years.

The reactionary vision articulated by these three culture warriors has arguably gained purchase because the Brazilian left has failed in its critique of the PT’s fall from grace. An ethical opposition party during the Fernando Henrique Cardoso years, the PT has become a governing party that’s not averse to using corruption in order to foster alliances and get things done.

There were glimpses of a decidedly critical leftist position when Luciana Genro, the presidential candidate for the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL), pointedly criticized the PT for failing to resist the yoke of finance capital after taking power. Meanwhile, Jean Wyllys, a PSOL congressman, has attracted a following among young people and used his status as a former reality TV star to speak against racial and sexual discrimination.

But both Genro and Wyllys are members of a small political party. They not only have limited exposure time during the campaign period, but they do not benefit from the aura of legitimacy that the lack of a party affiliation offers Constantino, et al.

The absence of critical radical publications has allowed Veja to claim the mantle of government watchdog (Carta Capital, the most prominent left-leaning magazine, has avoided hard hits against the PT). Veja claims impartiality but has always favored governments further to the right. Following Lula’s historic election in 2002, it found a new sense of purpose, reporting all the scandals and pseudo-scandals of the PT government with a missionary zeal.

Corruption has been a feature of the Rousseff administration, which is now dealing with a grafting scheme involving Brazil’s largest state-owned company, Petrobras. It was also present during Lula’s eight years in power, when another kickback scheme, the Mensalão, tainted his legacy.

But Neves’s party, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) has also had its fair share of scandals. There is strong evidence that in 1997 votes were bought in order to approve a constitutional amendment permitting reelection, which opened the path for Cardoso’s second term. (It is worth mentioning that independent inquiries into corruption and indictments have been undertaken with more zeal under Rousseff’s presidencies than under Cardoso’s).

The New York Times recently wrote that we might be seeing “the beginning of the end for the nation’s entrenched culture of impunity.” Still, the PT’s long run in power has given critics like Constantino plenty of ammunition to taint leftist causes writ large.

Two questions, then, remain to be answered. First, can a more aggressively responsible investigative journalism, something in the molds of ProPublica, emerge in Brazil to offer citizens a more nuanced analysis of the deeds and misdeeds of the political and financial classes? Second, can the Left find a voice that is both steadfastly critical of the PT’s transgressions and engaging as the new right?

The continuing construction of a more inclusive and just social democracy in Latin America’s biggest country and the world’s seventh largest economy may depend on the answers. Otherwise, reactionary voices will continue to acquire legitimacy, putting to test the hard-earned social advancements of the last twelve years.