As part of their Other Modernisms, Other Futures: Global Art Cinema 1960-80 series, the Barbican Centre will screen two films from the New Latin American Cinema movement.

They state: ‘The 1960s and 70s were a period of revolution, anti-imperialist struggle, and nation-building. Across the world, modernist filmmakers thought of their films as interventions in contemporary social, political or ideological debates, as a contribution towards new possibilities, new futures and new worlds.’

Latin America was no exception, with attempts to stir revolutionary sentiment throughout the New Latin American Cinema Movement in Cuba, Bolivia, Colombia, Brazil and across the continent. Much of this filmmaking strived to create new styles and a cinematic language that reflected indigenous, national and even pan-Latin American values, instead of following European methods and emulating Hollywood tropes.

Two such films reflecting the anxieties of this period and the hopes of New Latin American Cinema: De cierta manera / One Way Or Another (Sara Gómez, 1974) and Yawar Mallku / Blood of the Condor (Jorge Sanjinés, 1969) will be screened at the beginning of March, alongside modernist films from Iran, India, Senegal/France and the USSR.

Blood of the Condor

Jorge Sanjinés’ Yawar Mallku was a political call to arms, developed alongside his revolutionary cinematic collective Grupo Ukumao, for peasant and working-class audiences in the Andean highlands of Bolivia. It depicts the North American Peace Corps imposing capitalist ideology through medicinal and psychological violence, as indigenous men and women are sterilised against their will in medical centres set up in indigenous communities near La Paz. When Ignacio, a community leader finds out, he takes revenge.

Yawar Mallku was one of the first films to feature Quechua symbolism and language in its title. As the predominant spoken language of the film, Quechua or runa simi – ‘language of the people’- symbolises the social collective as protagonist of the film rather than an individual hero, as in the Hollywood prototype.

It was seen by more Bolivians than any other domestic or foreign film at the time and managed to achieve political change, as it led directly to the Peace Corps’ exit from the country in 1971.

‘Each country has to find their language’ Sanjinés has said many times, and Ukamau’s principal concern was to authentically capture the subjectivity of the Andean indigenous peoples and to invest a new morality into the narrative of U.S. relations in Bolivia and beyond.

One Way or Another

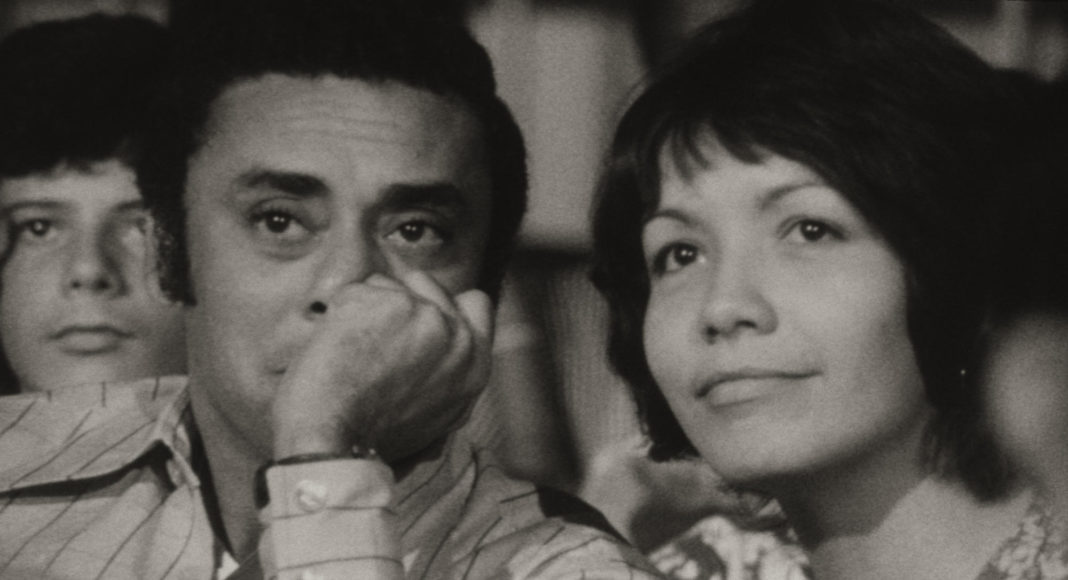

De cierta manera, the first Cuban feature directed by a woman, is a more quotidian, analytical love story, which, through narrative and ethnographic-style documentary filming, deals insightfully with the lasting forms of colonialism in 1970s Cuba and citizens’ endeavours to understand and live by socialist values.

Gómez shows the process of the Revolution as an ongoing debate and struggle away from unjust patterns of behaviour and closer to an ideal of socialist organisation, work, and interpersonal relations. But she examines this ideal, analysing the codes of machismo which shaped and still influence Cuban male behaviour and including documentary footage of life for Cuba’s working classes in the ‘70s and specifically the Five Grey Years – in the factory, the home and the streets.

This film is insightful, spirited and unflinching in its treatment of race, class and gender inequality in outer Havana, joining the shifting dots between Cuba’s violently colonialist past and its uncertain future. The narrative is factual, almost ethnographic, opening a window to the tensions within a new socialist society and constantly questioning the characters in terms of their historical constructs and contradictions.

Check out the Other Modernisms, Other Futures: Global Art Cinema 1960-80 season at the Barbican here.