As director Kleber Mendonça illustrated in Bacurau, Pablo Larraín in El Club or Patricio Guzmán in Nostalgia por la luz, genre is an effective tool for depicting institutionalised racism, collective resistance and state violence. Choosing horror as the carrier for La Llorona, a film about violence and reparation, Guatemalan director Jayro Bustamante proves that nuanced, chilling compositions upstage cheap shock and gore. The horror slowly creeps into Guatemala’s Oscar contender, which begins as a political thriller and ends as a chillingly cinematic revenge-horror film.

Enrique Monteverde, a detached ex-dictator, is on trial for genocide. Pampered and protected by his immediate family and employees, but haunted by La Llorona at night, he is suffering what they believe to be Alzheimer’s-related delusions. Although he’s found guilty at trial, the verdict is overturned, which sparks outrage from the crowds of justice-seekers who begin to surround his house en masse to protest the ruling day-in, day-out. The Monteverde family, in lockdown, slowly loses control. With the help of a new maid, Alma, they must face up to the horrors they’ve continued to deny for decades – by recognising the dead.

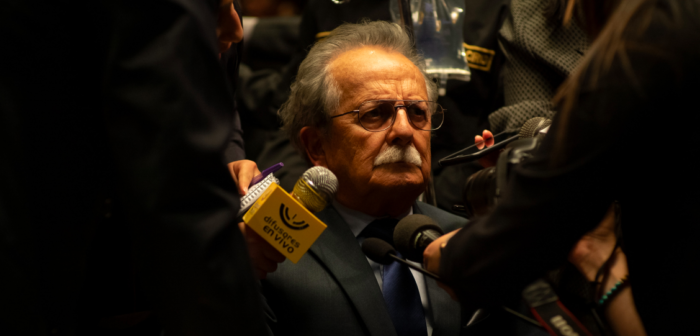

Enrique is clearly based on General Efrain Ríos Montt, who ruled as a dictator during some of Guatemala’s bloodiest years in the 1980s, with the support of the US and Israeli military. He was finally convicted of genocidal war crimes in 2013, only for the Court to overturn his conviction 10 days later on account of his old age and ill health.

The Truth Commissions of the ‘90s found that most crimes of the 36-year civil war were committed between 1980 and 1983; that 79% of all human rights violations were committed by the military; and that 83% of the victims were Mayan. In a postcolonial effort to atone, La Llorona twists the well known Mesoamerican folktale of the wailing ghost who mourns her drowned children, to serve retribution to those continually denied justice.

Through the central family, director Jayro Bustamante comments on a generational progression towards reconciliation in Guatemala, where violence ravaged much of the country for over 36 years. The dictator and his wife Carmen are disconnected, cold, repressed – they must be respectively condemned or possessed in order to confront the horror they have sanctioned. Their naive daughter Sabrina appears to be awakening to the truth, caught between complicity and rebellion – she wants answers but has inherited her parents’ enduring silence. “You mustn’t allow yourself to think like that” she’s told, “Whose side are you on?”

Sabrina’s questions prevail, yet they are robbed of their impact by the ridiculous setting. She contemplates whilst sunbathing with her mother on their manicured lawn, stubbornly ignoring the cacophony of the protests. Sara, Enrique’s fatherless granddaughter, however, marks a new chapter. She connects the past to the present, announces the truth and is able to begin reconciliation.

Although the upper-class Monteverde family are the central focus of the plot, Mayan symbolism and language imbue the film with meaning. The script includes lines in Mayan-Ixil, Mayan-Kaqchikel and Spanish, painting a realistic soundscape of a multilingual country. Bustamante’s previous Oscar-contending film Ixcanul (2015) is believed to be the first feature film in Kaqchikel language.

In a powerful scene inspired in the Sepur Zarco case – in which a group of women wearing embroidered t’zute veils for modesty shared tragic testimonies against the soldiers who murdered their children and held them as sex slaves – an elderly Mayan woman gives her testimony in a translucent, ornamental veil. The camera zooms out to show a striking congregation of women supporting her, all wearing the veil. After giving her testimony she removes the t’zute and declares: “if we are not ashamed of telling what we lived through, we hope you are not ashamed of doing justice.”

Water, in some form, is the haunting backbone of the age-old legend of La Llorona. In Bustamante’s production, it inundates the family imaginary, mirroring the suffocation they feel from the popular protests taking place outside their gated home. Water plagues Enrique’s visions, perhaps recalling the pain of the 350 massacred on the Río Pixcaya; the fishermen who found human limbs in their nets rather than food; the bodies of disappeared prisoners thrown out of Guatemalan Air Force planes into the Pacific Ocean; the people buried alive in wells in Las Dos Eres.

Tropes are borrowed and held up to scrutiny, like the devotion of the family’s maid who’s been with them close to her whole life. In the final scene Valeriana, in a Mayan blessing, prays for herself and the family she serves, asking for the innocent to be spared. In doing so, she holds up a mirror for society to question the devotion expected of servants, whilst forcing the audience to question everyone’s complicity.

Another cliché is Enrique’s compulsive sexual interest in the newly employed younger maid, Alma. “He’s always liked women”, his wife tells their daughter with disgust – especially indigenous girls. An erotics of power is paramount to the horrors of the genocide and sexual violence was weaponised throughout. Carmen bans Alma from wearing her “tight” uniform, perhaps aiming to strip her of a layer of sexual accessibility by removing the costume of servitude and replacing it with the indigenous dress she views with disdain. In her traje, however, Alma is elusive and empowered.

To aid Bustamante in telling these stories, he consulted a focus group made up of indigenous community leaders and people who continue to search for the remains of the disappeared and for children of the victims. One of the most active members of this group, he told Carlos Aguilar, was Rigoberta Menchú, the Nobel Prize-winning activist and author. You can even spot Menchú in the trial scene, alongside her family sitting in exactly the same spot as in the real trial of Efraín Ríos Montt.

The 1995 Catholic Church-sponsored truth commission (the Interdiocesan Project for the Recovery of Historical Memory (REMHI)) was written by and for Guatemalans and served more as a collection of testimonies than the dry collection of statistics compiled by the international Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH). So, too, La Llorona contributes towards a sense of justice through the truth-telling, cathartic process of filmmaking, and through watching and screening the film itself.

The story’s denouement offers its own form of ultimate justice, in a hair-raising, spiritual scene of retribution in which neither Christian God nor corrupt government can save the general from vengeful spirits.

You can watch La Llorona on Amazon Prime’s Shudder service and see LAB’s photo-essay on the Ríos Montt genocide trial here.