On 20 November, a group of four women known as Las Tesis from Valparaíso, Chile, unknowingly started what would become an international phenomenon in the global struggle against sexism and gender-based violence: they performed the anti-machista anthem and routine ‘Un Violador en tu Camino’ for the first time.

The group hoped that the song would spread feminist theory in a simple way to people who would not otherwise have the opportunity to read or analyse it. Its hard-hitting lyrics address ongoing violence against women, rape, and femicide, and the persistence of machismo at domestic, systemic, and state levels in Chile.

It is estimated that one in three women suffer or have suffered sexual violence in Chile. In 2016 alone, there were over 15,000 reports of sexual violence, while it is estimated that for every report made, six incidents of abuse go unreported.

Yet gender-based violence and discrimination persists without effective measures of prevention and often with impunity.

In the context of the ongoing protests in the country, triggered by an increase in the capital’s metro fares, but which have gone on to demand the overhaul of systematic inequalities and abuses, Chilean feminists are determined that any new system brings justice for them too, after years of seeing women’s concerns being relegated to second place.

La Revolución será feminista o no será

(Either the Revolution will be feminist, or it will not be a revolution)

Since the mass protests swept Chile, various feminist groups that each have their own specific aims, such as Afrochilenas, indigenous women’s groups and groups that work on abortion, have come together.

AFEMIC, the feminist collective in Arica, a city in the far north of Chile, is one of these. It aims to bring together different branches of feminism and self-identifying women in a space where they can develop their feminist thinking, hold activities, and support each other.

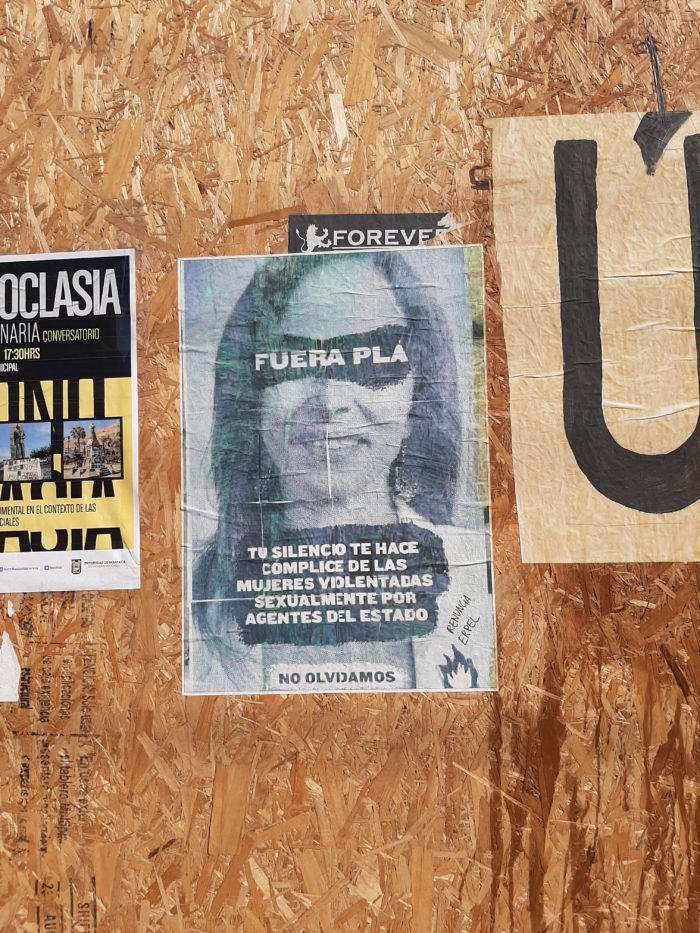

They have also declared themselves ‘actores de choque’ (shock troops). Along with their performances of ‘Un Violador en tu Camino’, AFEMIC, for example, have put up uncompromising posters around the city to highlight the issue of femicide and impunity for the crime. The aim is to make people uncomfortable and force them to think critically about their reality, and the posters do just that.

However, the women’s activism brings with it a heightened concern for security that all women face on a daily basis. They are particularly concerned about the police. Their painting of police buildings and posting flyers is, in the words of AFEMIC’s representative, an attack – not a violent, but a symbolic attack, just as ‘Un Violador en tu Camino’ is an attack on the judiciary, on the government, and on men who have not been prosecuted for their violence.

‘El Estado opresor es un macho violador

(The oppressor state is a rapist male])

‘Son los pacos (it’s the police),

los jueces (the judges),

el Estado (the State),

el president (the president).’

Minister for Women and Gender Equality, Isabel Plá, praised the impact of ‘Un Violador en tu Camino’ and her admiration for the women who as a result came forward to denounce historical sexual violence. Plá used the opportunity for a propaganda stunt, vaguely speaking of the reforms that her ministry is undertaking to reduce impunity, to strengthen protection measures, and to improve preventative and protection programs and institutions.

However, just as the Chilean political elite more generally are being condemned for their empty words, Plá was met with heavy criticism for the lack of action until now, for not having spoken on this topic during the protests until it received international attention, and for having remained silent about the accusations of the rape and assaults on Chile Despierta protestors by security forces.

Her critics also highlighted the irony of her praise, in contrast to the song’s denunciations of the complicity of state bodies and the judicial system in the practice of machismo, which grant impunity to the culprits of femicide and gender-based violence while women are told to stay inside for their safety.

The Comunicado Feminista, signed by 35 Chilean feminist and women’s groups for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, demanded that Plá step down because of her lack of action and failure to react to the various allegations of political sexual violence. She has become an accomplice of state machismo, they say, rather than an ally in the cause for gender equality.

‘Y la culpa no era mía, ni dónde estaba ni cómo vestía.’

(It wasn’t me that was to blame, nor where I was, nor how I dressed)

Nevertheless, the internationalisation of ‘Un Violador en tu Camino’, according to a representative from AFEMIC, has helped to prioritise feminism in Chile; it can no longer be put in second place because it has opened the door between Chilean and international feminism.

The anthem has been repeated across Chile and the world, including in Buenos Aires, Bogotá, France, Germany, the UK and India to name but a few. According to the representative of the AFEMIC, victim-blaming and discrimination simply for being a woman is a universal experience to which all who identify as women can relate.

Nevertheless, the dance-chant remains specific to the Chilean situation. The blindfold that the participants wear, for example, as well as representing the invisible side to gender-based violence, is a reminder of the torture practised during the Pinochet dictatorship.

The demands of the various feminist groups expressed through their manifestos are specific to Chile too, while their local base allows them to target regional issues. AFEMIC focus on the intersectionality of feminism and land, such as the demand for a territorio plurinacional – the demand for Chile to be defined as a land of many peoples – and the struggles of indigenous groups in the north of the country over mining and water.

But there are clear and powerful demands being made at both the local and national level. For example, the manifestos denounce the ‘conscientious objector’ clause added in 2018 to the 2017 law which legalized abortion in certain cases. This clause allows medical professionals to refuse to carry out the wishes of the patient, thus placing the control of women’s bodies back in the hands of someone else.

The groups also call for an end to state violence and the patriarchal state, which allowed the peace agreement and decisions made to calm the recent social explosion to be made predominantly by white men behind closed doors. They insist upon the fundamental requirement that the resolution to the protests in the country needs to include the whole society, including the feminist voice.

At present, there remains much uncertainty over what the future holds for Chile. Various groups from different sectors of the population are making their demands for a more just society. While almost every demand has been made at some time in the past, usually meeting with scant success, this time, as far as the Chile’s feminists are concerned, they will not back down.

Emily Gregg is a LAB correspondent and author, now based in Arica, Chile. She wrote The Student Revolution chapter in LAB’s book Voices of Latin America (2019).