In the example above, the receptionist followed the law, while the smoking prosecutor broke it shamelessly, with the body language of someone completely unmoved by the outrage caused. Moreover, she broke the law while being a professional in charge of enforcing it. For the receptionist, the choice to retreat rather than get into trouble was obvious – she was his boss. My reaction was obvious too. My work in that small town relied to a great extent on social relationships, in a place where everybody knows everyone else. Anyway, since she was a prosecutor, to whom could I complain?

That happened in 2013 – a time of street protests in Brazil. As vast sums were being lavished on World Cup and Olympic Games prestige projects, millions of Brazilians took to the streets in protest against corruption and poor public services. It is always easier, when so many were taking action, to ignore those who remain silent. All over Brazil, however, there were also people who neither demonstrated nor complained about abuses of power.

Once again, during the 2018 Presidential elections, millions of Brazilians are using their social networks to voice in favour of or, more commonly, against certain candidates. #eleNao, #PTnao are hashtags easy to find in Facebook timelines and on Twitter. But with the clamour of all these public expressions in front of us, how can we remember the millions of Brazilians who are not voicing their views, or are doing so with great fear of repercussions?

In the example above, the receptionist followed the law, while the smoking prosecutor broke it shamelessly, with the body language of someone completely unmoved by the outrage caused. Moreover, she broke the law while being a professional in charge of enforcing it. For the receptionist, the choice to retreat rather than get into trouble was obvious – she was his boss. My reaction was obvious too. My work in that small town relied to a great extent on social relationships, in a place where everybody knows everyone else. Anyway, since she was a prosecutor, to whom could I complain?

That happened in 2013 – a time of street protests in Brazil. As vast sums were being lavished on World Cup and Olympic Games prestige projects, millions of Brazilians took to the streets in protest against corruption and poor public services. It is always easier, when so many were taking action, to ignore those who remain silent. All over Brazil, however, there were also people who neither demonstrated nor complained about abuses of power.

Once again, during the 2018 Presidential elections, millions of Brazilians are using their social networks to voice in favour of or, more commonly, against certain candidates. #eleNao, #PTnao are hashtags easy to find in Facebook timelines and on Twitter. But with the clamour of all these public expressions in front of us, how can we remember the millions of Brazilians who are not voicing their views, or are doing so with great fear of repercussions?

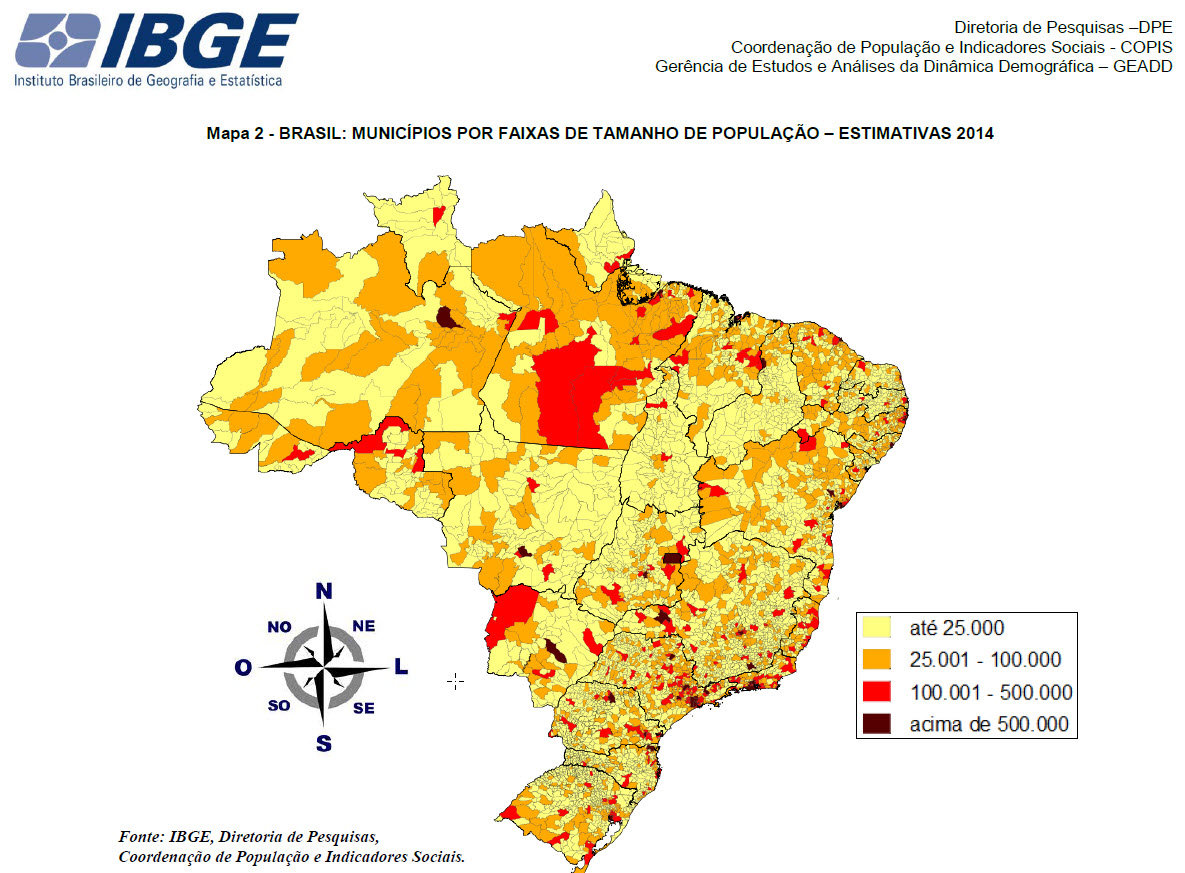

Brazil has 5,570 municipalities, of which 4,903 have less than 50.000 inhabitants (IBGE 2018). For those who live in these small cities, a system of friendship shapes the informal economy. People rely on friends for shopping, house construction, and job seeking. In the supermarket, for example, residents may have a tab for their shopping, a bill to be paid ‘when things get better’, ‘because someone who has a “name”, someone who has friends has everything’, as my informants used to say. To make local enemies may compromise future employment and economic favours. There is also a domino effect in small cities, where the actions of family members, friends, and neighbours reflect badly on those around them.

Brazil has 5,570 municipalities, of which 4,903 have less than 50.000 inhabitants (IBGE 2018). For those who live in these small cities, a system of friendship shapes the informal economy. People rely on friends for shopping, house construction, and job seeking. In the supermarket, for example, residents may have a tab for their shopping, a bill to be paid ‘when things get better’, ‘because someone who has a “name”, someone who has friends has everything’, as my informants used to say. To make local enemies may compromise future employment and economic favours. There is also a domino effect in small cities, where the actions of family members, friends, and neighbours reflect badly on those around them.

‘Ir pra geladeira’

Even those who have a career in the public sector and are part of a formal economy know what it means to ‘go into the freezer’. Ir pra geladeira means to be removed from core activities, to be precluded from meaningful decisions, to be excluded from management. Ir pra geladeira means to have upset those in power.

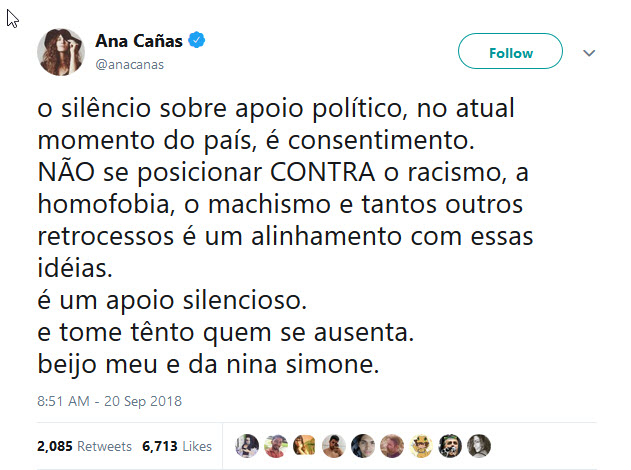

“Silence about your political position, in the present situation in the country, is consent. Not to take a stand against racism, homophobia, machismo and so many other retrograde positions is to align yourself with them. It is to give silent support. Take note of those who are absent. A kiss from me and from Nina Simone.”

— In Brazil’s febrile political atmosphere, even silence now stands accused! Perhaps Cañas overlooks the other motives of so many people – fear, and the need to survive. Not everyone has an equal voice, the same freedom to speak or the same impact when they do speak.

Andreza de Souza Santos is Director of the Brazilian Studies Centre and a lecturer at the Latin American Centre, University of Oxford. A political scientist and social anthropologist, she is interested in participatory politics and grass-roots activism in cities. Her book The Politics of Urban Cultural Heritage: Contestations and Participation in Brazil will be published in 2019