The death in Buenos Aires of the public prosecutor Alberto Nisman remains a complete mystery, despite constant speculation and guesswork in Argentina and elsewhere.

Nisman died from a gunshot wound one day before he was due to present a 289-page report accusing the Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Foreign Minister Hector Timerman of colluding with the Iranian government to cover up their responsibility for the notorious 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish centre in Buenos Aires which left 85 dead.

Nisman died from a gunshot wound one day before he was due to present a 289-page report accusing the Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Foreign Minister Hector Timerman of colluding with the Iranian government to cover up their responsibility for the notorious 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish centre in Buenos Aires which left 85 dead.

President Fernández at first called Nisman’s death a suicide, but later said she no longer believed it was suicide and accused ‘rogue elements’ in the national security services of his murder.

Kirchner proposes radical shake-up of intelligence services

She followed this up with proposals to completely overhaul Argentina’s intelligence services. These are to be debated in February 2015 in both chambers of the national Congress.

The main point of the reforms is to introduce greater oversight by Congress and the attorney general over Argentina’s intelligence services, which are often accused of acting outside democratic constraints. Some of the services’ 2,000 personnel are accused of taking part in the ‘dirty war’ unleashed by the military dictatorship in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Under the new proposals, the director and deputy director of the proposed Federal Intelligence Agency would be appointed by the Senate rather than the executive. Wiretaps and other sensitive use of secret material will need authorisation from the attorney-general.

Who killed Alberto Nisman?

Meanwhile, the search goes on for a judge to evaluate the accusations against Cristina Fernández contained in Nisman’s dossier.

He had been in charge of investigations into the AMIA bombing since 2006, when he replaced Juan José Galeano, who was himself dismissed for allegedly taking a bribe from a witness.

The AMIA massacre occurred when a bomb was placed in a van outside the Jewish social centre on Calle Pasteur early one morning in July 1994. Eighty-five people were killed inside the building and in the street outside, in a predominantly Jewish area of the Argentine capital.

The AMIA massacre occurred when a bomb was placed in a van outside the Jewish social centre on Calle Pasteur early one morning in July 1994. Eighty-five people were killed inside the building and in the street outside, in a predominantly Jewish area of the Argentine capital.

No-one was arrested at the time of the blast, and the only person to face charges was a former police officer, accused of supplying the bombers with the van used in the attack.

Family members of the victims accused the then government of Carlos Menem of complicity in the attack, claiming the authorities allowed a Hezbollah group to enter and leave the country in return for receiving multi-million dollar payments. The Hezbollah group, they alleged, was paid by the government in Tehran.

Iran has always strenuously denied any involvement in the AMIA atrocity.

Prominent political commentator Horacio Verbitsky has long sustained that the specific accusation against Iran was concocted by the US and Israel, anxious at the time to demonise Tehran, and ignored the probable role of Syria, where President Assad (father of Bashar al-Assad) was, at the time, engaged in a rapprochement with the US and collaborations over the civil war in Lebanon and the first Gulf War against Iraq.

A reading of extracts from Nisman’s report (whose authenticity has also been questioned) reveal language of ringing denunciation more typical of a political speech than a judicial report.

The role of Iran

The blast at AMIA followed one two years earlier at the Israeli embassy, also in downtown Buenos Aires, in which 29 people were killed. Nobody has faced charges for that attack either.

Alberto Nisman was convinced from early on that Iran was responsible for the AMIA bombing.

In 2007, he gave a vivid description of his reconstruction of the attack:

‘The attack took place at nine fifty-three on the morning of July the 18th 1994. It was a suicide car bomb, in a Renault Trafic driven by a Lebanese militant, who was a member of Hezbollah. He drove down the street, and when he got to the AMIA building, he swung the car to the right and crashed it into the entrance gate.’

He was equally adamant that the decision to bomb a target in Argentina was taken at the very highest levels of the Iranian government.

He said he had proof that the then President Ali Akhbar Rafsanjani and foreign minister Velayati were present at a meeting of Iran’s Security Council in the town of Mashad in August 1993.

However, this ‘proof’ leans heavily on the testimony of Abolghassem Mesbahi, a defector who was formerly a high-level Iranian official. Such testimony is often questionable.

Oil and nuclear fuel

In his investigation, Nisman claimed to have traced the plot to attack a Jewish target in Argentina back to the Argentine government’s decision to first suspend and then cancel contracts it had with Iran to supply it with nuclear material for its nuclear power plants.

Nisman said that Argentina pulled out of these contracts due to pressure from the United States’ government, which even in the late nineteen eighties was concerned at Tehran’s wish to develop its nuclear industry.

Warrants were issued through Interpol for the arrest of several high-ranking Iranian officials whom Nisman wanted to question in Argentina, but none of them has ever been picked up.

Since 2007, Nisman’s investigation also appeared to be making little progress. Then in 2014, Mr. Nisman claimed to have evidence that the Argentine president and foreign minister had made an agreement with the Iranian authorities under which the two sides would jointly investigate what had happened at the AMIA.

In 2007, the then president Nestor Kirchner had used a speech to the United Nations’ general assembly to accuse the authorities in Iran of blocking the investigation into the bombing.

Now Nisman alleged that Kirchner’s widow and successor as head of state had made a secret deal with Tehran so that Argentina could receive cheap oil from the Iranians.

The day before he was due to present his report to Congress, he was found dead in his bathroom. The door was apparently locked from the inside, and a gun was found next to his body. Although he was supposed to be guarded round the clock, none of his security agents appears to have noticed anything suspicious.

The plot thickens

The judge investigating the death of Nisman, Viviana Klein, has summoned the senior SI (formerly SIDE) intelligence official Antonio Horacio “Jaime” Stiuso to give evidence to her enquiry this week. Stiuso had worked closely with Nisman and is reported to have phoned him several times in the days before his death. President Kirchner has given explicit permission for Stiuso to respond ‘freely’ to the judge’s questions. Stiuso, who has a long and murky past as a spy, extending back at least 42 years. He may speak, but whether he will tell the truth remains very doubtful.

The judge investigating the death of Nisman, Viviana Klein, has summoned the senior SI (formerly SIDE) intelligence official Antonio Horacio “Jaime” Stiuso to give evidence to her enquiry this week. Stiuso had worked closely with Nisman and is reported to have phoned him several times in the days before his death. President Kirchner has given explicit permission for Stiuso to respond ‘freely’ to the judge’s questions. Stiuso, who has a long and murky past as a spy, extending back at least 42 years. He may speak, but whether he will tell the truth remains very doubtful.

Meanwhile, prosecutors and the judicial employees’ union have announced a ‘silent march’ for February 18 to process from the Congress to the building where Nisman had his office. Although the organisers insist that this is intended as ‘a march against nobody… for silence and respect.’, leaders of all the main opposition parties have pledged to attend. The march seems certain to provoke extreme reactions. Writing in Pagina 12, the author Mempo Giardinelli described its organisers as ‘authoritarians, nostalgic for dictatorship, anti-democratic and now in favour of a coup.’

For his part, Verbitsky has concluded that we may never know why Nisman died and, if he was murdered, who was responsible.

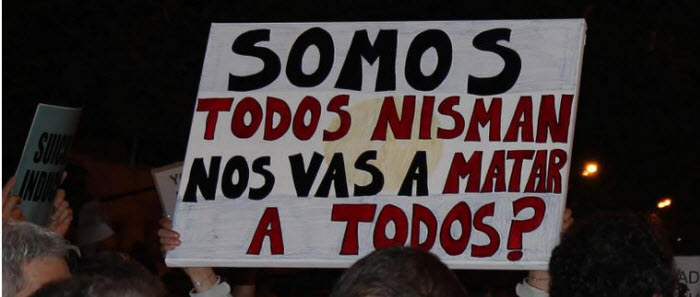

Main image: protest against Nisman’s death. Photo: J.Malievi via Flickr