DEATH OF A PETTY TYRANT

by Nick Caistor for LAB

1 December 2011

‘I heard a voice telling them to apply the electric current to me. Afterwards, I was able to lift a corner of my blindfold, and saw that the person speaking was General Bussi’. Emma del Valle Aguirre was one of the lucky ones: she survived the torture and mistreatment she suffered in one of the more than 30 secret detention centres set up by General Antonio Bussi in Tucumán province during the years of the military dictatorships in Argentina from 1976 to 1983.

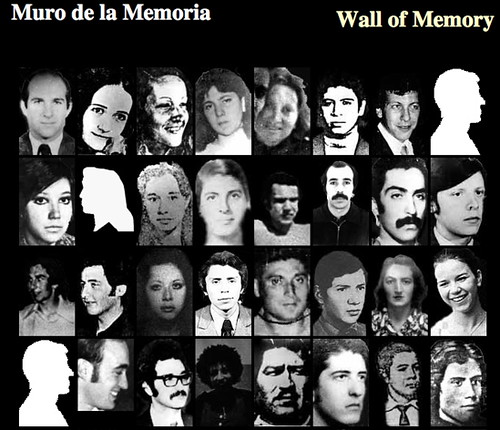

More than a thousand other people snatched off the streets or in their homes or work places in the province were not so fortunate.  Former conscripts who took part in these operations have since come forward to give testimony about the ‘disappearances’ that took place under Bussi’s command. One of them recalled how the general personally came and gave two prisoners the coup de grace in the back of the head before ordering their bodies be burnt and buried in a pit along with two dozen others. Another former gendarme spoke of General Bussi torturing other prisoners with a hosepipe before finishing them off with his army pistol.

Former conscripts who took part in these operations have since come forward to give testimony about the ‘disappearances’ that took place under Bussi’s command. One of them recalled how the general personally came and gave two prisoners the coup de grace in the back of the head before ordering their bodies be burnt and buried in a pit along with two dozen others. Another former gendarme spoke of General Bussi torturing other prisoners with a hosepipe before finishing them off with his army pistol.

General Bussi first took command in Tucumán province at the end of 1975. Although at the time Argentina was still governed by a civilian administration under the hapless Isabel Perón, the country was increasingly divided between left-wing groups who thought this was an opportunity to overthrow the state, and the armed forces, who were determined to resist any change of this sort.

The ERO, or ‘People’s Revolutionary Army’ followed the line of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. They thought they could bring revolution to Argentina by setting up a small guerrilla foco in Tucumán, a poor rural area of northern Argentina, and building up overwhelming support as Che and Fidel Castro had done in 1950s Cuba. But the Argentine military of the 1970s were far better-trained and more resolute than Batista’s men. ‘Operation Independence’ was launched against the ERP, who were quickly destroyed as a fighting force.

Tactics learnt in the USA

The men in charge of the campaign against the ERP were Generals Acdel Vilas and Luciano Menéndez, who later went on to be the ill-fated ‘governor’ of the Malvinas/Falklands after the Argentine occupation of the islands in 1982. It was only at the end of 1975 that Bussi took over from them, complaining that ‘you’ve done the job already’, and that there was hardly anyone left for him to kill. Even so, he put into practice the anti-insurgency tactics he had learnt with the US Army at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, and as a military observer in Vietnam, and the ERP was quickly completely crushed.

In March 1976 the Argentine military pushed Isabel Perón aside and took over power. Political institutions were shut down at all levels,

and Bussi was named ‘interventor’ or military governor of Tucumán province. During his two years as governor, more than 1,000 people are said to have disappeared in the province at the hands of the security forces. Nunca Más, the report on these disappeared people, published in 1985 after the return of civilian rule, said that under Bussi: ‘the province of Tucumán enjoyed the sinister privilege of having created the ‘institution’ of the clandestine detention centre as one of the basic tools of the system of repression used in the military dictatorship in Argentina.’

Bussi himself always maintained that he fought a ‘clean war’ against ‘subversives’. Even in recent years he repeatedly claimed that ‘the delinquents were trying to convert Argentina into a satellite of international communism’; he also said that the concept of the ‘disappeared’ was ‘a subterfuge by the subversives to disguise how many they lost fighting.’

In the 1980s Bussi was saved from prosecution for any of these crimes thanks to the ‘Full Stop’ decree brought in by President Alfonsín, which put an end to the trials against former military commanders. Bussi took advantage of this to launch his own political party, founding Republican Force in 1988. The following year he was elected to the National Assembly in Buenos Aires, where he served until 1995, when he became governor of Tucumán province again, this time as a civilian. His successful political career demonstrated how divided Argentine society continued to be: many on the right still saw him as their saviour even when the truth about the atrocities he had committed became public knowledge.

Suspension

But the general ran into more trouble in 1998, when he was suspended from the governorship for not revealing secret bank accounts he held in Switzerland. ‘I’m not going to either confirm or deny it’ was his only comment at the time. In the end however, it was this rather than the repression he masterminded which led to his being cashiered from the army, after more secret bank accounts were discovered, as well as the ownership of at least 17 properties in Buenos Aires.

In 2003, he was elected mayor of San Miguel de Tucumán, but once again was unable to take up office, as he was arrested for the 1976 capture and disappearance of the provincial senator Guillermo Vargas Aignasse, whose son he had narrowly defeated in the election.

In that same year 2003, the Néstor Kirchner administration renewed trials against prominent members of the military dictatorships. Bussi was tried for the death of Vargas Aignasse, and sentenced to life imprisonment. More than 200 other cases of torture and forced disappearance were prepared against him, but by 2008 he was judged to be in such poor health that these were not pursued.

Even so, further details of his repressive rule came out in recent years, when Bussi himself took a lawsuit out against Tomás Eloy Martínez. The writer and journalist had accused him of being the ‘petty tyrant of Tucumán’, and had written about one of his cruellest crimes: the roundup in 1976 of many beggars from the streets of San Miguel de Tucumán and had them transported to the desert regions of the neighbouring province of Catamarca.

Buss never went to prison for his crimes. He served his sentence in a country club in Tucumán province, but in 2011 suffered a final humiliation when President Cristina Kirchner ordered he be stripped of his rank as general. After his death, the founder of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, Estela de Carlotto said: ‘He took his secrets with him to the grave. He never confessed to anything, never repented, and in fact swore he would do it again…He did not even help us find our grandchildren, so we have to go on drilling at the rock.’