In the fourth article about the CAMeNA history archive in Mexico (you can read the first here, second here and third here), Cornelia Gräbner focuses on the courage of women political prisoners held in prisons such as Villa Devoto, in Buenos Aires province.

‘Let’s see if you can imagine it’, says Alicia Carriquiriborde, ‘It’s like a block, a large space, like a corridor. In its centre are tables and benches made of concrete, and the cells open onto that corridor. I was in cell number 303, or 304, I don’t remember now. So, the cells open onto that space, a locked space, of course, locked by bars. The space didn’t open out onto a yard, or to the outside. In the morning, after they’d brought breakfast, they opened the cells because we had to go and take a shower. The showers were at the end of that corridor. They opened the cells for a few hours, and we could come out into that shared space, or go into other cells to visit each other – for friendship, or camaraderie, or to visit people from the same organisation. After a certain time a siren sounded, and we had to go back into our cells.’

Interview with Alicia Carriquiriborde. Video: forodemcoop2008, 19 September 2008.

Alicia was one of the women who were imprisoned in this cell block in Villa Devoto, one of Argentina’s notorious prisons. During the civilian-military dictatorship (1976-1983) the military junta and their civilian allies deployed the full arsenal of state terrorism to ‘re-organize’ Argentine society into a staunchly patriarchal, capitalist, Catholic, ultra-conservative and reactionary society run by a totalitarian state apparatus. Anyone and anything who did not fit into this vision, or who dared to dissent or resist, was to be crushed and exterminated. People were tortured, assassinated, forcibly disappeared, imprisoned, exiled; the media, cultural bodies and education were censored; the judiciary and all state institutions became tools for the dictatorship.

The prisoners lived four to a cell designed for one person, 25–30 on each cell block. In the face of fear, suffering and constant degrading treatment, they practised between and amongst each other a multitude of small, consistent, everyday resistances. They subverted and opposed attempts to crush them, celebrated the human spirit, sustained and lifted each other up. They found ways to defend and reclaim their minds, their bodies, their hearts, in whatever measure they could. Now, all these years later, Alicia speaks of a co-constructed strength, a shared force.

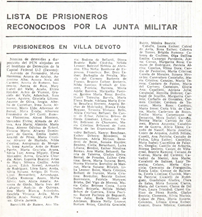

Many of the prisoners in Villa Devoto were arrested as subversives, under the laws put in place as part of the ‘state of exception’. They were detained under ‘executive order’, which meant that there was no trial and no predicted release date. The prisoners in Alicia’s block were mostly young, between 25 and 30 years old, and many of them did not have much political background. Most of those who did were never held in Villa Devoto. Instead, they were forcibly disappeared, kept in clandestine detention centres, and eventually killed. Only very few – among them, Alicia – were eventually transferred into a political prison. Most of the young women Alicia met in Villa Devoto, were snatched because they were someone’s partner, someone’s daughter, someone’s friend, or had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time. But some had been political organizers. And in prison, ‘organisation’ meant to survive: physically, psychologically, spiritually.

None of the prisoners knew when, or if, they would be released. All of them lived in fear of ‘el traslado’, the ‘transfer’, which often meant that the prisoner would be killed , supposedly because of an attempted escape. Their children were raised by family or friends. Many had partners or family members who were also prisoners, or had been forcibly disappeared.

The prisoners rose above the constant anguish thanks to their organisation. They created a shared fund for the products that were brought to them by their family members: sanitary pads, towels, underwear, cigarettes, money to buy coffee, sugar, or any of the products that might lighten their lives even a little bit. They set up discussion and reading groups. They asked their families for coloured towels, which they then unravelled so that they could use the coloured threads for embroidery.

Among their number were a theatre director and a costume designer, and under their guidance they set up artistic and cultural events where they would enact plays or films from memory – films with Charlie Chaplin were amongst the most frequently enacted, because everyone could remember those well enough to re-enact them.

Wherever they could, the women took control of their space and of their bodies. They successfully demanded permission to clean their own cell block. This was done in turns by the inhabitants of the various cells and gave them a chance to leave their cells and visit each other. Although it cost them time in the ‘chancho’, the punishment cells, the women won the right not to be forced to take off their underwear during strip searches. They denounced attempted transfers by collectively banging their aluminium dishes against the bars of their cells, to make so much noise that it could be heard outside, in the middle class and affluent neighbourhood where Villa Devoto was located, and people outside were alerted.

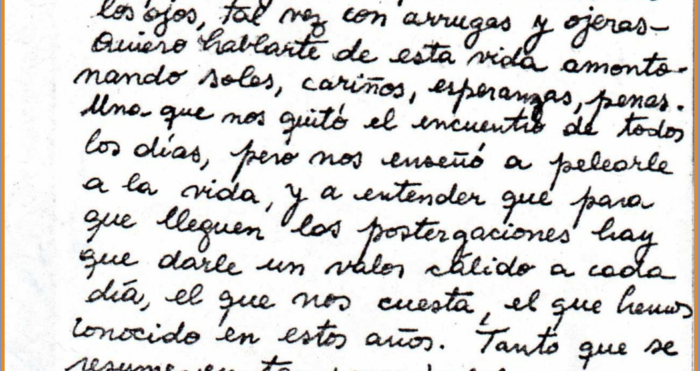

Visits to the prison were crucial, both for their psychological effect and because of the supplies that family members brought. Only immediate relatives were allowed to visit political prisoners. That meant that those who had several family members in prison, had to divide their time between different prisons. The visits took place in cabins, in which the prisoner and the visitor were seated on opposite sides of a screen, and they would communicate through an intercom. It was impossible to physically touch each other, and all conversations were monitored.

During these visits the prisoners did their best to keep up their families’ spirits and support them. They would save a bit of beetroot from their meals to use as rouge, so as not to appear so pale. They would invite their visitors to descargar (unburden) with them or simply to chat about small pleasures: a football game, a birthday celebration.

There was one group who carried messages between the prisoners in different blocks: the transvestites who served the meals. These had usually been arrested for minor infractions of the law related to their sexual identity, and were detained for 30 days. While in jail, they served the meals of the women political prisoners, and with the meals they delivered messages and greetings between blocks and cells.

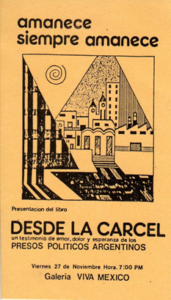

Alicia Carriquiriborde was released in 1978, first into ‘conditional liberty’ (on licence). After one year she was granted permission to leave the country for Mexico, where her husband and children were already exiled. There, with a group of like-minded people she started the group CoSoFam, a non-partisan, non-aligned group that raised awareness about events in Argentina and specifically, about political prisoners. Among their publications was the book Desde la Cárcel, including stories, drawings, prints and poems that celebrate the humanity of the prisoners. When the former chief of security of the clandestine detention centre El Vesubio I was discovered in Mexico in 1985, the remaining members of CoSoFam campaigned for his extradition to Argentina. After the group ceased to exist, Alicia donated their archive to CAMeNA. There, these testaments to ordinary people with indomitable spirits, and the record of the (unsuccessful, as well as abysmally cruel) attempt to dominate and exterminate them, can be consulted under Collection K.

Main image: exterior of Villa Devoto prison. Image: Parabuenosaires.com