Mauricio Macri won the presidency in a political achievement that seemed unthinkable a few weeks ago. Daniel Scioli, the anointed successor to the Kirchners, seemed certain to defeat a candidate that is neither Peronist nor Radical, the main political parties in Argentina. Macri is a wealthy heir who founded a new political party from scratch only ten years ago. Last Sunday it became his main advantage and Daniel Scioli’s biggest problem: Scioli represented continuity with the outgoing president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. Scioli’s vice-president Carlos Zannini was a key figure in the governments of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernandez. But voters didn’t want continuity.

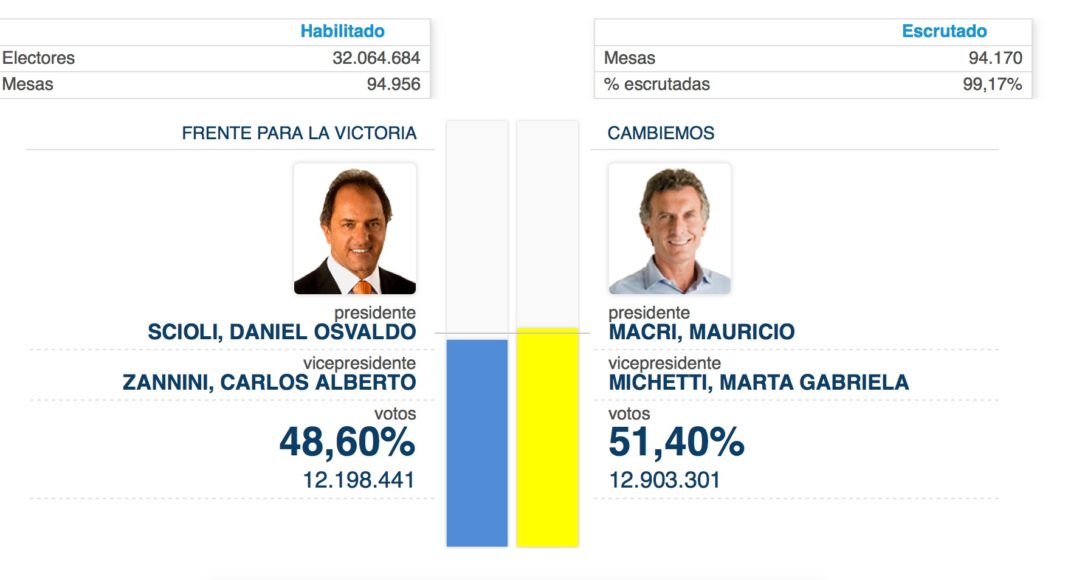

The final result was extremely close, with both candidates garnering 12 million votes, an almost even split of the electorate. But Macri had the edge, with just over 700,000 more votes out of a total of 25 million votes cast.

Realising his mistake, Scioli attempted to distance himself from Kirchnerism after the first round. But to do this he instigated a campaign of fear, predicting catastrophic effects if Macri reached the presidency. Arguably, the majority of the country has voted against Kirchnerism, rather than for Macri.

Just over half the nation feels that the Kirchners are responsible for dividing Argentine society between supporters and opposition, fostering polarisation. Voters also voted against corruption. They are hopeful that Macri’s new government will signify more respect for the rule of law, tackling the politicisation of the judiciary as well as the economic controls isolating Argentina from global markets. Macri’s first headlines have been that he will be ‘implacable against corruption’, but as veteran journalist Santiago O’Donnell points out, he said that when he took over as Buenos Aires mayor, and nobody lost their job.

Macri and his campaign manager Marcos Peña (now to become his Chief of Staff) understood the dissatisfaction with Kirchnerism and made “change” (Cambiemos) the heart of his political project and campaign. But change, in practice, will be harder to organise than the balloons offered during the campaign. Macri will have to work with a Congress that is controlled by the opposition and with the majority of provincial governors who represent the Frente para la Victoria (Cristina Fernandez’s party).

The result of the election opens up a novel political context for Argentina. It is the first time the liberal right reaches power through the ballot box and not through a coup. For its part, Peronism will face a questioning of its political direction after 12 years of the Kirchners in power. Yet overall, it was a vote against: against fear, against divisiveness, against hubris. That much united the disparate voters who turned to Macri – and now it is his turn to show if he can deliver unity in the longer term.