Main image: La Paz, with the Illimani mountain in the background. Source: EEJCC / CC 4.0, Wikimedia.

N.B. Statistics for infection and death-rates shown in images may differ from those in the text of this article

Until now, Bolivia has faced the global pandemic of Covid-19 with fewer deaths and infections than some other countries in the region. Up to 5 May there were 1,802 people infected and 86 deaths. During these last weeks of lock-down and movement restrictions, it’s clear that there have been some achievements in the current Government’s handling of the health crisis, but also some failures.

Success of lock-down measures

Restrictions to limit the spread of the virus started three days after the first confirmed case of coronavirus in the country, on 10 March. On 22 March the Government ordered a complete quarantine, a measure that has since been extended at least four times. According to the latest official announcement total lock-down will finish on 10 May, after which the authorities will relax specific restrictions selectively, according to the situation in each region.

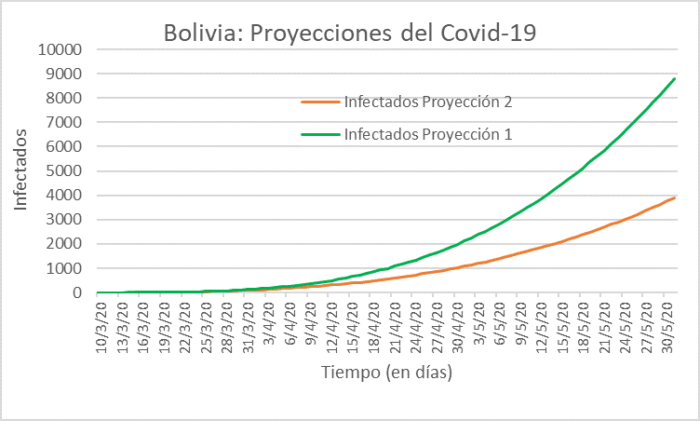

The Health Ministry has said that lock-down reduced the virus spread by 57 per cent to the end of April. A study made by Bolivian experts obtained similar estimates. With some exceptions, Bolivian citizens had respected the lock-down with more discipline than other countries, according to Google data. The Government punished anyone caught flouting the restrictions with fines of Bs. 1,000 to 2,000 (£116 to £233). In some extreme cases, offenders were charged with crimes against public health and sent to prison.

Until 3 May there were 6 deaths per million people in Bolivia, a rate just above that of four South American countries: Argentina 5, Uruguay 5, Paraguay 1, and Venezuela 0.4, according to data for each country compiled by the website worlddometers. The situation in Bolivia seems better than in some other countries, where there have been overcrowded hospitals and human bodies on the streets of some cities. This, supposedly, is thanks to the lock-down and social distance measures imposed by the Government.

Economic safety-nets

On the other hand, the Government has announced at least three special benefits of Bs. 500 each (£58) for people with low or no regular incomes to alleviate the hunger and economic difficulties faced by thousands of families. There are also other benefits for companies to reduce the post-coronavirus economic crisis as much as possible.

However, while these measures help, they are not enough and not everybody that needs the financial aid – whether companies or individual citizens – will be able to access these payments, for different reasons.

Testing

One explanation for the apparently low level of infections could be not just the effectiveness of lock-down, but the paucity of Covid-19 testing. Bolivia is probably the country with fewest tests per million population. A total of 7,651 tests were carried out up to 3 May. At around 655 tests per million people, it is the lowest level in South America.

By the same date, Argentina had carried out 1,456 tests per million people, Brazil 1,597, Chile 10,788, Colombia 2,252, Ecuador 4,458, Paraguay 1,509, Peru 11,376, Uruguay 6,903, and Venezuela 16,802.

Therefore, there is no reliable data about how many Bolivians are infected. Some experts think the official figure represents just 20 per cent of the real number.

In mid-April, the Ambassador of Science and Technology, Mohammed Mostajo Radji, announced the arrival of 450,000 new test kits for coronavirus. On 7 April the former Minister of Health, Aníbal Cruz, said that Bolivia will be able to process 1,342 tests per day with the new equipment. However, until 5 May there were no signs of these medical supplies arriving.

We can conclude, then, that the real number of infections is considerably underreported. The Government, however, stated that if there had been too many infections the hospitals would have collapsed and we would be seeing corpses on the streets, as happened in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Transparency and elections

Another failure was the absence of transparency in the administration of financial resources during this health emergency. Press reports and opposition politicians denounced last week the absence of reports about contracts and purchases made by the central Government during this pandemic. According to an official announcement, this is because no payments were made before the end of April, so there is no need to publish information about the purchases before the supplies are delivered.

It is important to mention that following these complaints the Government launched a website to document state expenditure in this crisis.

As always in Bolivia, political discussions and controversies became obstacles to effective measures to control the pandemic. The interim Government and the opposition now formed by the Movement for Socialism (MAS) are constantly at loggerheads in the middle of these chaotic times, instead of negotiating agreements to support and protect the people.

In areas that had typically backed Evo Morales, the leader of MAS, some people defied the law for political reasons. In Chapare (Cochabamba), Morales’s main support-base, some people drove out police officers who went there to control the lock-down measures and allow banks to reopen in order to pay out benefits for poor people. The worst excesses occurred in El Alto where road-blocks were set up, and buses transporting health workers were attacked with stones.

These actions by MAS supporters were made to protest against the quarantine and to demand prompt elections. The presidential election in October 2019 had been declared null, with MAS accused of committing electoral fraud. An interim government took power, headed by Jeanine Añez, and new elections were due to be held on 3 May, but these were postponed because of the Covid-19 crisis.

The Electoral Court has since proposed that the new elections should be held between 7 Juneand 6 September, depending on the evolution of the pandemic. But MAS politicians are trying to shorten the waiting time even if this represents a risk for the people.

Last, but not least, in this list of failures in the fight against coronavirus, is the rickety Bolivian health system. The current government blames former president Morales for not investing enough money in this important sector. There may be some truth in this, but no other previous government had invested enough in hospitals, doctors, medical equipment and health workers. It may be doubted whether even the current president would pay attention to this area if it were not for the pandemic.