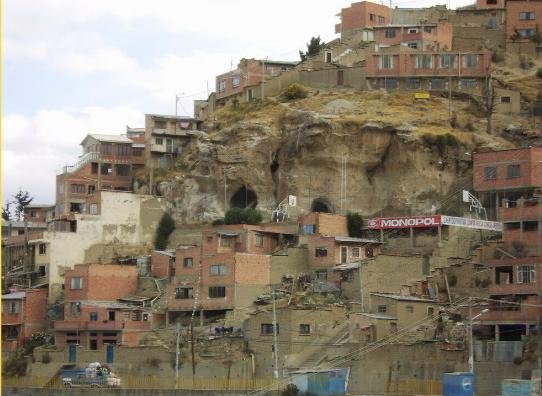

With its 850,000 inhabitants, La Paz, Bolivia, is the world highest “de facto” capital city. It rises from the valley of the river Choqueyapu at 2,800 metres to 4,000 metres in the high Andes Mountains. Apart from its steep slopes (some are above 45% gradient), La Paz’s soil is extremely unstable due to as many as 300 subterranean rivers traversing the city. During the rainy season (December to March), the situation is exacerbated, as the lack of appropriate drainage and sewage system causes flooding, saturation of soil and landslides, particularly on the densely populated hillsides of the city periphery. This situation has been made worse in recent years due to the effects of climate change with increasingly extreme weather conditions.

The government’s Urban Development Plan (1978) established that 40% of the land within the city area was unsuitable for any type of construction. This was confirmed by the Plan for Urban Organisation (GMLP, 2002). According to the report, only 3% of the city is suitable for any type of construction, although 180,000 people live in these areas; 40% of the city cannot be adjusted to make housing safe, (30,000 people live in these areas); and 32% of the city is regarded as unsafe to build on, (approximately 410,000 people live in areas of this kind). In total therefore, more than 45 percent of the population of La Paz is established in areas of risk.

Since the year 2000, there has been a noticeable increase in the frequency of landslides in La Paz, and on 26th February 2011, southern zones were hit by a so-called ‘mega-landslide.’ This was the worst single landslide disaster experienced in the Bolivia’s most populated city in terms of the amount of land, the number of different districts and the amount of people affected. The mega-landslide caused the loss of 223 hectares of land, affecting 1,467 properties and 5,500 people. The economic cost was estimated at approximately US$ 92 million; more than half the annual municipal budget, and the equivalent of nearly all investment in prevention in the previous 10 years.

In 2010, Oxfam in Bolivia started a Landslide Preparedness Project. In co-ordination with multiple stakeholders (local government, INGOs, donors), an early warning system and preparedness measures were put in place. These included awareness-raising among at-risk settlements as well as advocacy towards the European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO) to provide emergency funds before any future disaster. A consortium was created, including Oxfam, Helpage, UNDP and the La Paz municipal government, to create a model of displacement camp for potential victims with 360 temporary shelters, a communal house, a school, and UNICEF WASH services.

The mega-landslide occurred on the very day the camp was inaugurated. Thanks to the existing plan, people made homeless were successfully evacuated, and nobody was killed or seriously injured. In comparison a less extensive landslide in 2002 resulted in 70 deaths. The model camp was replicated by other NGOs and by the authorities to shelter the displaced families, multiplying by three Oxfam’s impact.

The mega-landslide occurred on the very day the camp was inaugurated. Thanks to the existing plan, people made homeless were successfully evacuated, and nobody was killed or seriously injured. In comparison a less extensive landslide in 2002 resulted in 70 deaths. The model camp was replicated by other NGOs and by the authorities to shelter the displaced families, multiplying by three Oxfam’s impact.

In the wake of the 2011 disaster, the Consortium worked with the La Paz municipality to help develop its capacity for emergency response; to relocate displaced communities; and to adopt and implement adequate long-term urban planning and policies, in particular the implementation of the La Paz 2040 Development Plan (http://www.lapaz.bo/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=6147&Itemid=631). A public campaign has also been running to raise awareness of existing risks and to promote a culture of risk reduction, through a television soap-opera, comics and radio programmes.