This article was written in early March, before the effects of Covid-19 virus became clear. Since then the national elections scheduled for 3 May have been postponed, at least until June, but almost certainly until October or later. The postponement was announced by the Supreme Electoral Court on 21 March, although no new date was fixed.

The interim president is a woman

After the 2019 elections, the violent demonstrations and the resignation of the President Evo Morales, Bolivia’s stability is at risk. After Morales’ departure, the country was in chaos and no one was in charge. The political vacuum paved the way for Jeanine Añez, the Senator of Beni, a tropical region of Bolivia, to take power. Añez was at the time the second vice-president of the Bolivian Senate. The resignations suddenly made her first in line to assume the interim presidency under the Constitution, although the legality of this is disputed.

Jeanine Añez thus became only the second female president in Bolivian history. The first was Lidia Gueiler Tejada, also an interim president, in 1979–1980.

At the outset, Añez promised she would only hold power until elections were organized. Shortly afterwards however, on 24 January, she announced her candidature at the elections on 3 May 2020.

Currently Bolivia has six candidates for the office of president, five men and one woman. All six have different backgrounds and different ideas to shape their country.

Equal representation in parliament

One interesting question is the likely effects on female representation and women´s rights after the elections. Why is this so interesting? Because Bolivia by 2019 had become an exception to most of Latin America and the world, with 53% women in the Cámara de Diputados and 47% in the Cámara de Senadores. In the last decade under the government of Evo Morales and with a new constitution, the path for women to exercise power in Bolivia had opened up.

In 2019, according to a publication by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), the proportion of women in parliaments worldwide averaged 24.5%. A balanced representation of women and men is still an exception: in only four states in the world the proportion of women in parliament above or equal to 50%. Yet at the same time Bolivia is known as a patriarchal state with high rates of femicide and violence against women and girls, even in politics.

So how do those two contradictory images of one country fit together? How did women come to power? And how will these advances fare under a new government?

Latin America’s first state to enshrine gender equality

Bolivia is the only country to require gender equality in representation at national level. The effect of the gender quota laws is visible in the changed composition of the Bolivian parliament: Since 2014, 49% of the seats in parliament have been occupied by women and since March 2015, more than 51% of the seats in local councils. This is a remarkable result in a country where the right to vote was only won by all women in 1952 and women were not considered fully equal until the 2009 constitution.

The first quota laws aimed at reducing gender inequalities in politics and guaranteeing the effective fulfillment of women´s political rights, were approved in Bolivia in 1997. It became one of the first Latin American countries to adopt a law on parity and alternation for elections. After several judicial and constitutional changes to the quota laws, Bolivia reached the goal of 52 percent of women in parliament by 2014.

Thus, in Bolivia, women found their way into politics through quota laws. This success can be traced back to the efforts of the women’s movements since the 1990s. They used the opportunity in the reform process to voice their concerns. The political elites aspired to gain more legitimacy for their institutions, and the promotion of women fitted perfectly into this quest. The Bartolinas were the actors who wanted above all to strengthen the rights of peasant women and rural communities. But the women of the urban middle class also demanded the implementation of their human rights. The main political parties supported the demands for stronger representation of women above all in order to strengthen national political goals, development processes and their ideological position.

Politics in Bolivia is based on the twin pillars of the institutions of government and state on the one hand, and the streets and civil organizations on the other.

The main actors in the inclusion process have changed over time. In the beginning there were the traditional parties and middle-class women, later campesinas and indigenous leaders joined in. Over time, women’s groups remained the driving force. However, there was also support from the state. Women were therefore able to voice their concerns through collective action and with the involvement of public institutions. Women’s organizations had waited for the moment of change and transformation in politics to bring their concerns to bear. Politicians reacted positively to these demands because they too wanted to distance themselves from the traditional system which had excluded women.

The role of civil society

Since 1997 several laws have been passed in order to achieve parity. First in 1997, a quota of 25% was introduced. The law was mainly the result of the work of various activists and organizations, especially the Foro Político de las Mujeres, formed by Bolivian politicians and activists from various social organizations and connected with international development organizations. The Foro had a clear vision about the need for quota laws and was certain that the parties would only implement quota if it was made obligatory. Afterwards more electoral laws were passed and more or less effectively fulfilled. The politicians played tricks, attempting to safeguard the interests of male candidates. For instance, the names of some male candidates were changed to female names, so a ‘Victor’ became a ‘Victoria’. There was still a long way to go towards parity and alternation.

As a result, further legislation was passed, considered as a harbinger of the new constitution of 2009. The Ley de Partidos Políticos was adopted in 1999, and prohibits any discrimination based on gender, generation, ethnicity and culture. It also stipulates that every party must adopt internal rules that guarantee the participation of women.

The new constitution

The 2009 constitution guaranteed the protection of the newly won promotion of women and made further important legal progress in political participation of women and a life free from violence. It is an inclusive constitution, which reflects the changed political situation and is part of a new variant of Latin American constitutionalism. These new constitutions extend the protection of social rights and of marginalized and excluded population groups. For example, the constitution speaks of ‘las bolivianas y los bolivianos’.

Another milestone in Bolivian politics was reached in 2012, when both legislative chambers elected a female president. This was mainly due to the hard work and activism of civil society organizations, not to any ‘generous’ concession by the political elites.

Since 2014, then, women have been present in Bolivian politics on an equal footing with men. The most obvious change produced by this female empowerment in politics, has been the laws about violence against women with a special focus on women who are active in politics. Bolivia is the first country worldwide which adopted a special law about the violence against women who participate in politics (Law 243 of May 2012). Several other laws followed, but most the important change has been the growing visibility of women in politics. There are still many obstacles women have to confront in everyday life and as politicians, but changes are happening. It is devoutly to be hoped therefore that democratic and free elections will take place soon and that that Bolivia will continue its progress to become a model state in terms of political representation of women.

A woman, but a conservative

In the three months of her reign, Jeanine Añez, has emerged as an authoritarian and radical figure. On one hand she cut diplomatic relations with Mexico, Spain and Cuba, on the other she concerted a rapprochement with the Brazilian ultra-right president Bolsonaro. An apparently glamorous woman, Añez entered the Palacio de Gobierno with a bible in her hand, saying: ‘the bible has returned to the Palacio de Gobierno’.

After graduating from law school, her career started as a news anchor at a local television station in Beni. As one of the few prominent women in public, she was put forward as a member of the constituent assembly. There her political career started and the party Plan Progreso para Bolivia-Convergencia Nacional (PPB-CN) adopted her as candidate for senator of Beni.

Añez’ elevation to the presidency presents a difficult challenge for Bolivian women. At last there is a female candidate for president, but Jeanine Añez promotes conservative politics. As Sylvia Colombo said in a comment in February 2020 in The New York Times, it seems that Añez represents a point of view that white women with European ancestors in Bolivian cities want to hear. Añez herself has some indigenous features, but has sent the military into the streets to oppress people with her own ethnic characteristics.

In her political beliefs and practice, Añez follows a conservative agenda. Conservative politics has two basic principles, the strong rule of law and the protection of the traditional ways of living. This involves, for example, the classic nuclear family and the traditional role of women in society, where women are definitely not expected to engage in politics or become leaders. This traditional image of women is much more about the oppression of women, not social progress.

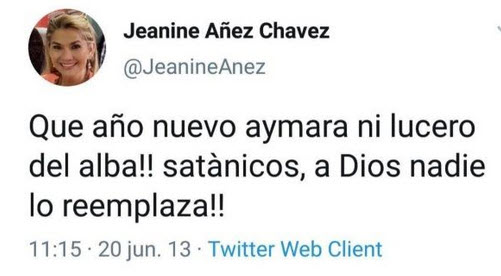

Añez has also adopted brutal measures against indigenous groups and political opponents, measures that are scarcely conducive to the preservation of a stable democracy. Her polemical and racist comments about the indigenous population have aroused national controversy in the past. She tweeted in 2013 at Aymara New Year, that ‘no one will replace god and those you who believe different are Satanists’, betraying open hostility towards freedom of belief and the traditions of the indigenous people, who make up 41% of the Bolivian people. It appears that democracy is more threatened now than before the October 2019 elections.

On the other hand, Bolivian civil society has been awakened by these events and is fighting for its rights and freedoms. The many active women’s organizations will ensure that women’s rights are strongly represented.

International bodies such as the UN promote the empowerment of women. Therefore, a violation of women’s rights and other human rights would mean a loss of international legitimacy for a conservative, authoritarian government under Añez.

Nevertheless, it is still too early to assess what it would mean for the political representation of women if a conservative government came to power in the next elections. One thing is certain: women in Bolivia have fought hard for their rights and will not give them up easily. Moreover, the quota for women’s representation is anchored in the constitution so that it can be enforced.

The example of Jeanine Añez clearly shows that women in politics do not necessarily pursue women-friendly policies.

There is much criticism of Añez from all sides. However, her own gender has not been explicitly criticized from any side. This shows that there has been a real change in Bolivian society and that the acceptance of women in leading positions is increasing. It is all the more important that progressive women’s rights policies are defended, and that civil society continues to stand up strongly for women’s rights.

Christina Klingler is completing a Masters degree on the participation of women in Bolivian politics.

Bibliography

Choque Aldana, M., 2013. Paridad y alternancia en Bolivia. Avances y desafios de la participación de las mujeres en la política. La apuesta por la paridad: democratizando el sistema político en América Latina. Los casos de Ecuador, Bolivia y Costa Rica, Mai, pp. 121-175.

Choque Aldana, M., 2014. Avances en la participación política de las mujeres. Caminos, agendas y nuevas estrategias de las mujeres hacia la paridad en Bolivia. Revista Derecho Electoral, Issue No. 17, pp. 333-356.

Coordinadora de la Mujer, 2011. Celebrando 100 años del Día Internacional de la Mujer. Qué logros hemos obtenido y qué desafíos nos quedan por afrontar?, La Paz: Coordinadora de la Mujer.

Costa Benavides, J., 2003. Women´s Political Participation in Boliva: Progress and Obsticales. Lima: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance IDEA .

Grote , R., 2019. Verfassungsrecht – Von der Rezeption zur Transformation. In: G. Maihold, H. Sangmeister & N. Werz , Hrsg. Lateinamerika – Handbuch für wissenschaft und Studium. Baden- Baden: Nomos Verlag, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, pp. 133 – 144

Klingler, Christina. 2020. Repräsentation von Frauen im bolivianischen Parlament. Analyse der substantiellen Repräsentation von Frauen im bolivianischen Parlament anhand der Repräsentationstheorien von H.Pitkin. European University Viadrina, Frankfurt (Oder)

Krook , M. L., 2008. Quota Laws for Women in Politics: Implications for Feminist Practice. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, States & Society, 08 August, Volume 15(3), pp. 345-368.

Krook, M. L., 2009. Quotas for women in politics – Gender and Candidate Selection Reform Worldwide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krook, M. L., 2017. Violence against women in politics. Journal of Democracy, 1 Januar, Issue Vol. 28, pp. 74-88.

Krook, M. L., 2018. Violence against Women in Politics: A Rising Global Trend. Politics & Gender, Band 14, pp. 673-701.

Novillo Gonzáles, M. A., 2015. Más alla de los números: Las mujeres transforman el Poder Legilativo, s.l.: UNDP.

Rousseau, S., 2019. Bolivia: Parity, Empowerment, and Institutional Change. In: The Palagrave Handbook of Women´s Political Rights. London: Springer Nature Limited, pp. 393- 403.

Sànchez, M. d. C., 2015. Détras de los números: Las trayectorias de la Paridad y la Igualdad en un contexto patriachal, La Paz: Coordinadora de la Mujer. Sànchez, M. d. C., 2015. Participación Política de las mujeres en el Estado, La Paz: Instituto Internacional para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral IDEA.