- President Michel Temer issued a presidential decree in 2017 to open up the vast 4.6 million hectare (17,800 square mile) RENCA preserve in the northern Amazon to mining. Meeting with a firestorm of criticism he abandoned the effort. Sources now say the Bolsonaro administration is poised to quietly revive plans to open RENCA in 2020.

- Likewise, with Bolsonaro in charge, transnational mining companies are pushing for a change in Brazilian law allowing the firms to mine inside protected lands and indigenous reserves across the nation. The change could be introduced in 2020 via the mining law, a bill long stalled in Congress.

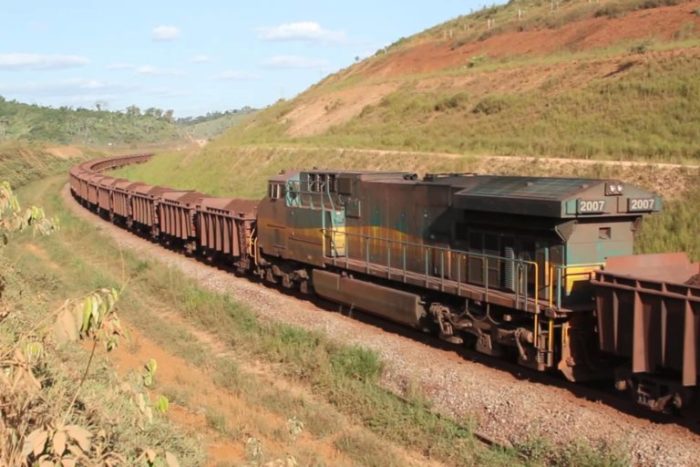

- Should mines in RENCA and elsewhere go ahead, transport will be needed. The planned Ferrovia Pará railway (Fepasa) would move commodities from Pará state’s interior for river transport to the coast. Other plans call for 20+ new river ports, 2 thermoelectric power stations, and a transmission line crossing Pará.

- However, all these major projects face a legal hurdle. The Brazilian Constitution states that no major measure can be authorized allowing mining in indigenous areas, or large new infrastructure projects approved before prerequisites are satisfied, including consent of affected indigenous and traditional communities.

- This article was first published on Mongabay on 31 December 2019. You can read the original here.

For decades, since the end of the military dictatorship in 1985, Brazil’s government has struggled to strike a balance in the Amazon between moneyed ruralist interests allied with transnational agribusiness and mining companies, and their opposition — indigenous peoples, conservationists, and traditional riverine, minority and landless communities.

But Jair Bolsonaro’s government is proving to be a game changer — an administration uninterested in balance or compromise, and seeming not to care about world opinion or reputation, going its own way. It has already approved, or is moving toward approving, a slate of initiatives aimed at deregulating the environment and cancelling out many social gains, while generating an unprecedented expansion of land grabbing, agribusiness and industrial mining.

This is the second of two articles in which Mongabay surveys examples of key measures carried out so far, along with what may lay ahead. The first article concentrated on land grabbing and agribusiness, the main focus in this story is the administration’s alliance with mining interests.

Opening RENCA

When President Michel Temer issued a presidential decree in August 2017 to open up the vast 4.6 million hectare (17,800 square mile) RENCA preserve in the northern Amazon to mining, he met with a firestorm of criticism. RENCA (the National Copper and Associated Reserve) is in Amapá, Brazil’s most northern state, where it borders on Pará. The military set it up in 1984, not to protect the rainforest but to stop transnational mining companies from plundering the country’s resources.

But RENCA’s establishment served conservation needs anyway. Almost all of it (95 percent) is protected today, with seven conservation units and two indigenous reserves. Only 0.3 percent has been deforested, making it one of the Amazon’s most intact rainforests. So it wasn’t surprising that environmentalists were outraged by Temer’s sudden move.

The roar of national and global disapproval caused a federal judge to annul Temer’s decree, ruling that Brazil’s 1988 constitution did not permit the preserve to be abolished by the president, but only through legislative action.

Now, with the ruralists more powerful than ever in Congress and Bolsonaro running things, observers say it is only a matter of time before the government teams up with mining interests to have another go. Indications are, according to Mongabay sources, that they are preparing to act early in 2020.

RENCA is a tantalizing prize. The mineral wealth lying beneath its pristine forests is mind-boggling, with estimated reserves of gold, iron, phosphate, titanium, manganese, niobium and tantalum. “Studies carried out in the 1970s said that [RENCA’s] minerals were worth US$1 trillion,” Senator Lucas Barreto, a chief advocate of opening up the preserve, told the El Pais newspaper. “Imagine how much that is in today’s values.”

Although the generals in power in the early 1980s adopted nationalist policies, particularly in industry, they were also keen to attract foreign mining companies. The creation of RENCA was in some ways an exception. According to the BBC, the British mining company, BP, wanted to mine RENCA, but Rear Admiral Roberto Gama e Silva, a staunch nationalist, told the powerful National Security Council that ceding the mining rights to BP might further the interests of the American, Daniel Ludwig, then one of the richest men in the world, who was at that time opening the Jari agro-industrial project nearby. As a result, mining’s entrée into RENCA was vetoed.

Mining companies have been lobbying since then to end this prohibition, with Canadian firms, in particular, eager to get access to RENCA. Sen. Barreto recently revealed that Bolsonaro has told him that a new version of Temer’s RENCA decree is being prepared. Other presidential sources confirm that action will be taken soon.

There will, again, undoubtedly be protests. “Everyone I have spoken to is horrified at the prospect of abolishing RENCA,” said Randolfe Rodrigues, leader of the Senate opposition, while in Madrid for the COP25 climate summit in December. It seems likely, too, that once again the legality of the decree will be challenged in court, where the outcome is uncertain.

People who know the region well are worried about the impact, not only from the mines, but from the collateral damage that opening up RENCA will do to indigenous communities, traditional populations and the forest. “To gain access to most of the minerals, they’ll have to create a new logistics, with roads, railways, electric energy,” said Décio Yokota, assistant executive of the not-for-profit Institute for Research and Indigenous Training (IEPÉ).

The Bolsonaro government has already made behind the scenes efforts to fast track the long delayed Manaus-Boa Vista powerline through the Waimiri-Atroari Indigenous Territory that would supply electricity from the Tucurui hydroelectric dam to new mines and energy-hungry ore processing plants in RENCA. A proposal floated seemingly out of leftfield at the start of the administration to extend the BR-163 north to the Surinam border could be part of the plan too, though not directly linked to the opening up of RENCA, which is located much farther to the east.

Yokata says that large-scale infrastructure projects like those being considered for RENCA leave only desolation in their wake. “Big hydroelectric dams and mining companies destroy, exploit, extract and leave — and when they leave, they leave nothing behind but their destruction. They don’t generate local wealth,” he said. Instead, he said, the government should invest in sustainable projects that don’t destroy the forest.

Thousands of mining claims already mapped

Meanwhile, with Bolsonaro in charge, mining companies are pushing for a change in Brazilian law that would allow them not only to mine in one preserve, however large and rich, but also on protected and indigenous land throughout the nation. Such a change could be introduced via the mining law long stalled in Congress.

However, a serious legal hurdle stands in the way. The Brazilian Constitution states that no measure can be authorized to allow mining in indigenous areas before a series of prerequisites are satisfied, including the consent of the affected communities.

According to the jurist and former president of the indigenous agency, FUNAI, Carlos Marés, this means that all indigenous people in Brazil must be consulted, in accordance with the guidelines established in the International Labor Organization’s Convention 169, of which Brazil is a signatory. In practice, such approval would seem remote or even impossible.

The government has not yet indicated how it intends to resolve this conundrum. Even so, the National Agency of Mining (ANM), the body responsible for Brazilian mining, has accepted initial proposals from companies for mining in 48 indigenous territories, concessions whose borders have been well mapped.

In late November, the Public Federal Ministry (MPF), a group of federal and state independent litigators, called on the ANM to throw out these proposals until the legal requirements under the Constitution have been met. The ANM argued in return that it can authorize initial studies, provided that the mining itself doesn’t begin until all legal demands are satisfied.

The MPF disagrees, saying that these advance claims indirectly help the mining companies. “Even though these legal procedures don’t by themselves cause socio-environmental damage, they help produce a raft of ‘documents’ that create the appearance of legality for artisanal mining,” stated the MPF. “These documents are used on the ground as a means of keeping the [artisanal] mine[s] open, recruiting laborers, contracting services and even deceiving the Indians.”

According to the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), an NGO, mining companies have registered 3,347 requests for mining rights in seven Amazonian states — Acre, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima and Tocantins. They involve 131 reserves. The lion’s share of the claims are in Pará state, with 2,266 requests.

Infrastructure to prepare the way

Should those mines go forward, they, like agribusiness, will require transport, particularly railways. In that regard, on 12 November, the Pará state government signed a memorandum of understanding to carry out a viability study for the Ferrovia Pará railway, known as Fepasa.

Fepasa would run in a roughly north-south direction, from Parauapebas in southeast Pará, through the town of Marabá on the Tocantins River, to the municipality of Barcarena just west of Belém near the Brazilian coast. The government’s aim: use Fepasa to transport ore and soy from the state’s interior for export via transatlantic vessels through the Amazon River estuary. Construction is slated to begin in 2021, but as yet, none of the impacted indigenous communities have been consulted as required by ILO Convention 169.

The railway is just one component of an ambitious infrastructure master plan to expand the region’s logistic capacity; those plans include the building of at least 20 new river ports, two thermoelectric power stations, and a transmission line running across Pará from north to south. It seems certain that the state’s rainforest could not long survive such an onslaught.

João Gomes, assistant director for the Amazonia Program for the Federation of Organs for Social and Educational Assistance (FASE), agrees that mining and agribusiness concentrate income with wealthy elites while having very serious socio-environmental impacts.

Here too governmental development plans face obstacles, especially environmental regulations. To get round those blocks, the administration is pushing a new bill (PL 3,729) through Congress. It would simplify the environmental evaluation and approval process, collapsing the present three-phase licensing process into just one. Such fast track bills have been produced before, but never to such a cooperative ruralist Congress.

Attacking science and indigenous peoples

The government is attacking the Amazon on other fronts too. Key scientific research bodies, such as the National Institute of Amazonia Research (INPA), and the Emilio Goeldi Museum in Pará, whose studies at times urged authorities to adopt tougher forest protection measures, have had their budgets severely reduced under Bolsonaro.

“Without being able to contract new staff to replace the large number of people who are retiring, our [scientific] institutions are losing brains, productive capacity, communication capacity and training expertise,” said Ana Luísa Albernaz, the Goeldi Museum director.

Archaeologists, too, are facing dramatic funding cuts which will jeopardize their work documenting the Amazon’s rich indigenous prehistory and stopping them from salvaging relics — also, importantly, those cuts prevent digs that could give cause for slowing infrastructure and mining projects.

The Bolsonaro administration has already weakened IBAMA and ICMBio, Brazil’s two main environmental protection agencies, and it has also taken steps to render FUNAI, the country’s indigenous affairs agency, virtually inoperative. Even though weakened in recent years, FUNAI had continued to provide invaluable support to indigenous communities and slowly carried on demarcating indigenous reserves.

All that is ending now. A serious blow for the agency was Bolsonaro’s decision in July to appoint Marcelo Augusto Xavier da Silva, a former police officer with strong connections to agribusiness, as FUNAI president.

Many indigenous leaders were horrified at the time, fearing that his appointment would sound the death knell for the agency. Today it seems their fears were justified.

In November, the Brazilian Association of Anthropologists (ABA) issued a press release in which it charged that FUNAI is now selecting personnel “without the minimum qualifications and legitimacy” to identify and demarcate indigenous land.

One example cited by ABA is the dismantling of two groups set up to identify and demarcate land for the Tuxi and the Pankará indigenous peoples, both inhabiting Pernambuco state in Brazil’s northeast. Bolsonaro’s FUNAI demanded, ABA said, that highly qualified people already chosen to staff those groups be replaced by “trustworthy anthropologists,” code it appears for people who the government trusts to do its bidding, according to critics.

In November, da Silva told FUNAI staff they were banned from visiting land that was in the process of being demarcated, thus barring them from carrying out the verification process that is their charter under the Constitution.

The Estado de S. Paulo newspaper strongly criticized this instruction, saying that “The decision, besides being at odds with FUNAI’s basic mission, which is to act in defense of indigenous rights, also infringes indigenous rights as set out in federal legislation.”

In December, FUNAI started replacing the heads of its regional posts. Eight new coordinators have been appointed so far. A retired Army colonel was chosen to head the office in Dourados in Mato Grosso do Sul, a state where there has been indigenous unrest and a high indigenous suicide rate for many years, likely due to the government’s failure to recognize the lands rights of the Guarani-Kaiowá. A former military officer has also been appointed to head the FUNAI office in Humaitá in Amazonas state. New FUNAI heads are expected to be appointed to all 39 regional offices by the end of January, 2020.

However, the new FUNAI president hasn’t been getting it all his own way. Indigenous organizations have been campaigning continuously and effectively in Brasilia against a proposed constitutional amendment (PEC 215/00) which would transfer authority for demarcating indigenous land from the executive branch, with FUNAI carrying out the studies and the Justice Ministry approving them, to the ruralist-dominated Congress.

PEC 215/00 also includes the so-called “marco temporal,” which would establish an arbitrary cut-off date of 1988 as the year when indigenous groups must have been living on land for that property to be recognized today as theirs. In addition, it requires that non-indigenous Brazilians claiming and living on indigenous lands be paid compensation for any losses, not just for assets but also for the land itself, if forced to leave it.

Congress, through strongly ruralist, is still divided on the marco temporal issue, which requires a two-thirds majority to pass. Voting was postponed twice this year due to vociferous protests held in Brasília by indigenous people and quilombolas, communities of runaway slave descendants.

But far from the federal capital, Indians are paying a heavy price for the impunity with which land grabbers and landowners have operated this year. Seven indigenous leaders were assassinated in 2019, making it the deadliest year for indigenous leaders in two decades. Many analysts believe that things will only get worse in the years ahead if, and when, the mining companies move in.