Brazil’s indigenous peoples face the most serious threats since the military dictatorship: a government determined to eliminate their rights, abolish their culture and ‘integrate’ them into an ultra-neoliberal economy; and a pandemic to which they are particularly vulnerable and which threatens their very existence.

In the first of three articles, LAB correspondent Nayana Fernandez and University of São Paulo (USP) researcher Cauê Tanan explain that, in the last 520 years of the history of these communities, these threats are nothing new.

See the other articles in the series: Pandemonium 2: forest fires and pandemic and Pandemonium 3: resistance and recognition.

Pandemonium – again

The Brazilian government’s disastrous approach towards the major global health crisis of our times, has ample precedent in the country’s history. Equally, indigenous communities engaged in resistance today have, ever since the European invasion in 1500, mounted a determined resistance to their enemies, both the visible, white, male enemies, and the invisible, especially imported disease.

‘I’m wondering if the whites will resist. We’re indigenous people, we’ve been resisting for over 500 years.’

Ailton Krenak, October 2019

Brazil, the size of a continent, emerged as a nation from successive waves of oppression against indigenous and African peoples, and has for centuries provided the setting for immense social problems. Today’s fake discourse on ‘racial democracy’ constitutes one of the most cruel attacks: historical erasure. Intended to bring harmony and tolerance to our national identity, what these racial theories brought instead are perverse ways to uphold the deep-rooted structural racism in our society.

The last country in the Occident to abolish slavery, Brazil has today the third world’s largest prison population, where about 63.7 per cent of prisoners are dark skinned people. This persistent trauma, and the various impressive efforts to stop this humiliating ‘whitening’ nightmare, explain many of the violations people still have to confront.

But, if before the last presidential elections these violations were taking place openly, with an ultra-conservative quasi-military government in charge, life in Brazil has now become routinely exceptional. Indeed, it could be said that a true state of exception became the norm after the parliamentary coup d’etat in 2016, when reactionary groups of the dominant white-male elite, nostalgic for the 1970s dictatorship, laid siege to president Dilma Roussef in order to prepare her impeachment.

Historical overview

Many of us know that violence in Brazil has always been the rule, not the exception. But there were particular periods in history when, as today, things became exponentially worse. Indigenous peoples know well what that means. Throughout history, there have been moments when indigenous peoples had to face assaults on multiple fronts: epidemics, slavery, debt slavery, devastation of territories by deforestation and mining, wars, rape, the demonization and persecution of their shamans by Christians, the systematic assassination of their leaders, elders, sometimes entire villages and last, but not least, confinement in the so-called ‘reformatory’ sites which most of us know as ‘concentration camps’. The last two of these camps in operation were the Krenak Reformatory (1967 – 1972) and the Guarani Farm (1973 – 1979), operating during the dictatorship years.

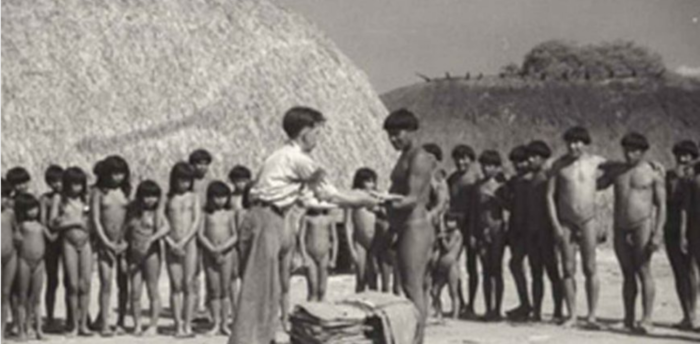

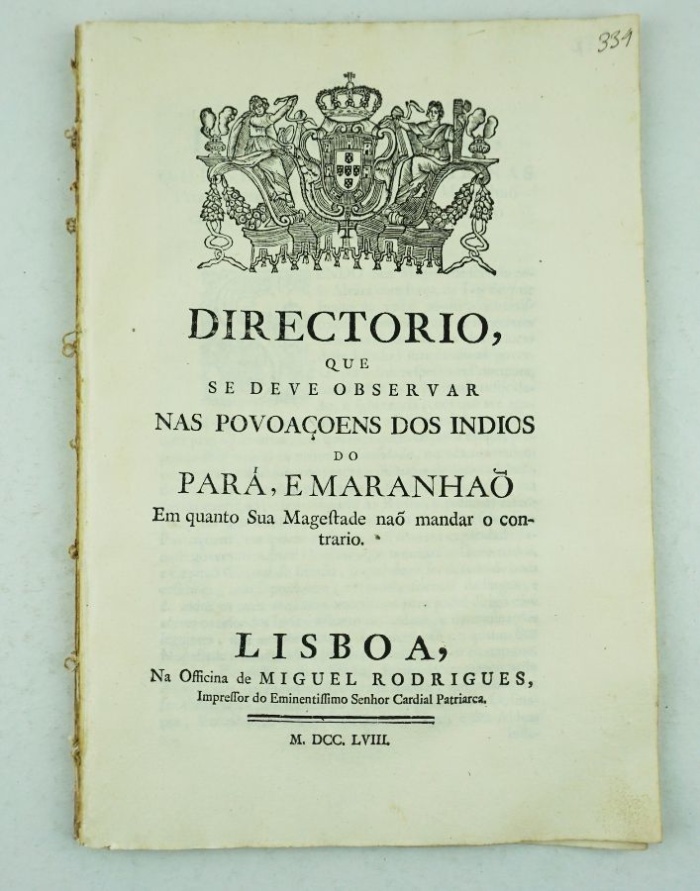

All these devastations were devised or amplified by despotic governments. One of the cruelest periods in the history of indigenous people in Brazil occurred in the 18th century, when the Directorate was established. This indigenist policy was drafted principally by two men: Mendonça Furtado, a military officer, young brother of the prime minister of Portugal at the time, and Miguel de Bulhões, a Dominican bishop, one of the catholic orders that took over from the Jesuits the domination of some indigenous villages. This duo represent the two significant groups which have paved the historical pathway of militarism and Christian ideology since the colonial period.

The Directorate deliberately established a system to ‘reform indigenous habits’, which meant to undermine everyday cultural practices and to alter the social structure of communities. This was frequently followed by attempts at outright extermination. In addition, religious schools were created to separate boys and girls and these served as the means for banning native languages. However one of the most radical guidelines aimed to encourage white men to marry indigenous women. That practice, common even before the Directorate initiative, was then intensified: kidnapping and rape.

The larger the influx of outsiders into the villages, the wider the spread of disease. With insufficient time to develop their own medicines, records show that the usual method of prevention practised by indigenous peoples was to isolate themselves from the white colonisers, proving they were quite aware of the origins of the contagions. In addition, one of the first words that many communities learned or created after initial contact was a name for flu. By contrast, there are no rigorous records of indigenous diseases being transmitted to outsiders apart from certain types of mycosis.

The ‘natural’ theory of disease transmission

Guns, Germs and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies (1997) is a famous book which tries to explain how and why peoples in the Americas were so affected by diseases compared to other peoples around the world. Author Jared Diamond suggests that we should look at infections by viruses and bacteria from the perspective of the viruses and bacteria themselves. He argues that disease transmission is based on natural selection, which guides the movement of pathogens from person to person, spreading them across long distances. But, was that really how it happened?

During the 19th century, for instance, it was commonplace for colonisers to take diseases to indigenous villages across the continent deliberately, in order to steal their territories. This occurred in the case of influenza, measles and smallpox epidemics, for example. The European invasion of territories in Africa and the Americas happened intentionally, motivated by wealth accumulation and religious interests. The slave trade, promoting a large-scale African diaspora, dislocated millions of people over centuries on overcrowded ships with terrible hygiene conditions, and was also a deliberate policy, driven by economic groups of white predominance, who were able to enrich themselves on the proceeds.

This, of course, is not to deny that viruses like the yellow fever mentioned by Diamond, seek hosts in order to survive and reproduce themselves, leading to human death. However, it is unrealistic to suppose that a biological process, which tends to occur locally or regionally, would have spread to very distant places or to the whole world without intensive human intervention.

Sadly, theories such as Diamond’s can lend considerable support to misleading interpretations of very important historical processes and, which is worse, allow racist public policies to be validated and carried out.

In their second article, the authors chart the details of the present situation, as it affects not only the remote communities of the Amazon, but indigenous groups in the Pantanal, the Cerrado, and those living on the margins of cities such as São Paulo. In the final article, they describe how as the situation worsens, indigenous peoples are taking matters into their own hands and winning international recognition for their resistance.