Over the last few weeks there has been an outpouring of solidarity with Dom Pedro Casaldáliga, the retired bishop of the diocese of São Félix do Araguaia, a huge area of 150,000 square kilometres in the north of the Amazonian state of Mato Grosso. In early December, 84 year-old Dom Pedro, who suffers from Parkinson’s and walks with difficulty, had to flee from his home in the small town of São Félix after receiving death threats.

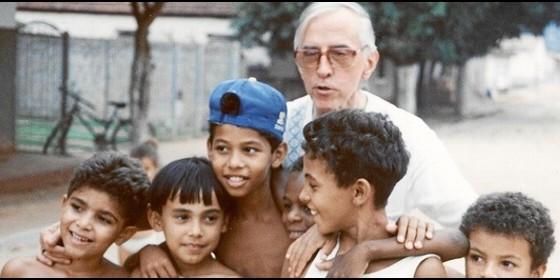

I first met Dom Pedro in his home in São Félix in the mid-1970s, when I was writing a book on land conflict in the region. He is a small thin man, and even then he looked frail. What I remember most is the warmth of his welcome, as he invited me into his sitting room in his simple house – not at all the kind of home one expects for a bishop – and started to explain what was going on in the region.

At that time hundreds of peasant families in the region were losing their land to big companies from the south who were setting up large cattle ranches with tax incentives administered by a notoriously corrupt government agency, SUDAM. Despite the isolation of region and the close alliance betwen the justice system and the landowners, some families were valiantly defending their right to stay on their land. There was considerable bloodshed.

There was never any doubt as to which side Dom Pedro was on. Clearly distressed by the scale of the abuses that were being committed against the peasant families and indians, he thrust into my hands a roughly produced booklet – which I have on my desk beside me to today – in which he and other Catholic priests, part of the then influential liberation theology movement, describe in some detail the land conflicts in the region, involving both peasant families and indians, as well as listing the huge sums of government resources that were being channeled to the ranches.

The book was published just after Dom Pedro was appointed bishop in 1971. This was the most repressive period of the military dictatorship and it was dangerous for anyone, including a bishop, to produce such a document, even if semi-clandestinely. Dom Pedro indirectly acknowledges this in his conclusion where he states: “This injustice has a name: Latifúndio [landed estate] … We hope that no proper-minded Christian will describe this document as subversive. … These pages are the cry of a Church in Amazonia – the Diocese of São Félix in the northeast of Mato Grosso – in conflict with the Latifúndio and threatened by social marginalisation.”

At the same time Dom Pedro was expressing his political views even more explicitly in the poems he was writing. Here, in an extract from one of them, he defiantly defends his right to be ‘subversive’ in the sense he gives the word –something that was potentially very dangerous in those days:

“I encourage subversion against Power and Money.

I want to subvert the Law

that turns the people into a flock of sheep

and the government into a slaughterer.

(My Shepherd became a Lamb,

My King became a Servant.)

Perhaps because he was one of very few voices at the time to speak out against what was going on, Dom Pedro was idolised by many of his parishioners. I saw several people trying to touch the hem of his cassock as he passed them on his way to church, as if he were a living saint. I found it somewhat embarrassing but Dom Pedro seemed unperturbed.

The big landowners hated Dom Pedro with equal passion. If I ever wanted to liven up a boring interview with a landowner, I only had to mention his name. “Brigitte Bardot in trousers” was one of the milder epithets used to describe him.

The landowners’ campaign to have Dom Pedro expelled from the country was vigorously taken up by most of the media. In 1977 Edgardo Erichsen, the director of the powerful Globo TV and radio network, at that time closely allied with the military dictatorship, ended a violent attack on the ‘red’ bishop on television with the following words:

“It seems that the bishop has exchanged his crucifix and rosary for the hammer and sickle, his prayer book for the thoughts of Mao Tse-tung, his priestly piety for violence and that he is only waiting for the right moment to exchange his cassock for a guerrilla’s uniform.”

The Church hierarchy was also unhappy with Dom Pedro. In 1998 he was summoned to the Vatican for an interrogation by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (today Pope Benedict XVI). A head-on confrontation between two colossi of the Catholic faith was how one observer described the meeting.

Throughout his life, Dom Pedro has repeatedly received death threats. On one occasion, a priest that he was travelling with was killed by an irate policeman who thought he was shooting the bishop. Dom Pedro admitted once that he would like to die for the cause:

“I don’t want it to appear evangelical snobbery but, because of the life I’ve led and perhaps because of my temperament, which is a bit radical, I’ve wished ever since childhood to be a martyr.”

But it didn’t happen and Dom Pedro survived. I don’t think it was mere chance: on my recent trip to the Amazon I met a researcher who had been interviewing contract killers. One admitted to him that he’d been offered a great deal of money to kill Dom Pedro. He’d set it it all up but, just before he took out his gun, Dom Pedro turned and looked him straight in the face. “I just couldn’t do it after that”, the killer said.

It is perhaps ironic that it is only now as he approaches death that Dom Pedro has been forced out of the region he has lived in since 1968 and only because of a conflict over indigenous land in which he is not directly involved.

After a long judicial struggle, the Marãiwatsédé indians, part of the Xavante group, won back their old territory in Mato Grosso in the 1990s and finally last year the courts ordered all the farmers, large and small, who were illegally occupying indigenous land to leave by the beginning of January 2013. The story of this indigenous conquest is told on the

LAB website.

Dom Pedro has been a passionate supporter of the Marãiwatsédé cause for decades (the conflict is described in the book he gave me). Although he is too old and too weak to be an active campaigner today, irate landowners blame him for stoking the resistance that eventually led to the indigenous victory and have threatened to kill him. Although unhappy to leave his home, Dom Pedro may well regard this animosity towards him as a badge of honour.

Although he speaks in a faltering voice today, Dom Pedro has lost none of his acuity and his political passion. In a recent interview, he said: “I will never accept this system that is turning humanity into a commodity to be bought and sold.”

I first met Dom Pedro in his home in São Félix in the mid-1970s, when I was writing a book on land conflict in the region. He is a small thin man, and even then he looked frail. What I remember most is the warmth of his welcome, as he invited me into his sitting room in his simple house – not at all the kind of home one expects for a bishop – and started to explain what was going on in the region.

At that time hundreds of peasant families in the region were losing their land to big companies from the south who were setting up large cattle ranches with tax incentives administered by a notoriously corrupt government agency, SUDAM. Despite the isolation of region and the close alliance betwen the justice system and the landowners, some families were valiantly defending their right to stay on their land. There was considerable bloodshed.

There was never any doubt as to which side Dom Pedro was on. Clearly distressed by the scale of the abuses that were being committed against the peasant families and indians, he thrust into my hands a roughly produced booklet – which I have on my desk beside me to today – in which he and other Catholic priests, part of the then influential liberation theology movement, describe in some detail the land conflicts in the region, involving both peasant families and indians, as well as listing the huge sums of government resources that were being channeled to the ranches.

The book was published just after Dom Pedro was appointed bishop in 1971. This was the most repressive period of the military dictatorship and it was dangerous for anyone, including a bishop, to produce such a document, even if semi-clandestinely. Dom Pedro indirectly acknowledges this in his conclusion where he states: “This injustice has a name: Latifúndio [landed estate] … We hope that no proper-minded Christian will describe this document as subversive. … These pages are the cry of a Church in Amazonia – the Diocese of São Félix in the northeast of Mato Grosso – in conflict with the Latifúndio and threatened by social marginalisation.”

At the same time Dom Pedro was expressing his political views even more explicitly in the poems he was writing. Here, in an extract from one of them, he defiantly defends his right to be ‘subversive’ in the sense he gives the word –something that was potentially very dangerous in those days:

“I encourage subversion against Power and Money.

I want to subvert the Law

that turns the people into a flock of sheep

and the government into a slaughterer.

(My Shepherd became a Lamb,

My King became a Servant.)

I first met Dom Pedro in his home in São Félix in the mid-1970s, when I was writing a book on land conflict in the region. He is a small thin man, and even then he looked frail. What I remember most is the warmth of his welcome, as he invited me into his sitting room in his simple house – not at all the kind of home one expects for a bishop – and started to explain what was going on in the region.

At that time hundreds of peasant families in the region were losing their land to big companies from the south who were setting up large cattle ranches with tax incentives administered by a notoriously corrupt government agency, SUDAM. Despite the isolation of region and the close alliance betwen the justice system and the landowners, some families were valiantly defending their right to stay on their land. There was considerable bloodshed.

There was never any doubt as to which side Dom Pedro was on. Clearly distressed by the scale of the abuses that were being committed against the peasant families and indians, he thrust into my hands a roughly produced booklet – which I have on my desk beside me to today – in which he and other Catholic priests, part of the then influential liberation theology movement, describe in some detail the land conflicts in the region, involving both peasant families and indians, as well as listing the huge sums of government resources that were being channeled to the ranches.

The book was published just after Dom Pedro was appointed bishop in 1971. This was the most repressive period of the military dictatorship and it was dangerous for anyone, including a bishop, to produce such a document, even if semi-clandestinely. Dom Pedro indirectly acknowledges this in his conclusion where he states: “This injustice has a name: Latifúndio [landed estate] … We hope that no proper-minded Christian will describe this document as subversive. … These pages are the cry of a Church in Amazonia – the Diocese of São Félix in the northeast of Mato Grosso – in conflict with the Latifúndio and threatened by social marginalisation.”

At the same time Dom Pedro was expressing his political views even more explicitly in the poems he was writing. Here, in an extract from one of them, he defiantly defends his right to be ‘subversive’ in the sense he gives the word –something that was potentially very dangerous in those days:

“I encourage subversion against Power and Money.

I want to subvert the Law

that turns the people into a flock of sheep

and the government into a slaughterer.

(My Shepherd became a Lamb,

My King became a Servant.)

Perhaps because he was one of very few voices at the time to speak out against what was going on, Dom Pedro was idolised by many of his parishioners. I saw several people trying to touch the hem of his cassock as he passed them on his way to church, as if he were a living saint. I found it somewhat embarrassing but Dom Pedro seemed unperturbed.

The big landowners hated Dom Pedro with equal passion. If I ever wanted to liven up a boring interview with a landowner, I only had to mention his name. “Brigitte Bardot in trousers” was one of the milder epithets used to describe him.

The landowners’ campaign to have Dom Pedro expelled from the country was vigorously taken up by most of the media. In 1977 Edgardo Erichsen, the director of the powerful Globo TV and radio network, at that time closely allied with the military dictatorship, ended a violent attack on the ‘red’ bishop on television with the following words:

“It seems that the bishop has exchanged his crucifix and rosary for the hammer and sickle, his prayer book for the thoughts of Mao Tse-tung, his priestly piety for violence and that he is only waiting for the right moment to exchange his cassock for a guerrilla’s uniform.”

The Church hierarchy was also unhappy with Dom Pedro. In 1998 he was summoned to the Vatican for an interrogation by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (today Pope Benedict XVI). A head-on confrontation between two colossi of the Catholic faith was how one observer described the meeting.

Perhaps because he was one of very few voices at the time to speak out against what was going on, Dom Pedro was idolised by many of his parishioners. I saw several people trying to touch the hem of his cassock as he passed them on his way to church, as if he were a living saint. I found it somewhat embarrassing but Dom Pedro seemed unperturbed.

The big landowners hated Dom Pedro with equal passion. If I ever wanted to liven up a boring interview with a landowner, I only had to mention his name. “Brigitte Bardot in trousers” was one of the milder epithets used to describe him.

The landowners’ campaign to have Dom Pedro expelled from the country was vigorously taken up by most of the media. In 1977 Edgardo Erichsen, the director of the powerful Globo TV and radio network, at that time closely allied with the military dictatorship, ended a violent attack on the ‘red’ bishop on television with the following words:

“It seems that the bishop has exchanged his crucifix and rosary for the hammer and sickle, his prayer book for the thoughts of Mao Tse-tung, his priestly piety for violence and that he is only waiting for the right moment to exchange his cassock for a guerrilla’s uniform.”

The Church hierarchy was also unhappy with Dom Pedro. In 1998 he was summoned to the Vatican for an interrogation by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (today Pope Benedict XVI). A head-on confrontation between two colossi of the Catholic faith was how one observer described the meeting. Throughout his life, Dom Pedro has repeatedly received death threats. On one occasion, a priest that he was travelling with was killed by an irate policeman who thought he was shooting the bishop. Dom Pedro admitted once that he would like to die for the cause:

“I don’t want it to appear evangelical snobbery but, because of the life I’ve led and perhaps because of my temperament, which is a bit radical, I’ve wished ever since childhood to be a martyr.”

But it didn’t happen and Dom Pedro survived. I don’t think it was mere chance: on my recent trip to the Amazon I met a researcher who had been interviewing contract killers. One admitted to him that he’d been offered a great deal of money to kill Dom Pedro. He’d set it it all up but, just before he took out his gun, Dom Pedro turned and looked him straight in the face. “I just couldn’t do it after that”, the killer said.

It is perhaps ironic that it is only now as he approaches death that Dom Pedro has been forced out of the region he has lived in since 1968 and only because of a conflict over indigenous land in which he is not directly involved.

After a long judicial struggle, the Marãiwatsédé indians, part of the Xavante group, won back their old territory in Mato Grosso in the 1990s and finally last year the courts ordered all the farmers, large and small, who were illegally occupying indigenous land to leave by the beginning of January 2013. The story of this indigenous conquest is told on the LAB website.

Dom Pedro has been a passionate supporter of the Marãiwatsédé cause for decades (the conflict is described in the book he gave me). Although he is too old and too weak to be an active campaigner today, irate landowners blame him for stoking the resistance that eventually led to the indigenous victory and have threatened to kill him. Although unhappy to leave his home, Dom Pedro may well regard this animosity towards him as a badge of honour.

Although he speaks in a faltering voice today, Dom Pedro has lost none of his acuity and his political passion. In a recent interview, he said: “I will never accept this system that is turning humanity into a commodity to be bought and sold.”

Throughout his life, Dom Pedro has repeatedly received death threats. On one occasion, a priest that he was travelling with was killed by an irate policeman who thought he was shooting the bishop. Dom Pedro admitted once that he would like to die for the cause:

“I don’t want it to appear evangelical snobbery but, because of the life I’ve led and perhaps because of my temperament, which is a bit radical, I’ve wished ever since childhood to be a martyr.”

But it didn’t happen and Dom Pedro survived. I don’t think it was mere chance: on my recent trip to the Amazon I met a researcher who had been interviewing contract killers. One admitted to him that he’d been offered a great deal of money to kill Dom Pedro. He’d set it it all up but, just before he took out his gun, Dom Pedro turned and looked him straight in the face. “I just couldn’t do it after that”, the killer said.

It is perhaps ironic that it is only now as he approaches death that Dom Pedro has been forced out of the region he has lived in since 1968 and only because of a conflict over indigenous land in which he is not directly involved.

After a long judicial struggle, the Marãiwatsédé indians, part of the Xavante group, won back their old territory in Mato Grosso in the 1990s and finally last year the courts ordered all the farmers, large and small, who were illegally occupying indigenous land to leave by the beginning of January 2013. The story of this indigenous conquest is told on the LAB website.

Dom Pedro has been a passionate supporter of the Marãiwatsédé cause for decades (the conflict is described in the book he gave me). Although he is too old and too weak to be an active campaigner today, irate landowners blame him for stoking the resistance that eventually led to the indigenous victory and have threatened to kill him. Although unhappy to leave his home, Dom Pedro may well regard this animosity towards him as a badge of honour.

Although he speaks in a faltering voice today, Dom Pedro has lost none of his acuity and his political passion. In a recent interview, he said: “I will never accept this system that is turning humanity into a commodity to be bought and sold.”