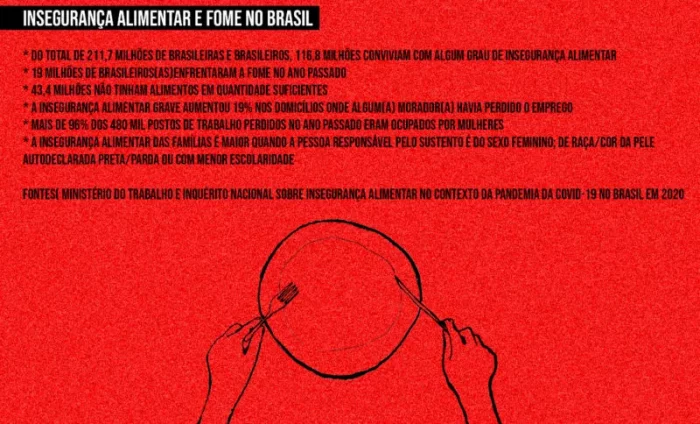

- Single mothers who raise their families alone were hit face on by the loss of jobs and income; women are always the last to eat

- This article was first published here in Portuguese by Agência Pública and translated to English by Matty Rose from the Latin America Bureau.

- You can also subscribe to the biweekly Agência Pública newsletter in English here.

It was around 11 o’clock when Letícia dos Santos, 32, a resident of the Nova Esperança occupation in Jardim São Luís, located in São Paulo’s Zona Sul (South Zone), started making breakfast for her four children that she raises on her own. As the oil in the pain heated up, Letícia mixed together some flour, water and sugar. The smell of fried food that wafted through the shack was reminiscent of a bolinho de chuva donut. Letícia, however, was a few ingredients short: ‘I don’t have any eggs, yeast, milk or cinnamon’, she said.

That day, the family’s meals came from donations. Ever since she lost her job as a carer for the eldery in the middle of the pandemic, Letícia has depended upon donations in order to feed her children. She also does odd jobs here and there, such as making sweets or working at events, in order to cobble together some kind of income.

In 2020, the year in which Letícia was left unemployed, more than 96 per cent of job losses in Brazil were suffered by women, many of them single mothers. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 11.5 million mothers raise their children alone in Brazil. It is in these homes that food insecurity is at its most serious, precisely because women have been the most affected by unemployment and lack of income during the pandemic, as has been detailed in the National Inquiry into Food Insecurity in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil.

In 2020, according to the inquiry, families supported by women, people who self-identify as black or mixed-race, or people with lower levels of education were those most hit by hunger. In the last year, 43.4 million Brazilians – 20.5% of the population – did not have access to enough food. The percentage of food insecurity is higher among households supported by a single person (66.3%), especially if that person is a woman (73.2%). The inquiry also revealed that 55.2% of Brazilians suffered some level of food insecurity in 2020. Put another way, that’s 116.8 million people without full and continuous access to food.

Mothers’ nutrition an afterthought

Letícia still breastfeeds her youngest child, a three month old baby. Since she suffers from severe anaemia, she should take an iron supplement and have a balanced diet, however her dietary needs always come second to those of her children. ‘Because of my poor diet, my breastmilk is low in nutrients’, she says. With the end of the government’s emergency aid payments, the money that the family receives from the government shrank from 375 reais($67) to 217 reais($39) a month. The money is mostly used to pay for the baby’s nappies and food supplements, which cost 52 reais ($9.30) per can.

A majority of the 260 families that live in the Nova Esperança occupation are led by single mothers. There, they receive basic food parcels that ‘at least guarantee us some rice and beans’, Letícia says. They also don’t have to pay rent, which was previously a drain on her finances. ‘I had to leave my last apartment with nothing but my clothes. They wouldn’t let me take my furniture with me because I was in debt to them’, she recalls.

‘If it weren’t for the basic food parcels, I would’ve gone hungry’, says Zenaide Severina, 40, a neighbour of Letícia. Raising two children alone – a 17-year-old boy and a 3-year-old girl -, she went to live in the housing occupation after her house was declared unsafe for habitation by the Civil Defence in 2020. She did not receive housing benefit and in the same year she also lost her job because of suffering from breathing difficulties, for which she is still waiting for the necessary help in order to claim sick pay.

Zenaide’s youngest daughter manages to get all her meals at the local school. When the children are at home, their mother often only eats once a day. ‘I don’t have the courage to make something for myself and not feed them’, she says. Her youngest doesn’t always want to eat rice and beans several times a day, and when there is nothing else to offer her, Zenaide prepares a milk bottle. ‘When you’re on your own, who are you going to turn to for help? I’ve often asked my daughter’s father for help, but he threatens to take her away from me’.

José Raimundo, a researcher who has studied hunger in the São Paulo municipality since the 2000s, states categorically: ‘a person who only has one meal a day, is a person going hungry’.

When a family does not have the food it needs, even in family homes led by men, ‘women are always the last to eat’, the researcher says. ‘In a family home that is suffering from hunger or is at risk of doing so, women are the first to suffer because they tend to prioritise feeding their children first, and their husbands second. The chance of the woman going hungry is higher than that of the man or the children’, he explains.

In a machista society, Raimundo argues, ‘childcare duties fall primarily upon women, who often find it hard to even get a job, as they are dependent on finding someone to take care of their children’.

Sparse donations, meagre aid

‘Everything is more difficult for women’, Ednalva do Nascimento, 43, laments. Ednalva lives in Piscinão de Ramos, a neighbourhood in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, where she provides for five children by doing odd jobs cleaning houses and washing clothes. Her youngest child is 9 years old, while her eldest is 25, and unemployed.

‘I lost my job shortly before the pandemic. When Covid started, I couldn’t even get any cleaning jobs’, she recounts. The family didn’t go hungry thanks to donations of basic food parcels, however even these are becoming ever more scarce as the pandemic drags on, Ednalva says. ‘I often skip meals in order to feed my children. I only manage to buy fruit, vegetables and meat from time to time’, she says.

For Ednalva, who pays 500 reais($89) in rent per month alone, the promise of the increase in the Auxílio Brasil (Brazil Aid) – created by the Bolsonaro government after it ended the Bolsa Família (Family Allowance) social welfare programme – to 400 reais ($71) is of some help, but is not enough to resolve her problems. ‘It helps but I don’t know what things will be like by the end of the year, because the number of donations is decreasing and there still aren’t many jobs available. I think it’s still going to take a long time for our situation to really improve’.

Empty plates and empty policies

The daily reality of food insecurity impacts the mental health of single mothers in a number of ways. Faced with uncertainty over whether she would be able to support her family, Zenaide has suffered from depression. She has been receiving help in a Centre for Psychosocial Care (CAPS), but even her access to the public healthcare system is complicated by the distance she has to travel for the service and the resulting costs. ‘If I use a bit of money to pay for public transport [to go to the appointment], that makes a different to my bills at the end of the month, so I don’t always go’.

In order to deal with the anxiety attacks she suffers, she tends to a small backyard where she cultivates medicinal plants. She says she didn’t receive the emergency aid during the pandemic, for having been off work, and payments from the National Institute for Social Security (INSS) have yet to be released. ‘I also don’t have the right to access benefits to help pay for gas for the kitchen, because I receive Auxílio Brasil. How can I not be allowed this if I’m unemployed and have a small child?’, she asks.

‘The poor are forgotten about’, Letícia laments. Since she went to live in the housing occupation one year ago, she has tried without success to find places in the nearest local school for her children. ‘It seems like the poorer you are, the harder it is to get things done. They create programmes to help the poor, but the poor don’t get helped.’

Letícia’s view is similar to that of the 2021 DHANA (Human Right to Adequate Food and Nutrition) Report, which looked into the impacts of Covid-19 and the actions and omissions of public authorities in the midst of the health, economic and social crisis. The report raises the issue of ‘budget cuts and the weakening of social programmes directed towards promoting food security in Brazil’, such as the Programme for the Acquisition of Food (PAA), and the Programme for the Construction of Cisterns, of great importance to water security efforts across numerous parts of Brazil, particularly in the semiarid regions.

It is also the view of Tereza Campello, the ex-minister for Social Development and Combating Hunger. For Campello, the impacts of the pandemic could have been softened if the Federal Government had adopted measures that strengthened public policy programmes and social protection. ‘Some countries have seen poverty and other issues increase, but they haven’t had their people going hungry. In Brazil we have gone through a dramatic worsening of the situation regarding hunger and varying levels of food insecurity, because whatever social safety net there was that existed before has been dismantled’.

Tereza also recalls how, in the first month of the Bolsonaro government, a Provisionary Measure signed off by the president brought the activities of the Nation Council for Food and Nutritional Security (CONSEA) to an end. Founded in 1993, CONSEA was part of the National System for Food and Nutritional Security (SISAN), and was a vital space for guaranteeing the participation of civil society groups in discussions about access to food.

‘By dismantling CONSEA, Bolsonaro swept away any kind of social oversight of public policies. CONSEA was a really active body, not only in monitoring and overseeing the Federal Government’s activities to ensure the good implementation of public policies, but also by helping to build a solid social policy. When CONSEA was abolished, the whole agenda about transparency and social oversight was thrown into disarray’, Tereza explains. ‘This government doesn’t care about healthy eating, and if that weren’t enough, it also doesn’t care about hunger’, she says.

All images: José Cicero, Agência Pública

This report was originally published in Portuguese by Agência Pública.