On 5 November 2015, the Fundão tailings dam, at the Complexo do Germano iron ore mine in Minas Gerais, collapsed, wiping out the towns of Bento Rodrigues, Paracatu de Baixo and others in the area with a tidal wave of toxic mud. 19 people were killed and entire Rio Doce was contaminated beyond recovery.

The mud travelled 620 kilometres downstream and reached the Atlantic Ocean.

On 25 January 2019, Dam I, at the Córrego de Feijão iron ore mine, also in Minas Gerais, collapsed, killing almost 300 people and devastating the town of Brumadinho. It is estimated that around 26 communities, including indigenous communities and quilombolas have been affected.

The Complexo do Germano mine was operated by Samarco, owned by Vale, the giant of the Brazilian mining industry, and BHP, an Anglo-Australian mining company. Córrego de Feijão is also owned by Vale. In the case of the Complexo do Germano, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office observed that ‘the deaths, as well as the collapse of the dam and the floods, were entirely predicted by the mining companies, but the risks were ignored in an environment that values other factors, such as the increase in profit.’

In April 2022 I met Monica Dos Santos, from Bento Rodrigues, and Marina Paula de Oliveira, from Brumadinho, at a meeting organized by LAB partner the London Mining Network. They were in London to attend the final hearing of a court case that has been brought against BHP in London. They hope that the British court system will be more effective than the Brazilian one, and that, as Marina said, ‘here it’s different from Brazil, where money corrupts whoever has the power to make decisions.’

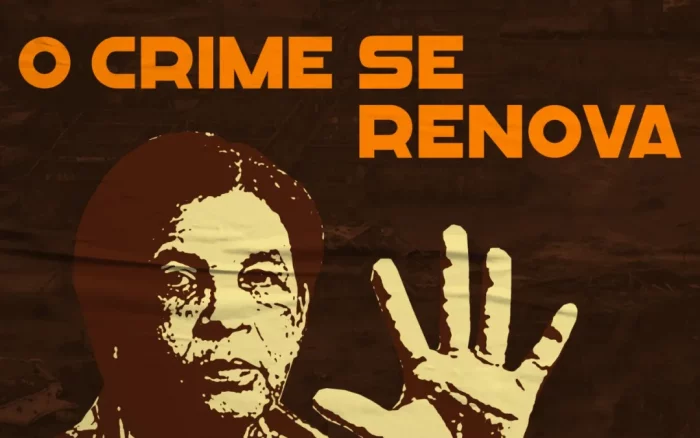

Their crime continues to kill us

Over the last 6 years, that crime has been repeated and has continued to kill us bit by bit.

Monica Dos Santos, from Bento Rodrigues

They made it clear that the impacts of these dam collapses have reached far beyond even the initial death toll. Monica said that the ‘crime was not confined to what happened on 5 November’, explaining how, ‘over the last 6 years, that crime has been repeated and has continued to kill us bit by bit. In the last 6 years and 5 months 82 people have died, of which 44 were from my community alone. Never have so many people died.’ Marina pointed out studies that have been released, showing conclusively that the blood of children and adults in the area contains heavy metals. Yet the communities have received no support to deal with this.

A pamphlet published by Cáritas, who are working with those affected by the two dam collapses, states that ‘the water supply of 4 million people is at risk in the greater area of Belo Horizonte and 30 per cent of the water resources in the city are compromised, according to data provided by the ANA, the National Water Agency. The remaining 70 per cent of the Belo Horizonte supply comes from the Basin of the Rio das Velhas, itself still threatened by 3 dam complexes … currently all these dams have presented a problem or risk, according to the National Mining Agency.’ 1)Cáritas Brasileira Regional Minas Gerais and Iglesias y Minería,(2019), Myths and Uncertainties: The chaos of (non) reparation of crimes perpetrated by mining companies in Brazil.

People are still displaced from their homes, unable to farm the land, and rates of depression and suicide have increased exponentially. This is just a brief overview of impacts that are far reaching, profound and complex.

Six years on from the Fundão collapse, and three years after the Córrego de Feijão collapse, Monica and Marina’s communities are still fighting for reparations. By contrast, in 2019, Samarco was permitted to restart their operations, and in 2021, Vale recorded its highest ever profits.

Monica and Marina’s testimonies expose the evasive, calculating tactics used by the mining companies when it comes to providing (or not providing) reparations. While reports of large sums of money and huge recovery efforts fly around, the lived experience of the communities affected by these crimes tells a very different story. As Marina put it, ‘we are living through a process of reparation full of traps and the violation of rights.’

Renova, the companies’ shield

The natural place to begin untangling the web woven by Vale, BHP and its associates is the Renova Foundation, established to deal with the aftermath of the Fundão collapse. It was set up by Vale and has therefore been accused of acting as ‘an artifice, to shield the mining companies’, created ‘without consulting with and without the participation of the affected communities.’ 2)ibid.

Marina succinctly summarized the fundamental structural flaw implicit in the Renova foundation: ‘Vale does not have the right to sit on the table with us, the affected communities, the victims and look us in the eyes and talk to us as if everything is ok. They murdered people. They committed a crime. They should be treated as criminals. What happens in Brumadinho is: they break the law, commit a crime and they are the ones heading the actions for damages and reparations’.

Renova clearly acts in the interests of its founders. Leticia Aleixo, of Cáritas, who accompanied Marina and Monica in London, says that her organization analysed the accounts of the Renova Foundation in 2019, and even though ‘at that time 4 years had passed and they had spent almost RS$10 million … not even one house was ready.’ It seems the money had gone on buying land and paying lawyers. They also spent R$28 million on communications, including ‘R$17.4 million on a single contract with the aim of promoting a positive image of Renova and its parent companies across the Brazilian media.’

Recognition of victims

On the other hand, people affected by the dam collapses have had to battle even to be recognized as victims and access basic compensation. By April 2021, Renova had received 83,838 applications from those affected by the Fundão collapse. It had accepted only 31,712 of these, 38% of the total and only 11,121 had actually received any compensation.

Since the collapse of Fundão, Vale has been paying the rent of those whose homes were destroyed in Bento Rodrigues. They were supposed to finish building new houses in 2019, but in 2022, they have delayed this deadline three times. Monica told me ‘in my community almost 300 homes need to be built, 47 are ready but these are 47 that no one can move into.’ She said that the houses all have structural problems and could fall down within a few years. When they take this issue to the companies ‘they ignore us, and say that before they hand them over, they will go through a checklist, but this will also just be superficial. It’s the same thing they did with the dam – they knew about the problem, but they preferred not to spend money fixing it.’

Renova also seems to be selective about who it considers to be in need of rehoming. At the LMN meeting, Leticia explained that while the mining companies have committed to the collective rehousing of Bento Rodrigues on a new site, in other towns, located right downstream of the dam, they have only removed around 5 families and told the rest that they can stay, despite their location being threatened by 3 other dams. According to Leticia ‘they don’t say whether or not the mud is toxic, they just reclaim small sections for the families to start planting again. That way, they [claim to] have done their bit, but people still can’t plant, their animals are dying and they are going hungry.’ This tactic allows the companies to limit the amount of land they have to buy and the amount of housing they have to provide.

Skimping on payments

As with housing provision, access to financial aid has also been made into a process full of snares. Since the Fundão dam collapse, the mining companies have been paying an amount equivalent to a monthly minimum wage to everyone who lost their income source due to the collapse, plus 20% per dependent. However, this system excludes many whose work is informal and does not come with accompanying official paperwork, a bracket into which many women and indigenous people fall. Even this aid is reluctantly given: In July 2020, at the height of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, Renova unilaterally cancelled the aid to 7,000 subsistence fishers and farmers, arguing that conditions had been re-established for them to return to their former activities. The courts disagreed and forced Renova to reinstate the payments, though since January 2021, the value has been cut by half for these groups.

In Brumadinho, at the behest of the courts, Vale guaranteed a monthly minimum wage for one year to all residents of Brumadinho (half that for teenagers, a quarter for children). Campaigners managed to get this aid extended. However most residents received half the original amount from November 2019, because they were deemed ‘not to have been directly affected’.

Reparation behind closed doors

Larger financial agreements have also been reached, and again, true accountability and reparations have not been achieved. In February 2021, in the wake of Brumadinho, Vale signed a R$37.7 billion agreement with the state of Minas Gerais ‘the largest agreement of its kind in Latin American history’ 3)Caritas, ibid.. Presented as reparations, this agreement was reached without the participation of the affected communities.

Marina explained how ‘not only were we not allowed to participate, it was a closed process, so we only got to hear about what had been agreed for our own reparations, to repair our lives, through the media.’

Instead of going to the communities, a large part of this money is being spent on infrastructure, such as building a ring road, a bridge and expanding the urban metro system in Belo Horizonte. Marina pointed out that these projects actually ‘benefit the continuation of mining in our state’, meaning that ‘we are seeing the money that was supposed to go to our reparations go to projects that firstly, are going to benefit mining, and secondly, are going to impact and dispossess other communities.’

She denounces the fact that, because they were excluded from negotiations, they were unable to intervene and demand that instead of a ring road, they spend the money on, for example, ensuring water security or investing in projects that would help the state overcome economic dependance on mining.

Meanwhile, no money has been assigned to prevent another dam collapse. The most progress that has been made has been a law with limited reach that passed through Congress in 2020, banning the construction of new tailings dams and giving companies until February 2022 to decommission any dams that are in use. Unfortunately, for many at risk communities, this has resulted in displacement, which companies find easier than actually repairing or decommissioning dams.

A small portion of the total sum agreed has been allocated for use by the affected communities, and the people of Brumadinho have put together a proposal for how they wish their portion of the money to be spent. However, the government is putting together a parallel proposal which the community fear will be selected instead of theirs, as it could be considered more ‘legitimate’ and their own ability to identify what they need could be undermined. Marina and her community are seeking the support of international organizations for their proposal, so as to give it more ‘legitimacy’ in the eyes of the court.

The lack of action to regulate and limit mining is extremely dangerous, and the lack of justice for those affected by the crimes of Vale, BHP and Samarco is proof of a broken system which threatens the existence of many more communities and ecosystems. As Monica and Marina pointed out at the very start of our meeting, their communities were not the first and nor will they be the last. For Marina, ‘When we talk about fair and just reparations, we don’t just mean in terms of value, money. We want something to actually be done, so that this doesn’t happen again. It only happened in Brumadinho because no one was found guilty [for what happened three years earlier] in Mariana.’

Main Image: Bento Rodrigues. Photo: Marcela Nicolas (@marcelanicolass) and Guilherme Frodu (@guifrodu) / Cáritas MG