‘Ipereğ’ayũ’ means ‘I am strong, I know how to protect myself’ in the indigenous Munduruku language, and it is also the name of one of the numerous resistance groups that have been set up by the Munduruku to defend their lands and their people.

The Munduruku, whose name translates as ‘red ant warriors’, an allusion to their fierce battle tactics, are an Amazonian tribe made up of 14,000 people, most of whom inhabit the sparsely populated region of the Tapajós river basin, located in the state of Pará in northern Brazil, an area they have occupied for hundreds of years. For them, the river constitutes the essence of life. Though official maps label the Tapajós and its tributaries separately, the Munduruku regard them as a single river, the Idixidi. They depend on its water for fish, feeding livestock, bathing and transportation. It is also culturally and spiritually important to the tribe.

But in recent years, the river has come under increasing threat due to extensive illegal gold mining in the area. After the fall of the price of rubber in the late 1950s, the Tapajós region was discovered as a major source of gold. Following the construction of the Transamazônica (Trans-Amazonian highway) in 1972, the gold rush intensified and garimpeiros – illegal gold miners – began arriving in large numbers on the Tropas River in the Tapajós basin in the 1980s.

They were driven out by the Munduruku, but returned in 2010, invading land occupied by 21 indigenous riverside communities. After repeated protest from the Ipereğ’ayũ Movement, the federal authorities raided a few mines in May 2020, destroying some mining equipment, but the government has largely failed to act.

Poisoned generations

The struggle of the Munduruku against garimpo is about much more than just a fight for land or resources.

Erik Jennings is a neurosurgeon at the hospital in Santarém, who has worked extensively with the Munduruku. Jennings became concerned after observing some strange neurological symptoms in children from local Munduruku and ribeirinho [traditional riverside] communities, including an unusual number of children requiring wheelchairs, delayed psycho-neuro-motor development and high rates of failure in the local schools. For Jennings, these all pointed to one thing: mercury poisoning.

Mercury has been used for centuries as an inexpensive and easy method for collecting gold. Garimpeiros pump it directly into the river where it binds to gold particles, forming an amalgam that sinks to the bottom of buckets or holding ponds where it can be collected. They then burn off the mercury to leave the remaining gold behind, releasing mercury tailings and methylmercury into the water. This then crosses the cell membrane of organisms, contaminating fish, which is an essential part of the Munduruku diet – they often eat it three times a day, nearly every day of the week.

On top of this, garimpo erodes riverbanks, and in the Tapajós region the earth itself contains mercury deposits. New excavators, with destructive power many times greater than methods previously used, dig deep holes along the riverbanks, pluck up riparian forest and dislodge tons of mercury-rich soil into the water. The mercury deposits in the topsoil sink to the bottom of the river, where deprived of oxygen, they react with bacteria, becoming methylmercury.

Alessandra Munduruku, tribe leader and activist, says ‘We know we are sick, we know we have mercury in our bodies. But it is the only source we have, we can’t stop eating the fish because it’s full of mercury. If we did, everyone would starve because most of us depend on the river and the fish to survive.’

Inhabitants of the Tapajós River Basin have been regularly tested for mercury contamination by healthcare professionals since the 1990s. A recent study undertaken by WWF and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) showed that, of the 200 indigenous people evaluated, all research participants had traces of mercury in their bodies, and in over of half of them, contamination levels were well above what is considered safe.

More worrying still, in the villages right on the banks of the Tapajós, it was found that four out of ten children under the age of five had high concentrations of the metal in their bodies.

LAB spoke with Jorge Bodanzky, an acclaimed Brazilian documentary filmmaker, who is currently producing a film in collaboration with Jennings and the Munduruku about the mercury contamination in the Tapajós.

Entitled The Amazon: a new Minamata?, the film draws a parallel with the Minamata disaster in Japan, in which thousands of people were poisoned after consuming mercury-contaminated fish and shellfish from the Minamata Bay. A chemical factory owned by the Chisso Corporation was identified as the cause; it dumped industrial wastewater into the bay over several decades.

‘Everything that happened in Minamata has started happening in the Amazon,’ says Bodanzky. ‘It’s on a different scale, but we can see what might happen if nothing is done about it.’

The tip of the iceberg

‘The mercury issue is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the great problems facing the Amazon,’ Bodanzky says. ‘The question of public health is just one dimension of a much bigger problem. At its core, the issue is a political one and is about the way in which the Amazon is being occupied and used. We’re talking about a modus operandi that allows indigenous territories and ribeirinho communities to be invaded by garimpeiros.’

In other words, the poisoning of the Munduruku is just one consequence of the aggressive project to colonise the Amazon which started under the military dictatorship. It is also the result of the long offensive against Brazil’s indigenous people, who have faced genocide, land seizure, environmental degradation and exploitation for 520 years.

These two projects, which go hand-in-hand, have massively intensified under Bolsonaro. ‘Where there is indigenous land, there is wealth underneath it,’ he said during his campaign for the presidency in 2017.

Bolsonaro’s government has slashed environmental protections and given explicit encouragement to garimpeiros. It is targeting nature reserves and protected areas, using the Ministry of Environment to destroy legal protections and convert this land – including indigenous territories – into private property.

With Bolsonaro’s own father having participated in the famous Serra Pelada gold rush of the 1980s – the subject of a much-celebrated series of photos by Sebastião Salgado – the garimpeiros see Bolsonaro as their champion. He has defended them against environmentalists, NGOs, indigenous advocates, international leaders and the government’s own regulatory agencies.

Over 3,700 gold mines have opened up in the Tapajós region since 2014. Of these, almost a quarter are in federally protected areas, including indigenous lands and national forests, where mining is prohibited, according to Article 231 of the 1988 Constitution.

As well as turning a blind eye to garimpeiros, Bolsonaro is attempting to legalise industrial mining on indigenous territories. While the Constitution prohibits mining on indigenous lands, this can be overridden with congressional authorisation. In February 2020, Bolsonaro’s administration submitted a bill to Congress that would drop the need for this congressional permission for formal mining concessions. Since the bill was submitted, there has been a surge of new mining applications affecting indigenous territories.

The Sawré Muybu territory of the Munduruku is particularly vulnerable because it has not been fully ratified as an indigenous reserve by the Brazilian government. It is the most recent target of UK-based mining giant, Anglo American, which submitted five applications to mine on Sawré Muybu territory between 2017 and 2019.

In November 2020, InfoAmazônia revealed that up to 27 applications made by Anglo American to mine in indigenous land in Mato Grasso and Pará had been approved by the National Mining Agency (ANM), despite the constitutional prohibition. Of these 27, 13 target the Sawré Muybu land.

Anglo American has since responded, recognising only 25 of these claims, and stating that they have either been withdrawn, ceded to other companies or may turn out not to overlap with indigenous territory, pending revision by the ANM. In the same letter, however, the company announced that it is ‘unable to commit to ruling out ever undertaking mining on indigenous lands in Brazil’.

It would appear that the company is counting on the proposed bill – termed the ‘death bill’ by the Munduruku and other opponents – to be pushed through by Bolsonaro’s government. For now, however, thanks to mounting pressure from the Munduruku and Amazon Watch, Anglo American withdrew its three most recent applications on Sawré Muybu land on 27 January.

Exacerbated by the pandemic

Mining operations have proved all the more troubling in the wake of the pandemic. In June 2020, at the height of the first wave of infection in Brazil, information from the Special Indigenous Health Districts (DSEI) of the Brazilian Amazon showed that the Tapajós River Basin had the highest mortality rate of all indigenous health districts in Brazil. Since May last year, the virus has claimed the lives of 15 Munduruku people, most of whom were elders.

It is likely that the rapid spread of COVID-19 through Munduruku villages in the Tapajós region was at least partly due to illegal gold mining operations in the area. During the pandemic, security forces were no longer deployed to control invasions of traditionally occupied territories and public lands, with the Brazilian government slashing the budget for the environmental protection agency IBAMA by 25 per cent. The garimpeiros did not lock down, but rather have been making the most of the pandemic to further their advances.

Driven by the absence of law enforcement and the soaring price of gold, people are travelling from all over the country to hundreds of illegal mining sites, invading protected indigenous lands, poisoning the rivers with mercury, and bringing coronavirus to otherwise isolated communities. This invasion is almost certainly fuelled by the desperation of marginal people whose traditional sources of income have been destroyed by the pandemic. Much of this activity has been concentrated in under-policed Pará, home to most of the Munduruku.

Bolsonaro’s actions suggest that he sees the pandemic as an opportunity to ‘clear the ground’ in the Amazon to make way for development. Indeed, Ricardo Salles, his Minister for the Environment, was caught on camera at a cabinet meeting in April last year suggesting that the pandemic be used as an opportunity to eliminate environmental protections while the press looked the other way.

Brazil is currently suffering its darkest days of the pandemic and with the numbers going rapidly in the wrong direction, things are set to get even worse. With Bolsonaro allowing the virus to rip the country, while inviting private interests to occupy and despoil indigenous land, the Munduruku face mortal threats on all sides.

‘The indigenous peoples are alone and we have to fight against the virus, the loggers and the wildcat miners. We don’t know which is worse,’ Alessandra Munduruku told The Guardian.

‘We are the Munduruku majority’

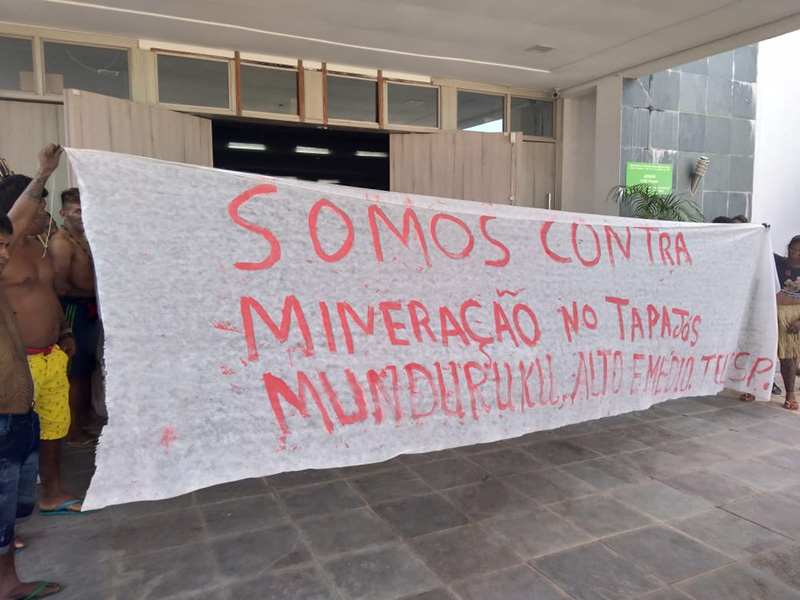

But they will not give up without a fight. They have defended their territory time and time again from illegal miners, loggers, and deforestation, mobilising through road blockades, collective action, official letters, marches and public campaigns.

In an open letter published last October, Munduruku chiefs demanded to be consulted in accordance with the ILO Convention 169, which gives indigenous communities autonomy and the right to decide for themselves on the projects contemplated in their ancestral lands.

They declare, once and for all, ‘We are the Munduruku majority, speaking from our villages in one voice: we are against mining and logging in our territory!’

Main image: Indigenous people, like these Munduruku warriors, have battled for years to gain access to government to better protect land rights and the environment. Reorganization of administrative councils and other government bodies is being used to deny a voice to civil society and environmentalists, according to critics. Image by Mauricio Torres.

Jasmine Haniff is a student at Goldsmiths College, London. As part of her course, she is working with LAB on a series of articles about the impact of mining on bodies of water and their surrounding communities.

See her earlier article here.