- The Brazilian state of Roraima is currently dependent for 70 percent of its power on Venezuela’s Guri hydroelectric dam. But socioeconomic chaos in Venezuela, and deteriorating political relations between the two nations, have caused Brazil to fast-track a 750-kilometer transmission line to replace the imported energy.

- General Otávio Rêgo de Barros, using a national security justification, has announced that construction will begin at the end of June on a powerline running between the cities of Manaus and Boa Vista, connecting Roraima with Brazil’s national electrical power grid.

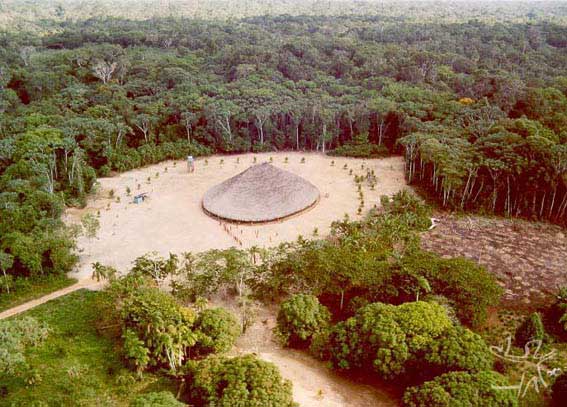

- 125 kilometers of the planned transmission line will run through the Waimiri Atroari reserve, and the indigenous group has long resisted its construction. The Waimiri Atroari are concerned about detrimental impacts on the environment and on wildlife, as hunting is a primary way for their communities to obtain food.

- Roraima state has done viability studies showing that wind and solar power offer cheaper alternatives to the transmission line. But the Bolsonaro administration has ignored those alternatives. “The Indians will be consulted, but national interest must prevail,” said the general.

Brazil’s Bolsonaro government has invoked reasons of national security to push forward on the construction of a long-resisted 125 kilometer (78 mile) electrical transmission line through the heart of the Waimiri Atroari Indigenous Reserve in the states of Amazonas and Roraima.

For years the Waimiri Atroari people have fought government attempts to build the powerline through their territory, demanding compensation and safeguards to protect their way of life and the wildlife they depend on for food. Right-of-way negotiations with federal authorities, including FUNAI, the indigenous affairs agency, IBAMA, the environmental protection agency, and MPF, the federal prosecutors office, have long been ongoing.

But at the end of February, presidential spokesman General Otávio Rêgo de Barros announced that construction of a 750 kilometer (466 mile) powerline to bring energy from Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state, to Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima, Brazil’s northernmost state, will begin on 30 June; 125 kilometers (almost 80 miles) of the line will pass through the indigenous reserve.

The general justified the rush to build by saying that questions of national security override the interests of the Waimiri Atroari and the environment. “The Indians will be consulted, but national interest must prevail,” he said.

Another Bolsonaro minister who preferred to remain anonymous, spelled out the policy’s justification: “The government’s dialogue with the indigenous peoples continues but their permission is no longer a condition for the concession of the license to build.”

The decision was made at a specially convened meeting of the National Defense Council in Brasilia on 27 February. The reasoning behind the project’s fast-tracking: Roraima state currently depends on neighboring Venezuela for 70 percent of its electrical energy needs, power produced by the Guri hydroelectric dam. The new transmission line will end that dependency by connecting the state to Brazil’s national power grid, avoiding potential outages due to current chaotic socioeconomic conditions in Venezuela.

Relations between the two nations became strained in recent months, as Venezuela closed its border with Brazil, and the rightist Bolsonaro government called for the overthrow of Socialist President Nicolás Maduro, while also receiving self-proclaimed Venezuelan president Juan Guaidó in the presidential palace.

Construction of the Manaus to Boa Vista transmission line, which will run alongside the existing BR-174 highway, is expected to take 3 years. The government argues that by running the powerline beside an existing road, it will have little impact on the indigenous territory. But the hundreds of giant pylons needed to carry the heavy electrical cables will require a wide deforested corridor under and around them. Access roads for maintenance will also be needed.

The indigenous community, which relies on the local forest for food, says that deforestation and the disruption of wildlife during and after construction is inevitable. The reserve’s inhabitants also argue that they will suffer the project’s impacts, but not its benefits. When finished, they note, the transmission line will carry electricity overhead, but not provide energy to their indigenous reserve and its villages.

Joênia Wapichana, Brazil’s first female indigenous congresswoman, elected in 2018 for the state of Roraima, said: “There is a court decision that the Indians should be consulted and not put under pressure.… This right to consultation is guaranteed under the [International Labour Organization) ILO’s 169 Convention, which is legally binding in Brazil.” She said that consultations between the Waimiri Atroari and various government agencies over the proposed powerline have been going on a long time.

MPF federal prosecutors have also expressed concern at the government’s decision to fast-track the project without further consultation. They note that the powerline’s location was chosen without considering alternative routes farther away from existing villages.

Joênia Wapichana, Brazil’s first female indigenous congresswoman, elected in 2018 for the state of Roraima, said: “There is a court decision that the Indians should be consulted and not put under pressure.… This right to consultation is guaranteed under the [International Labour Organization) ILO’s 169 Convention, which is legally binding in Brazil.” She said that consultations between the Waimiri Atroari and various government agencies over the proposed powerline have been going on a long time.

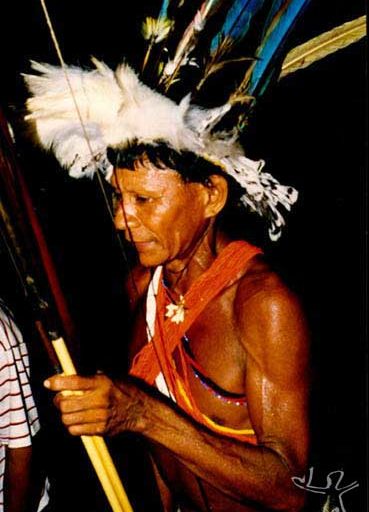

The MPF has worked with the Waimiri Atroari for many years, first filing suit to claim compensation for the wrongful deaths of an estimated 2,000 Indians who perished as a result of an earlier government project, the building of the BR-174 highway linking Manaus to Boa Vista in the 1970s and 1980s. At the time, the ruling military dictatorship was eager to open up the Amazon region via the construction of a new road network, including the controversial Transamazon Highway. The many indigenous tribes blocking the highway’s path were seen as a problem typically solved by largescale removal of the people to other lands, against their will. But in the case of the Waimiri Atroari, the solution was extreme violence.

A survivor recalls: “Helicopters flew over the villages, spilling poison and detonating explosives over hundreds of Indians who were meeting to celebrate rites of passage. White men in uniform attacked those who survived with guns and knives, cutting their throats. Tractors destroyed plantations, trails and sacred places.”

A village of the Waimiri-Atroari presenting six testimonies of their traumatic experiences during the construction of highway BR-174.

Video: TV Em Tempo. 12 March 2019

These attacks, and the communicable diseases that came after forcible contact with outsiders, led to a drastic reduction in indigenous numbers – by 1986 only 374 Waimiri Atroari were left out of an estimated original population of 3,000.

The MPF has not only demanded compensation for the Waimiri Atroari, but also that the government give a guarantee that military intervention in their territory will not happen again, and that any new project touching their land only be built with their consent. Critics say that the Bolsonaro government is using Venezuelan instability as an excuse to proclaim a national security justification, and rush the powerline to completion.

Analysts also note that Bolsonaro’s transmission line decision ignores the possibility of utilizing alternative energy sources. The Roraima government had begun to move forward with a renewable energy plan, based on studies carried out by the federal Mines and Energy Ministry. That research found that the state has an abundance of wind and solar potential due to its proximity to the Equator. It also has rivers that could provide hydroelectric power. Meetings between solar and wind industry representatives and the state governor have already been held.

Many of the Waimiri Atroari view the Bolsonaro administration’s decision to ignore these efficient alternative energy options, and opt instead for the far more costly transmission line, as a declaration of war against them. The dispute will almost certainly end up going to court, and possibly all the way to Brazil’s Supreme Court.

Sidney Possuelo, a respected former head of FUNAI told the Reuters news agency: “The situation of Brazil’s indigenous peoples has never been good. But during 42 years of working in the Amazon, this is the most dangerous moment I have seen.”