Like a latter-day Mussolini 1)Benito Mussolini, Prime Minister of Italy and de facto dictator, from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 1943, and ‘Duce’ of Italian Fascism from the establishment of the Italian Fasces of Combat in 1919 until his execution in 1945 by Italian partisans – Wikipedia. Il Duce was a keen motorcyclist, riding his own machine at the head of rallies, such as the one in Rome in May 1933., President Jair Bolsonaro roars through the streets at the head of a swarm of motorbikers, dressed in black and grinning like a man without a care in the world. Last week it was Rio, this Saturday it will be São Paulo.

The rallies end with Bolsonaro addressing crowds of supporters, unmasked like himself, berating the governors and mayors who are implementing lockdowns in an attempt to stop the spread of the virus, because they are curtailing ‘freedom’.

The CPI, or Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry, now taking place in the Senate has shown that Bolsonaro actually wanted the virus to spread and took every step at his disposal to make this happen. Disparaging vaccines while promoting useless palliatives, replacing doctors with unqualified military officers in the ministry of health, encouraging crowds and refusing to wear a mask, Bolsonaro bet on herd immunity as the solution, even if it meant that over one percent of the population would die. So far almost half a million people have died, and the pandemic is far from over.

100 years ago, when Mussolini began riding around on a motorbike, it was seen as a symbol of power and potency, modernity and dominance. No wonder it appeals to Bolsonaro, who seems to inhabit a parallel world, far from the reality of Brazil. In the Panglossian view he presented in a recent nationwide broadcast, all is well with the economy, the virus is under control, vaccination (which he tried to prevent) is rolling out fast and there’s nothing to worry about.

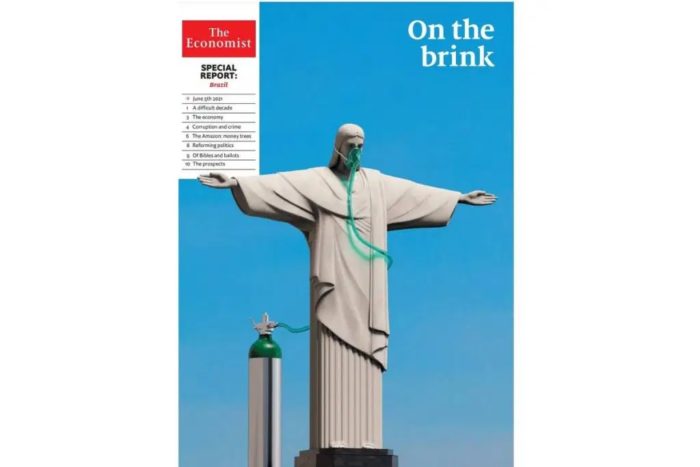

Outside Bolsonaro’s rosy bubble, his government’s failure to act and its incompetence when it does so, have left millions of adults without vaccines, millions of schoolchildren without access to lessons, and millions of jobless and small businesses without relief. When The Economist portrayed the statue of Christ in Rio connected to an oxygen tank and suggested that Brazilians should ‘vote him out’ next year, the communications minister mistranslated this as ‘eliminate him’, and accused the magazine of recommending that Bolsonaro should be killed. Either the minister’s English is very flaky or it was yet another example of fake news.

One man is responsible

In the midst of this plethora of fake news, smoke screens and red herrings tossed out every day to draw attention away from the real news by the president’s sons and followers, the CPI ploughs on, uncovering damning facts and figures about the government’s response to the pandemic, and trying to pinpoint where the responsibilities lie for the relentlessly increasing death toll.

For some commentators the CPI has taken over from BBB (Big Brother Brazil) as the daily entertainment, with histrionic verbal battles between opposition senators and pro-Bolsonaro senators.

–Your Excellency is a liar!

–Your Excellency is an opportunist!

But the investigations point to one man as ultimately responsible, and that man is President Bolsonaro. Senator Tasso Jereissati, of the PSDB, said ‘the responsibility, without a doubt, lies at the President’s door.’ The delay in buying vaccines was deliberate, he believes. This conclusion was reached after evidence from Pfizer’s chief executive in Latin America that he had sent dozens of emails to the Ministry of Health offering vaccines last year, and received not a single reply.

Among the witnesses called by the CPI was former Health Minister Eduardo Pazuello, whose evidence was afterwards described as a tissue of lies. Pazuello also became the focus of a new crisis involving the Armed Forces, when he, a serving general, defied army regulations to appear at Bolsonaro’s motorbike rally in Rio, even addressing supporters from the sound truck.

As serving or ‘active’ officers are banned from taking part in politics, it was expected that the Army High Command would see no alternative but to punish him, even if it meant displeasing their Commander-in-chief, the president. After a week of suspense, the generals buckled and announced that they had accepted Pazuello’s defence, namely that it was only a motorbike rally and not a political event. Bolsonaro’s boast about ‘my army’ seems to have been confirmed.

But not all analysts see what happened in such black and white terms, instead seeing it as the Army choosing the least bad outcome, by not openly confronting Bolsonaro. UFRJ history professor Francisco Teixeira, who has specialized in military affairs, says that while the decision could open the way to anarchy and indiscipline in the barracks, it also generated a feeling of resentment and humiliation which will have consequences.

Preparing for a 21st Century coup?

He also believes that the armed forces will not have a central role in any attempt by Bolsonaro – which many now take for granted – to challenge the result of the 2022 elections if he loses to Lula. He has begun to lay the groundwork for this scenario by questioning the electronic voting machines which have been used in Brazil for over 20 years without complaints and demanding a paper vote instead. History shows that paper votes make fraud easier.

If a coup is needed to overthrow the result, then Teixeira believes it will not be a copy of the 1964 model with tanks in the streets, but more like the 2019 Bolivian coup, which prevented Evo Morales’ victory, or the 2021 invasion of the Capitol in Washington inspired by Trump.

Instead of the armed forces, Bolsonaro will count on the state military police forces, numbering 430,000, and private security guards, who total 350,000. This militia force, totalling almost 800,000 armed members, is largely pro-Bolsonaro and outnumbers the 300,000 regular troops.

Those that disagree with this analysis say there is no need for a coup of whatever sort, because it is the military who already run the government, and who will dump Bolsonaro, motorbike and all, if he becomes too inconvenient. Look what happened to Mussolini.

Meanwhile Bolsonaro’s agenda is already geared to the election, not the pandemic. He has no time for lamenting the 480,000 dead, visiting hospitals or talking to health workers. Instead he travels up and down the country inaugurating bridges and roads, most of them the work of previous governments that have already been opened previously. In the Amazon he even opened an 18-metre long bridge, for want of anything more impressive, and insisted on setting foot inside the reserve of the Yanomami – not to promise an end to the recent attacks by garimpeiros (wild-cat miners), but for a photo-op in a feathered headdress. He later referred to the ‘Balaio’ indians, a people who do not exist, and said their herbal teas cure Covid-19.

The threat of Lula

The President has been galvanised into action by the reappearance of Lula on the political scene, and the polls which show the PT candidate winning next year’s presidential race.

Bolsonaro’s latest vote-catching ploy is to bring the Copa America soccer tournament, to which both Argentina and Colombia have refused to play host, because of the health risks, to Brazil, without consulting clubs, teams, or players. Although the matches will take place in stadia without fans, the tournament involves thousands of people, including press and technical teams. Anyone who protests, even Tite, the Brazil team coach, is immediately dubbed a ‘communist’ by one of the Twitter-itchy Bolsonaro sons. The Supreme Court will meet in emergency session on Thursday to consider an attempt by a political party to have the tournament, due to begin on Sunday, suspended for health reasons. A new national protest on 16 June hopes to repeat the resounding success of the first one on 29 May, which brought hundreds of thousands on to the streets. Nobody will be riding a motorbike.

Main Image: Bolsonaro riding in a motorcycle cavalcade. Image: Yahoo/Al Jazeera

References

| ↑1 | Benito Mussolini, Prime Minister of Italy and de facto dictator, from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 1943, and ‘Duce’ of Italian Fascism from the establishment of the Italian Fasces of Combat in 1919 until his execution in 1945 by Italian partisans – Wikipedia. Il Duce was a keen motorcyclist, riding his own machine at the head of rallies, such as the one in Rome in May 1933. |

|---|