Main image: Without water, the virus spreads. Image: Facebook profile of Barrios de Pie

Ramona Medina, one of the community leaders of Villa 31, a Buenos Aires villa miseria, has died from coronavirus after constantly denouncing the lack of water and the conditions for maintaining social distancing measures in her neighborhood. Ramona appeared on various media to raise awareness about the inhuman conditions that her family and neighbors were exposed to during quarantine.

We have been without water for eight days now and they ask us to maintain hygiene, not to go outside.

‘Here I am, trying to find an answer to everything that Santilli [deputy mayor of Buenos Aires] says about us having water, [when he says] that everything is resolved. We have been without water for eight days now and they ask us to maintain hygiene, not to go outside. How do you expect us not to go outside if I have to go and buy water?’, protested Ramona.

Ramona Medina from Villa 31 denounces the failings of the Larreta city government. Video: El Explicito, YouTube, 3 May 2020.

Despite being in an at-risk group because she suffered from diabetes and had a daughter with multiple disabilities, she received no help from the government, which didn’t even respond to her protests. After 12 days without mains water she was diagnosed the COVID-19 and died after three days in hospital. Ramona is not an exception, there are many similar stories behind the numbers.

Villas miseria

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the great inequalities within Argentine the society. The severity of the outbreak of the virus in shanty towns of Buenos Aires is a result of social injustice and enormous disparity between the rich and the poor in access to civic rights and opportunities. The most disadvantaged have experienced the greater impact of the virus, not because of the lack of immunity, but because of the long-standing absence of political interest in reducing this gap as well as the lack of a comprehensive response to the crisis which would include all social groups. Government strategy has failed to take into consideration the 30 per cent of population who live below the poverty line and have no capacity to adopt preventive measures.

In Argentina, ‘villa’ does not imply a luxury dwelling, but its very opposite. There are 4,416 informal settlements, commonly called villas miseria or asentamientos de emergencia. These areas are inhabited by the most impoverished members of society who have no access to housing through the formal real estate market. Most of the villas share: a lack of infrastructure and access to basic services – no mains water (89%), no electricity (68%), no mains sewage (98%), no gas (99%); high population density – the makeshift houses are often home to several families; and most residents are either unemployed or rely on the informal job market. Buenos Aires accounts for almost half of the villas, which total 485,080 families in the province and 73,673 within the city boundaries.

Social Determinants of Health

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health as ‘the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age’, which are largely governed by the distribution of power and resources within society. Susceptibility to the virus infection and the level of exposure among different social groups depends to a great extent on socio-economic factors which define the welfare status of individuals, such as ‘safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free from life-threatening toxins’. The lower the welfare status, the greater the susceptibility and exposure to the viral infection.

It is coronavirus that decides to put the elderly at risk, but it is not the virus which decides to put at risk the poor, as a group.

Of the total number of 16,984 people infected with COVID-19 in City of Buenos Aires, 40% occur in villas despite the fact that their inhabitants constitute only 15% of the population. Ignacio Levy, an activist from Villa 31 claims that ‘Corona virus decides to put the elderly at risk, but corona virus does not decide to put the poor, as a group, at risk’. This is a domain of public policy informed by the neoliberal values of Structural Adjustment Programs which are based on the underfunding of public services. For example, the Social Voucher allowance (1,100 pesos per person) in Buenos Aires was paid to 70,022 people in 2009 and in 2019 to just 4,874.

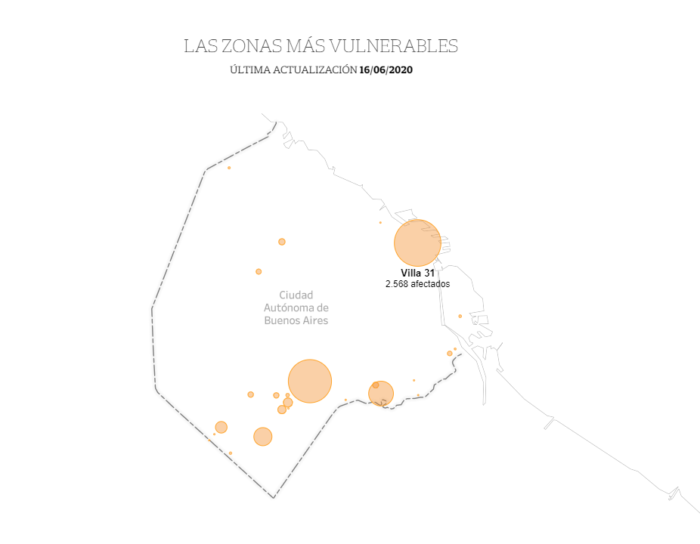

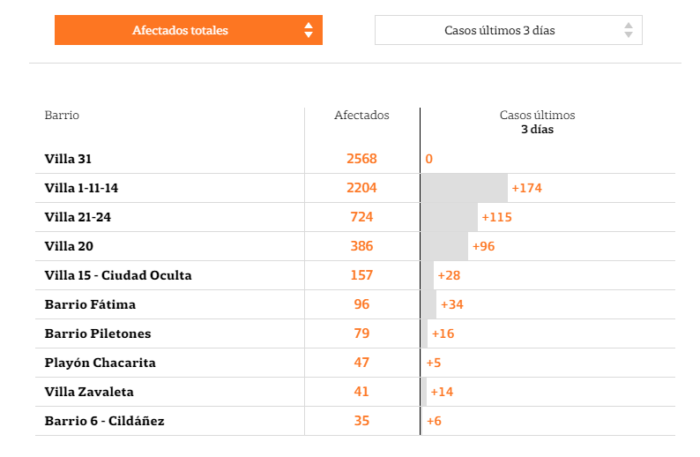

The most vulnerable areas from 17 June 2020. Elaborated from La Nacion

Government preventive recommendations include social isolation, social distancing (2 meters), wearing a mask outside the house, regular hand- cleaning, regular sanitizing of objects in frequent use and house ventilation. These regulations may be reasonable for residents of Belgrano or Palermo, where many people can work from home and have money to survive through months of isolation. In popular neighborhoods people do not have this privilege as most rely on the informal economy and receive no social protection. To earn money they have to leave their homes. Without access to mains water they cannot easily wash their hands. Although access to water is a basic human right, Argentina has no laws regarding its supply. In Buenos Aires about 15% of the population lacks this right and has no legal mechanism to claim it.

Food banks stretched to the limit

Agustin Navarro, a community activist from Barrios de Pie organization, died after being infected while serving at the food bank in Villa 31. Shortly afterwards, Carmen Canaviri, from the same organization, died while serving at a food bank in Villa 1-11-14. The government-supplied rations are not enough for the number of families: of the 63 communal kitchens in popular neighborhoods, 42 are not receiving any food supplies from the government, let alone the wages for their workers, who risk their lives every day to help others. The food emergency was affecting the villas long before the virus and during the lockdown the number of people attending food banks has grown substantially. For example, El Dari kitchen in villa 21-24 before the pandemic was serving daily 300 portions and the total has now reached 1,970.

The mayor of Buenos Aires, Horacio Antonio Rodríguez Larreta, has been instructed by judge Elena Liberatori to provide communal kitchens with more food, hygiene products and also insect repellent to deal with the increasing number of cases of dengue. A study carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC) shows that in the third quarter of 2019, there were 595,000 people below the poverty line and 169,000 below the extreme poverty line in the City of Buenos Aires. According to the Ministry of Human Development, the governments allocations are sufficient for a mere 101,673 people.

Education under lockdown is another area where government responses have not been tailored to the reality of the poor neighborhoods, where 70% of children have no access to a computer and 83% cannot connect to the internet. 85% of children did not receive any printed exercise books. Again, Larreta was ordered by a judge to provide all villas with internet and students with computers or tablets to give them equal opportunity to continue their education during the lockdown.

The emergence of the new poor

Covid-19 is clearly a social virus. Pandemics in the past have tended to spread most widely and have the harshest effects among the most disadvantaged social groups. as happened with the Spanish Influenza in 1918-20. While no vaccine for this new virus has yet been discovered, the most effective way to fight a pandemic is to understand the nature of the virus and identify and promote behaviours that prevent it from spreading. Those who are lack the means of adopting preventive measures should be at the forefront of government response.

Although the government anticipated that virus would reach the shanty towns, little or nothing has been done to prevent that from happening. But for the largely voluntary work of non-governmental organizations, community and religious groups and the solidarity of neighbours, the pandemic could destroy entire communities.

Meanwhile, the virus has caused many people to fall into the poverty. The neighborhood of La Boca, found itself in a dilemma – the number of those infected was growing, yet the government was not delivering any help to the habitants because this district is not recognized as vulnerable. La Boca has always been on the borderline of ‘vulnerable’ status and years ago was been declared to be in climate and urban emergency. Due to the lockdown many families have lost their source of income. The community also demanded special preventive measures for conventillos – tenements where multiple families share kitchen and yard space. Viral exposure is much stronger where multiple families need to share common areas.

The city and national Ministries of Health together launched the Detectar project, which organizes the active search and trace for Covid-19 cases by neighborhoods using door-to-door questionnaires to identify symptoms and transporting all who present any symptoms to a testing center. Anyone who was in contact with these persons in the last 48 hours, has to self-isolate for 14 days. However, this will not be enough to defeat the pandemic. To achieve that the government must address the social, economic and political factors that shape structural poverty and provide citizens with the resources that will enable them to comply with preventive measures.

The UN forecasts an economic collapse in Argentina after the pandemic, yet it is hard to imagine that living conditions will be allowed to further deteriorate in the villas. Perhaps the pandemic could provide an opportunity to settle accounts with the 10% of the population who account for more wealth than the remaining 90 per cent of Argentinians, by making them pay back their outstanding debt to democracy. If they fail to do so, the consequences may be dire.