Faith and large-scale mining have something in common: they both move mountains. On many occasions, the Church has been an obstacle to industry’s efforts to expand into Latin American countries. A growing movement links spirituality, environmental struggles, and resistance to large-scale mining. The first message Pope Francis gave minutes after arriving in Brazil some months ago was: “I don’t have silver or gold, but I bring with me the most precious gift: Jesus Christ!”

On September 7 this year, the Pope convened a ‘Day of Reflection’ at the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, attended by representatives of the mining industry. In his letter to them, he stated: “…so as not to repeat grave errors of the past, decisions today cannot be taken solely from geological perspectives or the possible economic benefits for investors and for the states in which the companies are based. A new and more profound decision-making process is indispensable and inescapable, one which takes into consideration the complexity of the problems involved, in a context of solidarity. Such a context requires, first of all, that workers be assured of all their economic and social rights, in full accordance with the norms and recommendations of the International Labour Organization. Likewise it requires the assurance that extraction activities respect international standards for the protection of the environment. The great challenge of business leaders is to create a harmony of interests, involving investors, managers, workers, their families, the future of their children, the preservation of the environment on both a regional and international scale, and a contribution to world peace.”

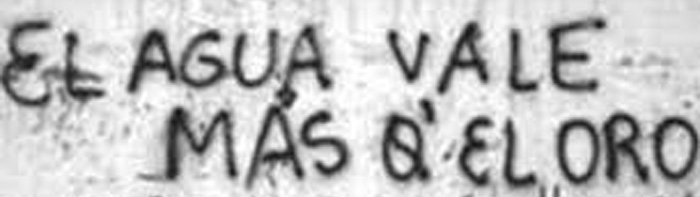

T-shirt Slogans

T-shirt Slogans

On November 12, Pope Francis posed for a photograph with a t-shirt that stated, “Water is more precious than gold.” He has posed holding many other t-shirts before, like the one of his beloved football team San Lorenzo de Almagro in Buenos Aires. But this time it got much more attention, at least within the environmental movement. The photographs were taken after Pope Francis met with a group of Argentine environmental activists in the Vatican to discuss large-scale mining and other controversial extractive industry practices. He reportedly told the group he is preparing an encyclical about nature, society, and environmental pollution.

In a recent blog post, Keith Slack, Global Program Manager of Oxfam America’s Extractive Industries Campaign, discussed the “Day of Reflection” that convened in September by the Vatican’s Pontifical Council on Justice and Peace. The gathering meant to provide “an opportunity for constructive review of key mining-related issues and to identify concrete actions that would make a positive difference in the future.” Industry leaders were among the gathering’s participants, including CEOs of Newmont, Anglo American, and Rio Tinto. Other participants included Oxfam America’s president, representatives from Catholic NGOs, and clergy from different parts of the world.

“For the Vatican,” says Slack, “mining conflicts are a social issue it can’t ignore, especially given the high-profile role played by some of its clergy in them.” The issue is not new: Mineweb editor Dorothy Kosich raised a provocative question back in April 2005: will mining survive a Latin American Pope? From the outcome of the Vatican’s “Day of Reflection,” the answer seems to be “yes.”

A Chalice to Regret?

The anti-mining stance by the Catholic Church in Argentina was first prompted in 2005 by Fernando Maletti, then-bishop of Bariloche Diocese in Patagonia. His statement critiqued the use of cyanide in mining. The Calcatreu gold-silver development was rejected by the provincial government later that year, and the use of cyanide for mineral processing was banned by a provincial law. The ban was overturned in 2012, triggering massive protests. Nonetheless, not a single project has moved forward in Rio Negro since then.

Following Maletti’s anti-mining statements, then-bishop of Chubut Virginio Bressanelli stated in 2009: “We are uncomfortable that anyone can think, or believe, that this kind of business will be the salvation of the rural people.” Bressanelli was referring particularly to the massive Navidad silver-lead project in the meseta area of Chubut, located some 140 km (87 miles) south of Calcatreu. Open-pit mining has been banned in the province since 2003, after the town of Esquel rejected Canadian company Meridian Gold’s project in a local referendum.

Both Navidad and Calcatreu are owned by the Canadian multinational company Pan American Silver Corp., one of the world’s largest silver producers. Suggestively, the company hurried to supply the silver to make Pope Francis’s new chalice. Pan American Silver’s “donation” for the Papal chalice was announced by Argentine news agency Télam on March 23, 2013, which happens to also be an emblematic day for the anti-mining movement in Patagonia: the tenth anniversary of the Esquel referendum. The 1.3-kilogram (2.9 lb) bar of pure silver came from the company’s Manantial Espejo mine in Santa Cruz, which, unlike Rio Negro and Chubut, is said to be a mining-friendly jurisdiction.

However, Santa Cruz might not be as pro-mining as Pan American Silver would like. Like Maletti and Bresanelli, the Bishop of Rio Gallegos Diocese, Juan Carlos Romanín, has stated his concerns about the expansion of large-scale mining in Santa Cruz. Furthermore, according to the Latin American Episcopal Conference website, Bishops in Patagonia are in unanimous agreement that the need to interrogate large-scale mining practices due to their social and environmental impacts is becoming urgent.

Indigenous Communities, Handouts, and Gifts

The Navidad deposit contains 100 times the silver of the Calcatreu and Manantial Espejo mines combined. If brought into production, it would double the company’s actual global silver production. Pan American Silver acquired the then-operator of Navidad, Aquiline Resources, in 2009. The area is home to a number of small towns and indigenous communities that have not been consulted over the proposed mining.

Some residents say the mine should be permitted: a 7-year drought and ashes from Chile’s Pehuenche volcano, which erupted some years ago, have depleted their herds of cattle. But others vehemently disagree, claiming the mine will create a massive demand for water among other negative social and environmental impacts.

Pope Francis, when he was still archbishop of Buenos Aires in 2006, signed a document that described the large-scale mining projects in Patagonia as “affecting the survival of indigenous communities.” (A land for all (Una tierra para todos)) The document also pointed out that “mining projects severely affect the development and survival of indigenous communities. Companies seek their support presenting themselves as the solution to their needs and giving hand-outs and gifts.”

Pope Francis helped to establish the Equipo Nacional de Pastoral Aborigen (Pastoral Team for Ministry with Indigenous Peoples, ENDEPA), which supports indigenous peoples in their struggle to obtain legal land titles and forms part of opposition groups that fight mining projects.

In a statement released in 2010, indigenous communities potentially affected by the Navidad project demanded the right to choose their own development model: “We live of and for the land, of which we are a part.” Some of those communities have been struggling for legal recognition of their lands for decades.

Intimidation and Threats

One year ago, over two thousand demonstrators marched in Rawson, the capital of Chubut province in Patagonia, against the opening of the meseta region to large-scale mining. Two days prior to the demonstration, a similar, but much smaller group of protesters was violently attacked by thugs allegedly encouraged by the local affiliate of Pan American Silver, Minas Argentinas.

In February of this year, the Catholic news agency AICA reported that a Salesian priest in Gan Gan, Chubut, was intimidated by employees of Minas Argentinas for his opposition to large-scale mining.

The intimidation comes with government patronage. In a classic “revolving door” move, the former community relations manager of the Navidad project was appointed Secretary of Mining of the Rio Negro province in February 2012.

Spirituality and Mining

At the latest meeting of the Latin American Observatory of Mining Conflicts held in November in Lima, Peru, a group of Catholic Church and other religious members from the region formed a working group on mining and spirituality to address the social and environmental impacts of large-scale mining and to strengthen the Church’s local power to fight damaging projects. Participants included notables such as Guilherme Werlang, Bishop of the Diocese de Ipameri in Brazil, who has promoted a stronger role for the Church in the intervention in mining conflicts in Brazil, in particular those caused by mining giant Vale in the Carajás region.

Father Dário Bossi from the Articulaçao Internacional dos Atingidos pela Vale (International Network of People Affected by Vale) said that the meeting was “a first step for the development of a regional strategy to better understand the many issues of mining and coordinate the efforts regarding them.” A larger meeting is being planned to be held in Brazil this year.

These efforts join a long list of prominent Church leaders opposed to large-scale mining in Latin and Central America in the last decade, such as Fernando Sáenz Lacalle in El Salvador, Gaspar Quintana in Copiapó in Chile, or Álvaro Ramazzini in San Marcos, Guatemala.

My Own Journey From Faith to Activism

Before becoming an anti-mining activist, I travelled around the meseta region of Chubut province in Patagonia as part of the missionary group of a church in Puerto Madryn, my hometown. The Navidad project didn’t exist then. When foreign mining companies began to arrive in the Chubut province in search of precious metals in early 2000, it felt reasonable to extend my faith to activism. Later, I joined the Endepa group in my Diocese to help amplify the voices of indigenous communities concerned about their future as the underground water sources and lands on which they depend could be destroyed forever. It is from my own experiences at the crossroads of faith and activism that I write today.

Luis Manuel Claps studied Communications at the Buenos Aires University. He has followed mining in Latin America since 2004 as editor of the Mines and Communities Website. He is based in Lima, Perú.