By Javier Farje, LAB

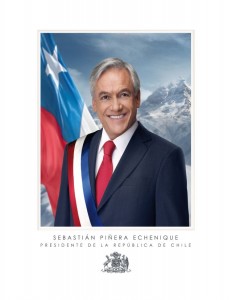

.jpg) Sebastián Piñera has a problem. After two decades of centre-left government, this conservative millionaire needs to show that he is his own man, with his own policies and his own identity. Not an easy task if we consider the fact that, since Chile returned to the democratic fold in 1989, Chileans have grown accustomed to be governed by a political coalition that has transformed the country into a stable entity. The Concertación’s handling of the economy has seen Chile’s trade and investments grow to unprecedented levels.

Sebastián Piñera has a problem. After two decades of centre-left government, this conservative millionaire needs to show that he is his own man, with his own policies and his own identity. Not an easy task if we consider the fact that, since Chile returned to the democratic fold in 1989, Chileans have grown accustomed to be governed by a political coalition that has transformed the country into a stable entity. The Concertación’s handling of the economy has seen Chile’s trade and investments grow to unprecedented levels.

On the one hand, Piñera has let it be known that he has no intention of dismantling the reforms carried out by his predecessors. But, on the other hand, he needs to please members of his coalition, many of whom come from the Pinochet era. It will clearly be a juggling act.

In some ways, his relations with Concertación will be easier to handle than those with the pinochetistas. Indeed, it would be difficult for this multimillionaire businessman to change the economic policies of the Concertación. After all, Chile has achieved a real average rate of economic growth of 3% a year, despite a downturn in 2009 due to the world recession; and it has promoted exports in sectors not associated with copper, Chile’s main primary commodity export.

Piñera is a direct beneficiary of the economic openness shown by the Concertación governments, having amassed a vast fortune. Only his share of LAN, Chile’s semi-privatised national carrier, is calculated at US$1.5bn. He also owns Colo-Colo, one of the country’s most popular football clubs, along with some media outlets.

It is not only rich businessmen who have done well. Even though Concertación has been criticised by the left for doing far too little to tackle social inequalities, most Chileans have benefited. Chile has improved its position in the annual human development index, drawn up by the UN Development Programme.

Piñera is also planning to continue with other Concertación’s policies, not just those in the economic sector. He will carry on in more or less the same way with the Concertación’s external policies, including the current sea border dispute with Peru. After he met outgoing President Michelle Bachelet, he also said that he’d continue the policy of distribution of the so-called “day after” contraceptive pill, even though social conservatives strongly disapprove of it.

So continuismo will be marked. Indeed, in a speech after he was elected, Piñera did not rule out the possibility of inviting members of the outgoing government coalition to join his cabinet.

Pinochet’s shadow

However, many followers of former (and dead) dictator Augusto Pinochet climbed on the Piñera bandwagon in order to exercise some kind of influence on a political system that largely considers the old murderous general a page in history that most Chileans have turned over with relish and relief. In the run-up to the elections Piñera welcomed their support and now they want their pound of flesh.

At the start of the transition to democracy, the pinochetistas formed political parties that had some weight in a country that was emerging from the dark years of the dictatorship wounded and hesitant. Furthermore, the dictator infiltrated the newly-gained democracy with “for life” senators; these became a thorn in Concertación’s side, but the new democratic governments reluctantly accepted them as the price to pay for a peaceful transition.

But, little by little – and particularly after the government dared to abolish the “for life” senators – the pinochetistas’s influence started to diminish.  And many old supporters of the retired tyrant abandoned ship when their boss and his family were prosecuted for corruption, a cloud that still hangs over his widow and his children. “Kill and torture opponents, if you will, but don’t steal” seemed the motto of the Pinochet clique.

And many old supporters of the retired tyrant abandoned ship when their boss and his family were prosecuted for corruption, a cloud that still hangs over his widow and his children. “Kill and torture opponents, if you will, but don’t steal” seemed the motto of the Pinochet clique.

Many believed that Piñera’s movement, the Coalition for Change, was the best place to maintain some kind of influence. The biggest party in Piñera’s Coalition for Change is the Independent Democratic Union (UDI in Spanish), the most right-wing component of a somehow eclectic alliance. UDI organises and defends the “achievements” of the Pinochet era. And the newly elected president needs their support in parliament to govern. If we consider the fact the Coalition for Change has just one MP fewer than the Concertación, and that Piñera will need the support of smaller parties to have his bills sanctioned, it is easy to see why the new president will be unable to alienate his far-right allies.

But Piñera is not a pinochetista. He was a young student in Harvard when Pinochet’s forces bombarded La Moneda and deposed the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. And when he came back to Chile, he voted “No” in the 1989 referendum organised by Pinochet in the vain attempt to have Chileans confirm him in office for a further period. Pinochet lost the referendum and the start of the transition for democracy brought to power a centre-left alliance ready to embrace market economics.

The young professional joined the Christian Democratic Party and later abandoned politics to devote himself to business. He joined Citicorp, a branch of Citibank, and in 1987 he formed a company that became the biggest provider of credit cards in South America, despite the initial misgivings of fellow businesspeople who believed that the continent was not mature enough to handle plastic money.

In 1992, his chances of becoming a presidential candidate were ruined by a recording, broadcast on a rival TV station, where he appeared to be trying to manipulate a political debate with a fellow conservative pre-candidate. The recording of that conversation was made secretly by far-right elements of the army, who hated the idea of having a conservative president with liberal ideas who could jeopardise Pinochet’s “legacy”.

Perhaps, unwittingly, this ruse to ruin Piñera’s electoral chances may have benefited him in the long term. Since then, he has always used this chapter in his political career, strangely called “Piñeragate”, to insist that he cannot be considered a Pinochet sympathiser or his ideological heir.

Middle-of-the road conservative

Many moderate right-wingers in Latin America have great hopes in Piñera.

Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, and old friend of the new president, is ecstatic. In an article published in the Spanish daily “El País”, Vargas Llosa, who used his piece to justify the military coup against Allende, believes that Piñera can reverse the left-wing trend that has dominated much of the continent.

“In the Latin American context”, writes Vargas Llosa, “the victory of Sebastian Piñera is a serious setback for lieutenant-colonel Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, and the bunch of countries – Cuba, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Ecuador – that, under his leadership, want to impose a populist and authoritarian model on Latin America”.

Like some of his fellow conservatives, Vargas Llosa believes that Piñera will encourage countries like Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Peru, Uruguay and Brazil “to defend democratic culture and resist the authoritarian offensive that, from Caracas, is trying to take the continent back to collectivism (…) and populist demagogy”.

The problem is that, despite his credentials as a moderate conservative and a man ready to work with his political foes, he still faces some challenges that may make the proverbial honeymoon short.

On one level, he needs to shake off the idea that the pinochetistas will have some kind of real influence in his government. During the election campaign, his opponents questioned his qualification as a democrat because of his friendship with the UDI. Asked if he would invite followers of the dead despot into his cabinet, he appeared elusive and annoyed. Even so, it didn’t wreak his chances: people wanted change and he represented that change.

Challenges

As a businessman, there are worries that his vast economic interests will influence his presidency. Some have gone to the extreme of comparing him with Italy’s Silvio Berlusconni, who, like Piñera, owns media organisations.

As a businessman, there are worries that his vast economic interests will influence his presidency. Some have gone to the extreme of comparing him with Italy’s Silvio Berlusconni, who, like Piñera, owns media organisations.

Piñera has started to get rid of some of his interests in the companies he either owns or where he has shares, but some people, like the outgoing Finance Minister Andrés Velasco, believe that he should have done that before the election and not have waited until he was elected to do so.

As soon as his victory was announced, shares in some of his companies soared on the stock market and that has not gone down well among those who believe that Piñera has too many conflicts of interest to govern with transparency.

The new president will also face another test that may define the separation between his personal interest and that of the country’s government.

A new law, to encourage the expansion of terrestrial television into digital television, will be in place soon. And Sebastián Piñera, who own Chilevisión, a TV channel that plans to take advantage of the new legislation, will have to use this situation to show that he won’t interfere or use his presidency to further his own interests.

However, to suggest at the moment that the new president will mix business with politics would be not only unfair but also premature.

So far, his rhetoric and approach to the Concertación government have been conciliatory. He is making serious attempts to portray himself as a liberal conservative, a Catholic who is prepared to listen to those who do not agree with him.

And he needs to tackle the profound inequalities that still affect Chilean society. Despite the fact that Chile has improved its position in the index of human development, 18% of Piñera‘s fellow citizens live below the poverty line. And the recovery of the economy has not improved the chances of thousands of Chileans of getting jobs.

In one way, Piñera’s election is undoubtedly positive: it shows that Chilean democracy feels itself strong enough to elect a candidate who does not represent the political forces that led the country back from dictatorship to a democratic political system. And the reconstruction of large parts of Chile after the devastating earthquake will be his first big challenge.

The Concertación represented those parties that helped to erase the terrible years of oppression from the hearts and minds of Chilean society. And Sebastian Piñera is supposed to represent the necessary political change that confirms that the transition is complete. Not an easy task for a business manager who wants to be everybody’s president.