This is a condensed version of a longer article written in July 2020. It was edited for LAB by Emily Gregg.

Indigenous territories in Latin America are critical areas where the COVID-19 has had a major impact on vulnerable communities. The Atacama people in Antofagasta, Chile, are one example of how these communities have taken their own action to protect themselves from the disease. However, voluntary lockdowns and barriers at town entrances have created conflict with authorities and encounters with the police.

The Atacama Desert stretches from Antofagasta to Copiapó. It is home to the indigenous Atacama peoples, who are known for their ability to harvest in harsh conditions. In recent years, their ancestral lands have become popular with tourists, with San Pedro de Atacama becoming one of the country’s tourism hotspots.

Mining interests prevail

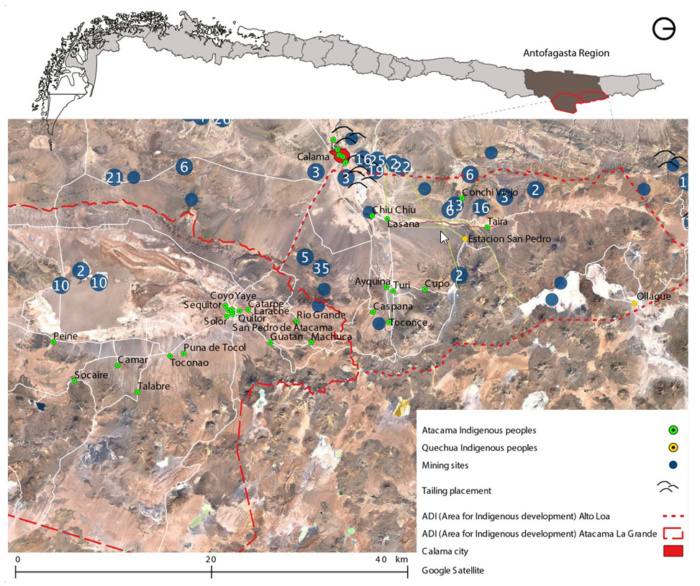

These lands are now also dominated by mining; the map above shows that there are now more mining projects than indigenous pueblos or villages in the region. The city of Antofagasta itself operates as the centre of the mining industry in the area, and workers commute from across Chile and neighbouring countries to work in the region’s mines. The local people have a complicated relationship with the mining sector, which at once provides jobs but also threatens their local environment, and in times of coronavirus, their health.

Since Coronavirus arrived in Chile in March, the country’s neoliberal government has taken an erratic approach to lockdowns, guided more by economic motives than concern for people’s health. Given the importance of mining to the Chilean economy (the sector provides 8.9 per cent of the country’s GDP) the government has been reluctant to lockdown the Antofagasta region. This has been at the expense of indigenous groups, whose vulnerability has been exacerbated by extractive companies. Although they live in isolated areas, mining activities have carried the disease far from cities, and Antofagasta has one of highest rates of infection outside of Chile’s capital.

Peine (on the right-hand side of the map) was the first to close its entrance to mining companies and tourists, on 20 April. Some locals declared that many tourists from Japan and Brazil were still making accommodation requests due to its proximity to the tourist hotspot, San Pedro de Atacama. The ‘floating population’ of mine workers also continued to the move through the area. Locals placed barriers on access roads often used by a mining company. The community refused the police request to remove the blockade and were threatened with arrest. However, within a few days the mining company accepted that measure and left the area.

Road blocks and sanitising

As social pressure mounted, a hygiene protocol was brought in on 13 May. Hospital professionals from Calama delivered PPE to Alto Loa and educated locals about hand sanitation. However, by 22 May there were Covid outbreaks in Toconce, Ayquina and Chiu Chiu. These areas do not normally see mining traffic, are not popular destinations for visitors. Rather, they are traditional Atacama communities. Their populations are mostly indigenous people (except for Chiu Chiu) and often have a large elderly population. By that time, only the village of Ollague in the Alto Loa area had no registed cases.

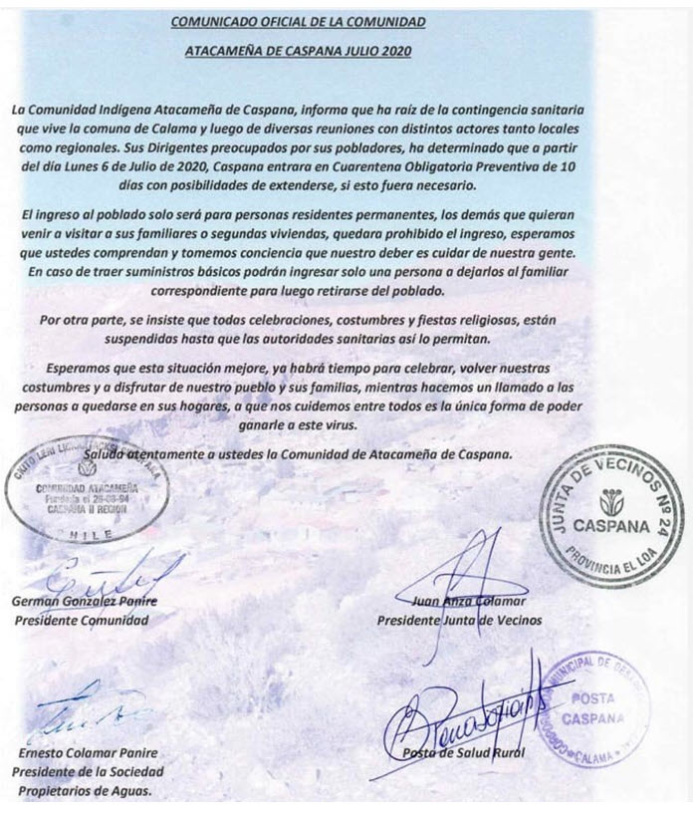

Calama entered lockdown on 9 June, but the measure only applied to the urban area – not to the two indigenous areas where mining operations are located. Despite Calama’s lockdown, people from the city continued to visit the villages to see their families. Aware of this issue, the Caspana community, decided to ban non-residents from visiting their families, even when there was no lockdown in place in the region. The community later closed its entrance with a road block. To date there is no COVID-19 case in Caspana. The road block remains in place although it is not under strict control.

Dangerous visitors

After the first cases were confirmed in Ayquina, the community closed its own entrance road. The barrier that blocked the road held signs that read ‘Ayquina is in quarantine, do not come to the village’. In Ayquina, however, people from Calama were not only visiting family members, but staying at their second homes. One member of the Ayquina community described to a local newspaper a significant absence of policies that address their particular needs as a cultural group. The area was instead considered ‘the backyard of Calama’. For those reasons, he said, they were enforcing their own measures.

In the area of Atacama La Grande and near San Pedro de Atacama, the Consejo de Pueblos Atacameños (Atacaman People’s Council) made a formal complaint to the national human rights observatory, highlighting the way in which the pandemic had increased their vulnerability. At the time, there were 100 confirmed cases of coronavirus amongst the indigenous populations and mining companies were still operating in the sector.

Cordon sanitaire

On 3 July a panel made up of community members issued a statement on social media. The statement described the authorities’ lack of humanity and dignity when it claimed that the situation in the region was under control. They noted that cases were counted on the basis of the 2017 census, rather than the current smaller population, meaning that the rate of infection was underestimated. They emphasized the lack of registration of cases, absence of effective tracing, and the deaths of community members. The panel demanded a quarantine hostel for the locality to avoid infection and to protect the elderly, the chronically ill and children. Black flags were raised outside a local church to symbolise the authorities’ refusal to listen and their abandonment of indigenous communities.

In the same speech, however, the community panel spokesperson praised the actions of other towns such as Peine and Rio Grande, where people organised to create ollas comunes (soup kitchens), to block village entrances, enforce voluntary quarantines, support migrants in returning to their countries, and consider people’s mental health.

Quillagua, in the north of the region, has been the worst-affected of the local indigenous communities. Thirty of its 150 habitants had tested positive by 17 July and 85 people had to self-isolate. Mining companies working in the area are accused of bringing the virus to the territory. The situation is made more severe by the lack of drinking water in Quillagua and a river contaminated by mining pollutants.

Felisa Albornos, aged 83, died in the first week of July from Covid. She had been in charge of the local museum. Her death shocked the community and highlighted the threat the disease represents to the elderly. The Quillagua community enforced a voluntary quarantine and implemented a road block to control who enters the village. However, companies associated with mining in the Quillagua called the police, who removed the barrier. SQM, the main company operating in the area donated an ambulance, food boxes, and sanitary kits, as well as a disinfectant service for local houses. However, thirty people have fallen ill since the removal of the barrier.

The economic impact of the pandemic has given rise to other conflicts. Since the countrywide protests against the government and neoliberal system started in October 2019, the Chilean economy has suffered. Many companies laid their workers off in the uncertain conditions.

As the pandemic caused further financial contraction, the El Abra mining company, which works on a project near Conchi, dismissed 275 workers, including 25 local indigenous people. Locals again blocked vehicle access to site. This time, however, it was in response to the loss of work in the mines, demonstrating indigenous peoples’ complex relationship with the mining sector.

In an interview with the author, Claudio, a member of the Chunchuri indigenous urban community and who works in Chuquicamata, described the labour situation as hostile. He is the only member of his family of five brothers currently employed. He mentioned that he thought it was unlikely that CODELCO (the state mining company in Chuquicamata) would stop its copper production. CODELCO has been under further pressure from miner unions to scale down its projects to protect workers from the virus. As of 9 July, over a third of the 2,842 mine workers infected with Coronavirus were CODELCO workers.

Lack of clean water

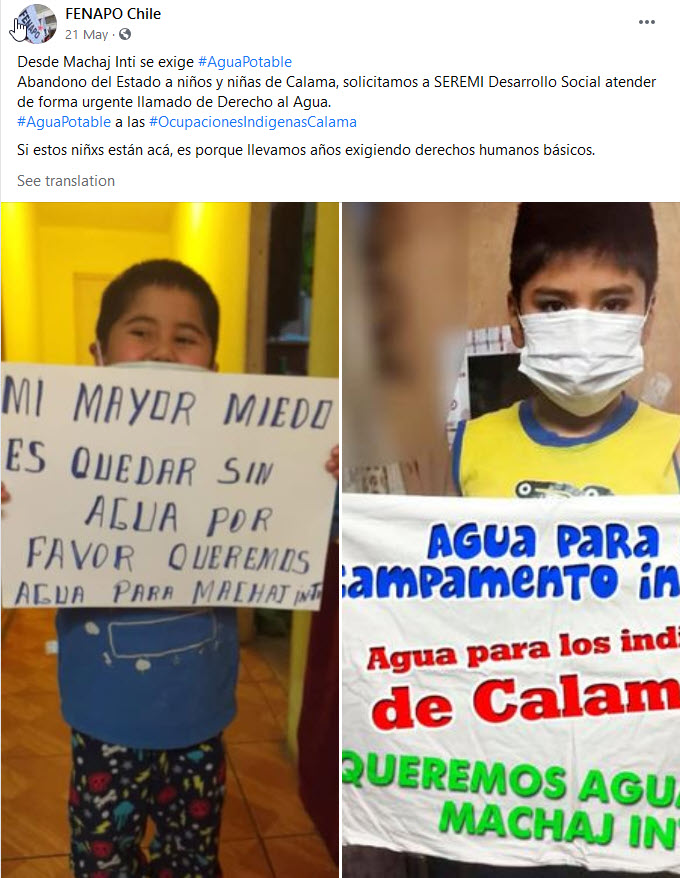

Indigenous people living in Calama itself have also suffered during the pandemic. At the beginning of July, the National Federation of Settlers and Villagers of Chile (FENAPO) publicised the dire living conditions of the indigenous association, Machaj Inti, in the city. Since the Machaj Inti is an association, in Chile they do not have the legal right to reclaim an ancestral territory within the city. The association’s members have migrated from different indigenous communities and regrouped in the city, aiming to maintain or reconstruct their identities and social structures.

Members of the Machaj Inti – like most indigenous people living in cities – are unable to apply for social housing. Instead, then, they live on occupied land in shacks or flimsy houses. The dwellings are not connected to the drinking water system, and the occupants depend on a tanker truck. The only truck available in the city had technical problems and the entire association was left with no water.

When the pandemic reached Calama, the situation escalated as no one could wash their hands to prevent the spread of the disease. By 20 July, the mayor, whose jurisdiction includes Alto Loa, began a mass testing campaign in all the indigenous villages, looking for asymptomatic people in the areas which had seen cases earlier in the month. This action followed a serious political crisis in Calama Municipality after 5,057 cases were confirmed positive with deaths 2.5 per cent higher than the national rate.

Fools’ gold

Claudio from Chunchuri explains that by contrast the mayor of San Pedro de Atacama mayor carried out no such campaign, despite the large donations that mining regularly make to the municipality. The Consejo de pueblos Atacameño wants to know how the donated money will be spent. Arguing that this is no time for saving, they want the money to be invested in a new health centre and quarantined housing.

The reactions of the indigenous people in the Antofagasta region show their determination to manage their own actions in relation to the health and the protection of their communities. It could also serve as a lesson for governments about the necessity of looking after the elderly who, as Claudio from Chunchuri says, are not forgotten but guarded as ‘living treasures’.

Main image: Ayquina barrier and signs. Photo: Rene Paniri / Toconaoradio official