‘While water no longer even runs from the taps of our houses and day by day our territory is devastated, Anglo American’s open-pit mine El Soldado continues its operations without running out of water,’

Ximana Gallardo, El Melón

Ximena Gallardo is a resident of El Melón, a town of 9,000 habitants in the Valparaíso region, where about 40 per cent of families have no access to running water at home. As a result, Greenpeace Chile recently launched a campaign calling on Anglo American to #SueltaElAgua [#FreeTheWater].

Most of Chile has been suffering from severe drought over the last decade, partly as a result of climate change. But while the government blames the drought for the water shortages in the village of El Melón, Anglo American’s nearby El Soldado project has remained largely unaffected. The largest copper project in central Chile, El Soldado has 16 deep water wells and 19 permits for exploitation of 453 litres of water a second. In contrast, El Melón has had access to just eight litres a second since 2019, though at least 30 litres per second are needed to supply the whole community.

‘What we’re sure of is that the mine will always need more water to ensure its operation and expansion,’ says Gallardo. ‘With things the way they are, the only future we have as a community is to have less and less water for human consumption and for the environment.’

On 24 October 2019 residents sent a petition to Anglo American, requesting they share some of their abundant water supplies. The company ignored them. In response, members of the El Melón Organized Civil Society (SCOEM) seized one of Anglo American’s wells on 7 November. While the company then agreed to divert 15 l/s of their water to the community, it was still not enough to ensure water security for the community, including the local nursery and health centre. The occupation continued for three months, until it was removed by the security forces.

Then, on 17 April 2020, the community of El Melón, together with the local environmental group Poyewn, filed an appeal with the Valparaíso Regional Court of Appeals, claiming that overexploitation of water by Anglo American had caused shortages for local people. However, the court rejected the appeal, arguing that lack of water in El Melón is due to low precipitation levels in the region and the poor condition of infrastructure, rather than Anglo American. Moreover, as Chilean law gives water the same status as any other tradeable commodity, the company is under no obligation to share its water with third parties living on the land where its rights were acquired.

In response to the Greenpeace campaign, Anglo American created the video #QuéQuieresSaber [#WhatDoYouWantToKnow] in which they responded to questions asked by residents of El Melón. Anglo American rejects responsibility for water scarcity in the region and claims to have implemented 60 projects to resolve the problem, including connecting two wells to the municipal supply, delivering more than 60,000 litres of water via cistern trucks and modernising infrastructure. They also claim that most of the water used at El Soldado is recycled from its operations.

Anglo American’s ‘sustainability’ strategy – what it calls ‘FutureSmart Mining’ – covers sustainable water management, supposedly involving regular assessment of water availability and quality. And yet, in the case of El Melón, the community has been suffering from shortages for years. This widespread abuse of the concept of sustainability by Anglo American and other companies in the extractive industries has reduced it to little more than a meaningless buzzword.

‘This is not drought, it’s looting’

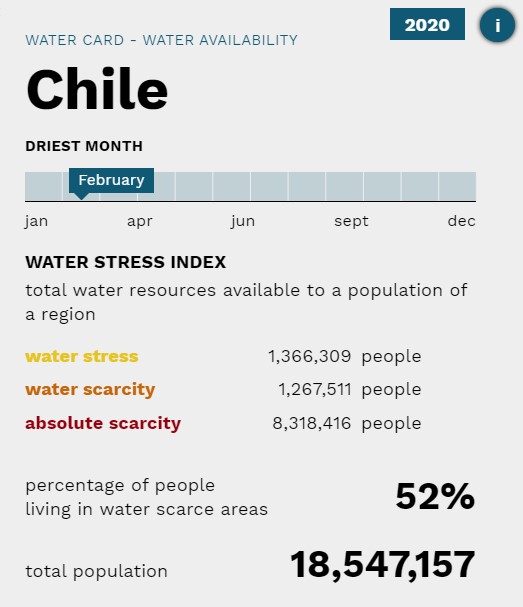

The Water Stress Index from 2020 indicates that 52 per cent of Chile’s population live in areas suffering from water scarcity. While climate change is a major factor, it is not the only one.

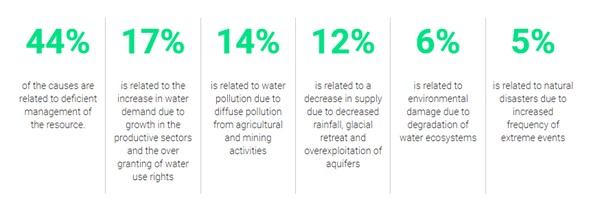

A study by Fundación Chile which looked at six different water basins – Copiapó, Aconcagua, Maipo, Maule, Lebu, and Baker – showed that 44 per cent of water shortages are caused by poor water governance. Other reasons include overexploitation by productive sectors, excessive granting of water rights, water pollution by mining and agricultural activities and the degradation of water ecosystems.

While 78 per cent of the country is affected by drought, 98 per cent of the national water supply is controlled by industry. The pressure this puts on water reserves affects both water users and ecosystems, and the most affected areas – from the north, down to the Santiago Metropolitan Region – are also those where the presence of mining companies is heaviest. The government’s solution is simply to provide these areas with a water cistern service; 61 out of 346 municipalities now rely on this form of supply. According to the National Emergency Office (ONEMI), more then 8,000 people were supplied by water tank cisterns in 2019 in the Valparaíso Region.

For Lucio Cuenca, director of the Latin American Observatory of Environmental Conflicts (OLCA), aside from the poor governance of water resources, the main cause of water scarcity in Chile is its privatisation and commodification.

Chile’s water code is a relic of the dictatorship which reinforced the status of water as a private commodity, as laid out in Chile’s Constitution (art. 19 nr. 24). Investors and companies bid for rights which, once acquired, are held in perpetuity and may be bought and sold like any other commodity. This means not only that the government has no control over water consumption, it is not even aware who holds the rights to certain sources of water.

‘Privatization and its consequences, commercialization and its consequences – this is at the heart of the problem we are experiencing today,’ says Cuenca. ‘This has allowed the concentration of water by the most powerful economic sectors, leaving the general population, indigenous communities, the conservation of ecosystems and biodiversity, completely unprotected.’

The Failure of the ‘Chilean Model’

Water scarcity in Chile is therefore a structural issue requiring changes in legislation which have been rendered even more urgent by the Covid-19 pandemic. The social unrest from 2019 provides yet more proof that the Chilean model of development – a model built by Augusto Pinochet and left largely intact by the democratic governments which followed – has failed. It has permitted the exploitation of ecosystems beyond their capacity, facilitating the access to Chilean natural resources by the extractive industries, both national and foreign.

‘The fight for water, the fight for climate justice, is simply a fight for social justice,’ says Sebastián Muñoz, Senior International Programmes Officer for Latin America at War on Want. ‘Because water is used without limits by mining companies to expand their economic growth and thus provide the incalculable demand of the northern countries. The same water supplies the people who depend on it for their agriculture, for their daily lives, for drinking, as a vital source.’

Propaganda surrounding Chile’s economic model created a distorted image of success, both at home and abroad. The message was clear for the other countries in the region: if they would only follow Chile’s example and radically open up their economies to foreign investment, they would enjoy the same prosperity. But now, like El Melón, people all over the country face an uncertain future.

‘As a community, our identity is disrupted, our culture is disrupted, our history is contaminated,’ says Andrés Marín, a spokesman for El Melón. ‘We are surrounded by this dialectic, from the politics, from this reasoning of the country, which tells us that we are miners – so that we’d accept the violence, so that we’d accept that we will die of thirst!’