‘No son $30‘

On Friday 18 October, Chilean president Sebastian Piñera announced a state of emergency in the country’s capital Santiago. As protests spread throughout the country over the following days, the state of emergency and its accompanying curfews were also extended.

Chile has not experienced a state of emergency since the one declared in the wake of 2011’s devastating earthquake, and has not endured a state of emergency accompanied by a curfew since 1987, under Augusto Pinochet’s repressive military regime.

The recent protests started in Santiago after an increase in peak subway and bus fares was announced, raising the cost of a trip to 830 pesos (US$1.17). In reaction to the increase, protestors – mainly secondary school and university students – jumped the subway turnstiles in large groups.

The protests, termed ‘evasiones’, were criticised by the Government because the increase did not affect the student fare. The PPD senator and member of the Commission for Public Security, Felipe Harboe, criticised the protest as an ‘unacceptable millennial expression’.

However, the students successfully shut down the subway network, bringing Santiago to a standstill and attracting global media attention.

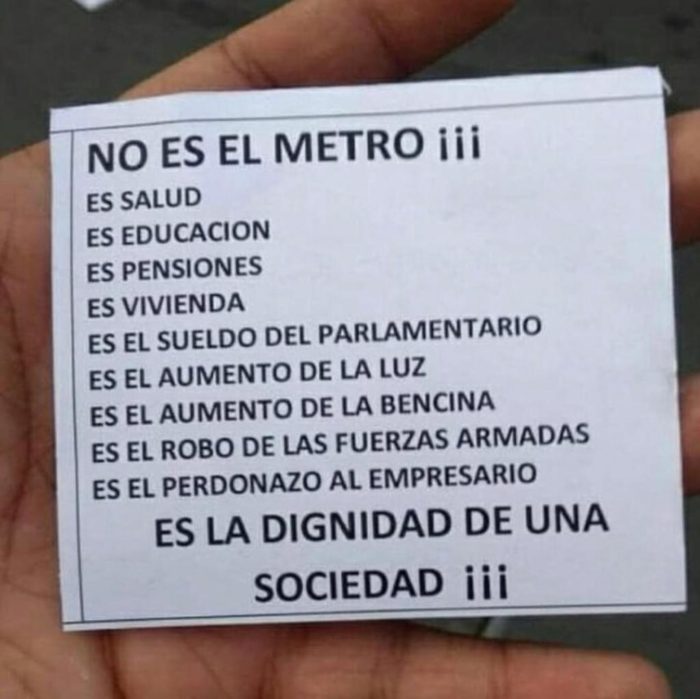

The increase of the subway fare was suspended in wake of the protest. But the increase is only the tip of an iceberg of deep-rooted and widespread discontent. It represented the progressively unmanageable cost of living in Chile for the majority of the population, the overbearing inequality, and an out-of-touch government.

So, when carabiñeros (the Chilean police force) released teargas on the platforms and detained those who carried out the evasiones on Thursday 17, the protests quickly became a manifestation of discontent toward the Piñera administration and gained the support of vast and varied sectors of society. The brutality of the carabiñeros towards the protestors, many of whom were minors, showcased a system of repression against which hundreds of thousands of Chileans turned out to protest over the weekend. They demanded – and are still demanding – their right to live in dignity, their right to a free and fair education, and the end of inequality.

‘Educación sin lucro’

Students leading the protests are seizing the opportunity to make their own specific demands heard. They are still profoundly unsatisfied with the frustrating and inadequate reforms which followed the 2011 movement, when hundreds of thousands of students took to the streets in opposition to the for-profit education system. Despite some successes, which included the decentralisation of the administration of schools and the Inclusive Education Act that increased the number of scholarships available, the reforms have failed to change the fundamental commercial and competitive characteristics of an education system that prioritises private profit over material resources for schools, a dignified pay for teachers, and free universal education for all.

Today, many schools and universities up and down the country remain shut for safety reasons and students continue to lead the protests.

‘Chile está en la calle pidiendo dignidad’

However, education was not the only issue that brought Chileans to the streets. Protesters criticise the widespread privatisation of public services, including water and electricity, characterised by unmanageable price hikes. Electricity prices have increased twice this year already, each time by 10%.

The pharmaceutical industry has also come under attack for their part in charging the public extortionate rates for vital services in order to increase their own profits. An investigation carried out last month by the television channel Canal 13 revealed pharmaceutical companies to be extracting exorbitant margins of profit, making the industry the second most lucrative in the country after arms, while health insurance only covers 5 percent of medications.

The pensions system, which epitomises Chile’s neoliberal economy, is a further source of discontent. In Chile, private pensions have completely replaced the public system. The present AFP (pension fund) model was introduced in obedience to the neoliberal, free market presumption that competition between private companies would encourage better pensions and services. But of the 20 pension companies that existed when the system came into force, only six remain. These six all provide more or less the same product, one which does not return the value of the contributions made by workers, and which pays out so little that pensioners are forced to live below the poverty line or continue to work, meanwhile enriching the companies’ owners.

According to the grassroots organisation leading the ongoing campaign against the system, NO+AFP, these six companies constitute large monopolies within Chile’s economy, owning major supermarket chains, banks and petrol companies, amongst other assets. They perpetuate a cartel by mutually supporting each other and fixing ever higher prices, thus annulling any competition. Their political lobbying and systematic corruption ensure that they are neither scrutinised or questioned.

Protestors marched with signs that read, ‘I’m not afraid to die… I’m afraid to retire’ showing the dire situation of pensioners in the country. Those who took to violent protest targeted the supermarkets and banks that belong to these families as well as branches of the AFP firms.

The frustration of the protestors that their government is out of touch is clear. A 2014 study showed Chile to have the highest parliamentary wage compared to GDP per capita across the globe (Schaeffer and Valenzuela). According to a recent report from the Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, half of Chile’s workers earn CLP $400,000 (around £425) per month or less. But Chilean senators and deputies earn a gross monthly salary of CLP $9,349,851 (almost £10,000) plus expense budgets totalling a further $20 million for senators and $11 million for deputies.

#PiñeraDictator

On Monday (21 October), Piñera made a public announcement that claimed that Chile is in ‘a state of war’ against ‘the enemy’. It is a statement sinisterly evocative both for Chileans who lived through the 17-year military dictatorship , when the rhetoric of the ‘enemy within’ was used to justify brutal repression and human rights abuses, and for the younger generations who have lived in its shadow.

The deployment of such rhetoric is a clear attempt to divide the country, as it did over 30 years ago, this time blaming Chile’s problems not on the Left, but on ‘delincuentes’ – low-level criminals and anti-social trouble makers. One observer described the tactic as ‘penal populism’, that serves as a further development of the Piñera administration’s increasingly harsh measures against anti-social behaviour.

While some protestors have taken a violent approach, photos and videos have circulated on social media of carabiñeros starting minor fires to increase the perception that the protests are nothing but trouble caused by these ‘delincuentes’.

The media too has played a role in this perception. Television broadcasts especially have focused more on the minority of violent and destructive protests than the peaceful cacerolazos (pot-banging protests that originated during the famine of the dictatorship era). Even less is shown of the police and military violence against the protestors that has included widespread use of tear gas and water cannon, and all too frequently included beatings and using live ammunition against mainly peaceful marchers.

As of Wednesday morning, the figure of those arrested for participation in the protests totalled 1,692. The Chilean National Institute of Human Rights (INDH) has also reported that some of those arrested have been submitted to excessive force, mistreatment, beatings to the face and thighs, torture, and sexual harassment, while women have been forced to strip and minors have experienced harassment. The INDH also confirmed that 226 people have been injured, of whom 123 were injured by firearms. The public body is taking legal action against the military and carabiñeros for the deaths of people, which they denounce as homicide and will launch 26 further lawsuits in favour of 129 victims.

Yet just a few weeks ago, Piñera condemned the Venezuelan regime for human rights abuses, corruption, and lack of respect for liberty.

Un Pueblo Unido, Chile Despierto

But the people are united. Students and others have taken to the streets to clean up the rubbish and mess. Small groups have begun to defend small businesses from damage and to continue peaceful demonstrations. They maintain that the enemy is not each other, but the system. Social media has not only allowed people to organise, but to share images and videos of the brutality that they face and is seen as a form of protection, a means to hold the state and its security services to account.

Over the next few days, politicians will continue to meet to discuss how to move forward and how to create a new ‘social pact’. The protests also promise to continue as the CUT, one of Chile’s major trade union federations, holds a general strike. On Tuesday night, Piñera promised to increase pensions, improve healthcare, and to tax the highest earners. But the problems are too deep and tensions too high to be settled with a compromise as they have in the past. Any solution would require the ruling classes to renounce their privileges: their wages, their ties to the economic monopolies, their lack of accountability to the law.

The perception of Chile as the ‘Switzerland’ of Latin America, for its stability and prosperity, has been shattered. #ChileDesperto has mobilised a nation, depoliticised through a lack of faith in their representatives, and caught the attention of the world. For now, it seems Chile will not rest until it gains the peace and dignity for which it has waited over 30 years.

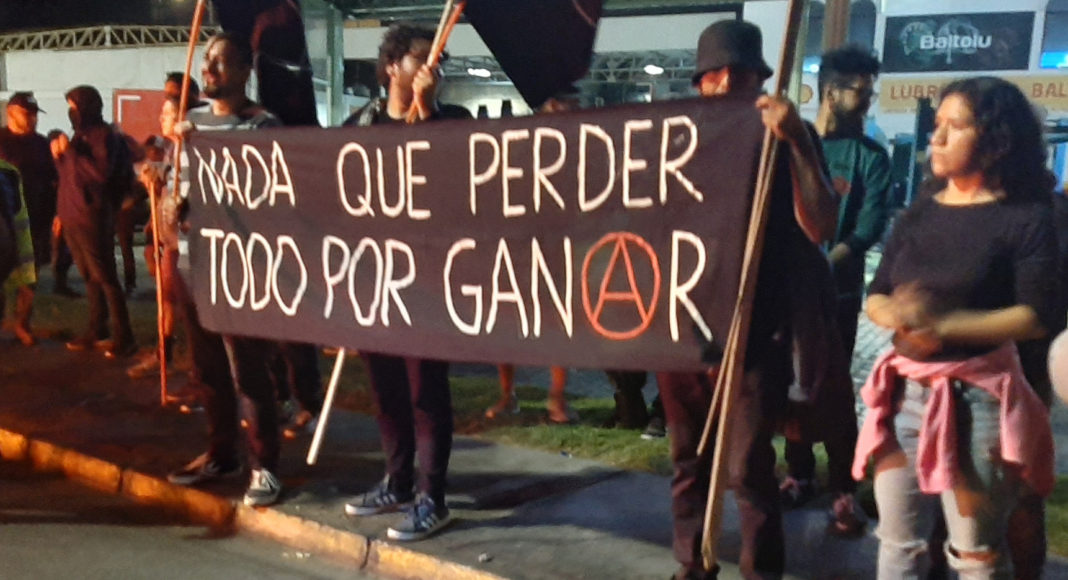

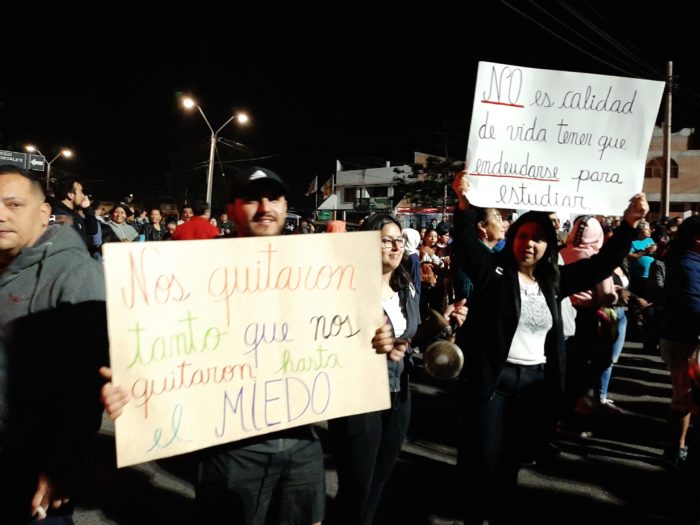

Gallery of photographs of the protests in Arica, taken by Emily Gregg.

Arica

I have written this article from the small city of Arica, the northern-most city in Chile. It is sleepy city where the degrees of separation seem to be closer to two than six, and which is trapped between a sea full of surfers and the Andean mountains. It has a population of just under 230,000 according to the latest census figures, but 21.8% of that population live in ‘multidimensional poverty’, which not only measures income but also level of education and access to healthcare and other services including housing and transport. The figure is 1.1 percentage points above the national level.

Before the protests began, the general feeling of frustration with the system was felt. The students I work with complain of the lack of resources in their schools and universities and many see few opportunities to work once they complete their studies. Friends who have received healthcare treatment have noted the lack of appropriate medicines and equipment in clinics and hospitals. All over the city there were signs left from previous protests against AFP, against machismo, capitalism, and mining, and against hostile migrant and environmental policies.

The recent protests have brought these issues to the fore again. Probably due to the size of the population, the demonstrations here have been much smaller and calmer than in the central region; a state of emergency and curfew was not declared here until Tuesday, five days after Santiago.

Nonetheless, since Arica is a key training ground for the military and carabiñeros, their presence has certainly been felt. Peaceful protestors have been attacked with teargas and water cannons. Some of the many who have a friend or a relative in the security forces have been afraid to go out on the advice of their contacts.

But while they may be few and remote, and despite the military presence, Ariqueños have played their role in catching the attention of the government. There have been daily protests throughout the city since last Friday that have varied from marches and cacerolazos to DJ sets and dancing. Those I have spoken to are determined to continue until they are heard and satisfied. While life may be a little more difficult during the protests as supermarkets and banks limit entry and opening hours, and healthcare and education centres are on strike, it is a sacrifice most are willing to make for justice and a long-term improvement to their livelihoods.

Emily Gregg is a LAB correspondent and author, now based in Arica, Chile. She wrote The Student Revolution chapter in LAB’s book Voices of Latin America (2019).