This article was written by Francisco Gutiérrez Sanín, Professor at the Nacional University in Bogotá Colombia, and a partner on the Drugs & (dis)order Research Project at SOAS, University of London

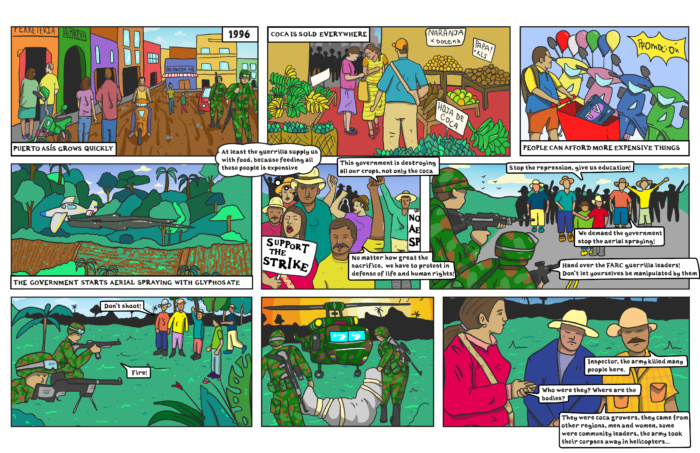

Four years after a Peace Agreement that formally ended more than 60 years of internal conflict, there’s a new wave of violence in Colombia. More than 46 massacres so far this year, and intimidation and assassination of social leaders is getting worse. President Ivan Duque blames it all on illicit coca crops. The best way to protect the peace process, he says, is forced eradication of coca.

This does not match existing evidence in any sensible way. The resurgence of violence in Colombia is not a result of illicit coca cultivation, but a result of the Duque government’s many failures, including the failure to implement the illicit crop substitution programme that was set up under the 2016 peace agreement.

Designed to give smallholder farmers subsidies to swap illegal crops for alternatives, the crop substitution programme (known as PNIS) was an important part of the peace deal. It was also intended to combat years of social and political exclusion of coca farmers, and was supposed to be linked to regional development and infrastructure plans.

Nearly 100,000 coca farming families signed up to the programme. But the subsequent failure of the PNIS has been well documented by, among others, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. There were huge delays, poor communication, and subsidies that never arrived. Regional development and infrastructure never materialised either. A farmer in Tumaco, Nariño, told us, ‘We eradicated [coca] and that was it. To this day, we haven’t received one single support payment. We planted cocoa instead, but that cocoa isn’t generating any income yet. Sometimes we eat two meals a day, sometimes just one.’

They finished off our food – the maize, the yucca, everything!

-Farmer from Puerto Asis

Then, instead of the promised subsidies and infrastructure, the army showed up to destroy the coca crops – and any other crops in the vicinity. One farmer from Puerto Asís, Putumayo told us, ‘They would fumigate sometimes every 15 days in our village… they finished off our food – the maize, the yucca, everything! There was nothing left. We were left without food, the only thing we had left were a few corners of coca.’

And forced eradication isn’t just destroying livelihoods, it’s killing people. Our research documented 96 violent clashes between rural communities and state forces linked to forced eradication between 2016-2020. 42% of those reported incidents have been since March 2020, with deaths recorded in 6% of cases.

The coca farmers we spoke to tell us that when they ask why there are delays in receiving subsidies, they’re told there’s no money. So, it seems there are no funds to implement the programme, but plenty to resource forced eradication – which doesn’t come cheap. More than this, under pressure from the US, President Duque has not only pledged to ramp up forced eradication, but is looking for ways to bring back aerial fumigation, despite it having been suspended by Colombia’s Constitutional Court in 2015 due to environmental and health harms.

Last month, a court in Cauca in southwest Colombia ordered the army to stop forced eradication until they could prove that the voluntary crop substitution programme has failed. A national organisation that represents coca farmers is now working to get this order extended to the whole country.

If they succeed, this will mean a much-needed respite for the hundreds of thousands of peasants who are living in constant fear that their livelihoods will be destroyed by forced eradication, not to mention the violence that accompanies the process. ‘It’s not just Covid-19 that ends the lives of peasants’, said one community member in Cύcuta, Norte de Santander, ‘there’s another pandemic that is far worse. This is the forced and violent [action] by the army.’

A national suspension of forced eradication, however, could mean a real boost for the crop substitution programme and contribute to making peace a reality in Colombia.

Can PNIS work? Yes, there’s a real chance that it can. But it needs to be given a chance. The farmers are on board (in the words of a coca farmer in Puerto Asís ‘if there were other opportunities, no one would work with coca because it’s enslaving’). And the national suspension of forced eradication may be the incentive or leverage needed to get the government to give it a real go.

But illicit drugs aren’t just about policy, they’re about politics too – national and international. So, there’s an important role for international actors in this, especially those that invested a lot of money, time and expertise into supporting peace negotiations in Colombia, which were a really important part of that process.

The government claims it is implementing PNIS. The coca farmers claim it is not. We need independent arbiters to look at the evidence, and see what can be done to support the implementation of the peace agreement.

We need those countries that have supported peace in Colombia to follow up and support implementation, by speaking and listening not just to the government, but also to the Congress, NGOs, academics, and social movements. This could be crucial in turning the tide of violence.