‘Resisto, luego existo’, the new exhibition at Bogota’s Centro de Memoria, Paz y Reconciliacion opens to the public with documentaries about centres of resistance around the country.

Afro and Indigenous Colombians building peace in Putumayo in the midst of an armed conflict; Bogota’s ollas comunitarias (food banks) and mutual support in the streets during the 2021 paro nacional and ensuing mobilisations; the Indigenous Councils Association in Villagarzón, Putumayo resisting state abandon, violence and the Covid pandemic; Kamsá Biyá people using art and speech to claim their rights in Sibundoy, Putumayo; the armed threat to Indigenous leaders, especially young people, who are assassinated by armed groups to intimidate and quell leadership in the Indigenous Movement in Cauca; repression and state violence in San Bernardo, Nariño during the paro nacional and the lack of opportunities for young people outside of the cities.

These are some of the themes in the documentary film ‘La Gran Juntanza: La crónica de un país en resistencia’ (The great gathering: chronicle of a country in resistance), from Elegante Films’ series Historias Bien Jaladas. The film is part of ‘Resisto, luego existo’ (I resist, therefore I exist), a new exhibition at Bogotá’s Centre of Memory, Peace and Reconciliation, which opened to the public on Thursday 24 March.

‘La Gran Juntanza’ was made in association with Asociación MINGA, a decentralized, alternative association mainly made up of individuals from Indigenous communities in the south of the country, who protect human rights in Colombia and fight against a humanitarian and environmental crisis. The MINGA association came about around the same time as the 1991 Constitution, and many of its members feature in the film, soundtracked by songs from resistance singer La Muchacha Isabel.

The film documents the initiatives Colombians are developing to rewrite their country’s history, promoting peace and respect for each other and their environments. In one interview, a Kamsá Biyá leader tells the filmmakers ‘Tenemos que seguir denunciando la guerra’ (we must continue to denounce the war). But this comes at a huge cost to communities. A shocking tribute at the end of the film commemorates the lives of many of the leaders interviewed, who have since been killed.

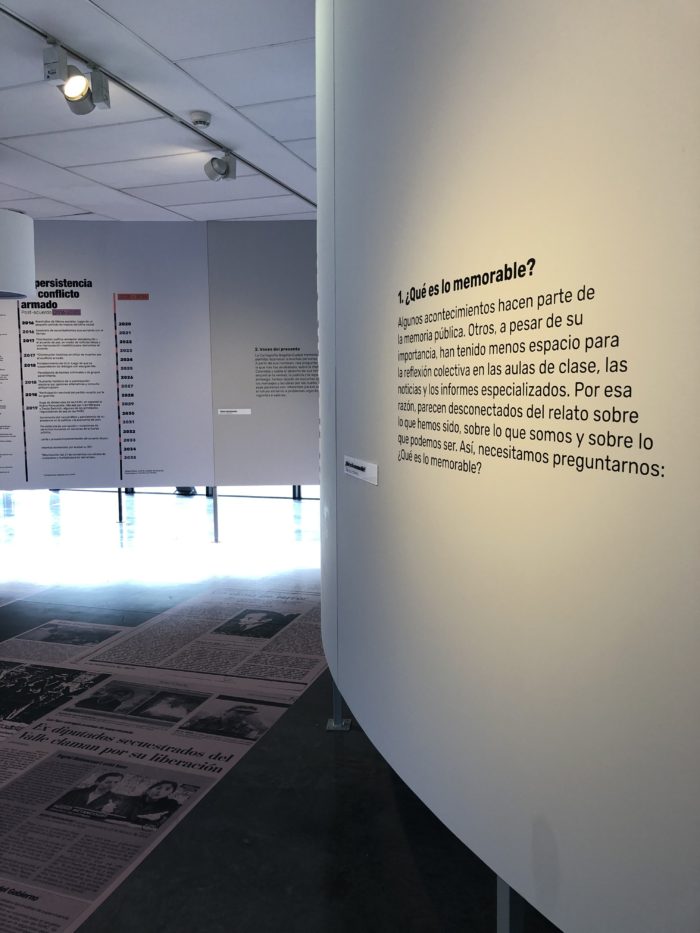

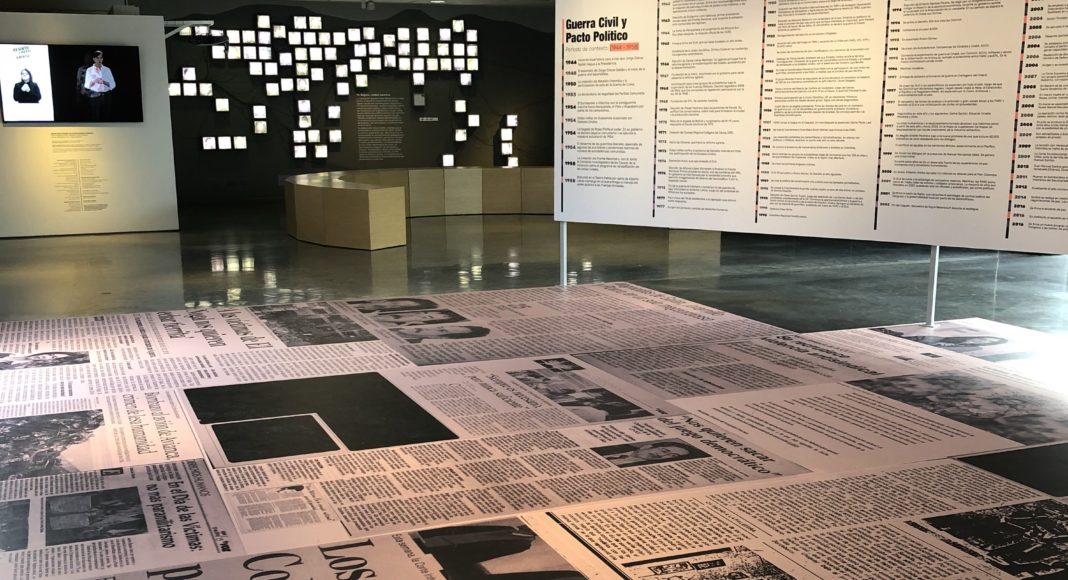

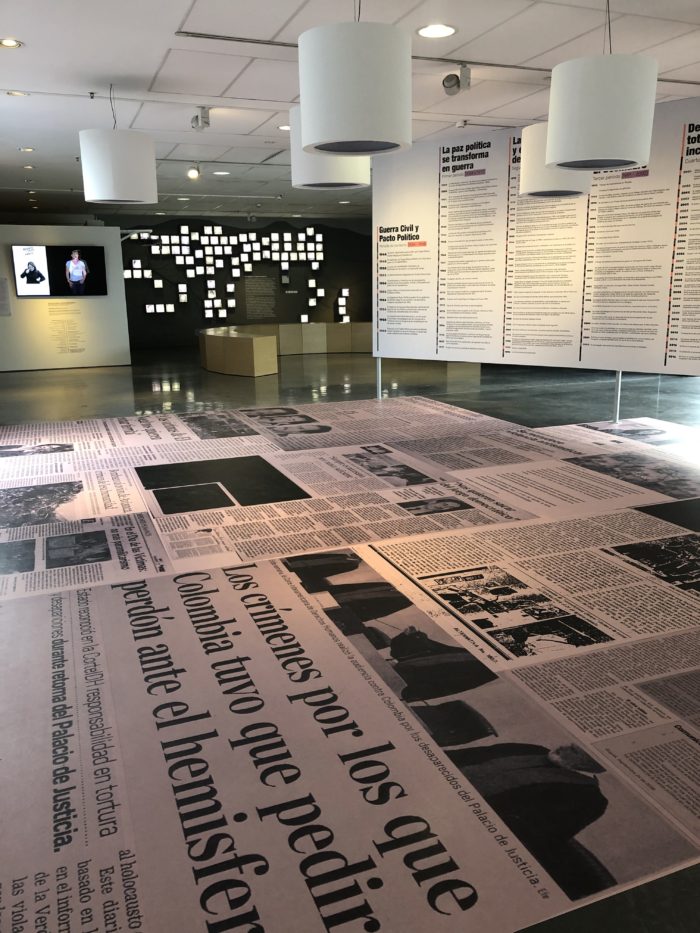

The exhibition, however, of which the film is a part, suffers from the same shortcomings as the Centro de Memoria, Paz y Reconciliación itself. A centralized museum, it looks from Bogota outwards, highlighting the same well-known figures and historic dates in the history of Colombia’s years of violence, but fails to present the voices of everyday people across the country today – suffering, resisting, building peace. The exhibition includes the same images of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, Jineth Bedoya and Pablo Escobar that feature in every narrative of Colombia’s violent history, and the same ‘key’ moments of Colombia’s past. This keeps the country a prisoner of a narrative that ignores people’s daily struggles for change.

A timeline of events from 1944-2019 fails to bring us up to the present and omits important details from the last two years: the pandemic and its effect on the peace process, the scores of leaders killed, the social mobilisations and widespread state violence and repression.

A wall showing points of memory within the capital city attempts to commemorate the victims of police violence, like Dilan Cruz (student killed by an ESMAD projectile in November 2020) , Nicolás Neira (killed by ESMAD riot police May 2005), Diana Turbay Quintero (killed by the Colombia National Police during a botched rescue attempt in January 1991) and Sandra Calatina Vásquez Guzmán (raped, tortured and killed by a policeman in a police station at nine years old in 1993). But there could be more mention of those wounded and killed during the 2021 paro nacional, and of the extreme violence in Cali and specifically Siloé.

A chalk wall invites visitors to note down the reasons they resist: for those who are no longer here; for the environment; for their respect for life; for women. Smaller screens play interviews with some of the ‘Madres de Soacha’ (Madres de Falsos Positivos de Soacha y Bogotá, MAFAPO), an association of mothers, wives, children and sisters of men illegitimately killed by the Colombian Police and military in the ‘false positives’ scandal of 2006-2009 under Álvaro Uribe’s leadership. When the women felt there was no space where they could express their resistance, they decided to use their own bodies, with tattoos commemorating their children’s lives and their fight for justice.

Andres Juajibioy, interviewed in La Gran Juntanza explains: ‘Often a photo or a video cannot convey what is behind a cause, behind its collectivity. But behind the cause is the mother who looks after the children, those who source and prepare food for those protesting, everything we share communally in order to unify ourselves under one voice.’ La Gran Juntanza tries to bridge this gap.

The team behind the Centro de Memoria, Paz y Reconciliación, led by José Antequera, believe the exhibition to be a fundamental tool for education, reflection and dialogue around the recent history of the country, which has been marked by armed conflict and political violence. But what does it contribute to changing this narrative?