By Javier Farje, LAB

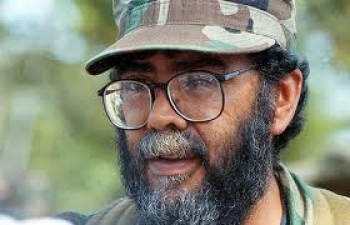

Alfonso CanoThe killing of Alfonso Cano (real name, Guillermo León Sáenz Vargas, born in Bogotá, 1948), the top leader of Colombia’s main guerrilla movement (the other one being the much smaller ELN – National Liberation Army) is, without a doubt, a political victory for President Juan Manuel Santos. It will help him move away from the perception that he is a kind of lackey of his mentor and predecessor, Alvaro Uribe. One way or another, it may also be a political turning point for the FARC.

Alfonso CanoThe killing of Alfonso Cano (real name, Guillermo León Sáenz Vargas, born in Bogotá, 1948), the top leader of Colombia’s main guerrilla movement (the other one being the much smaller ELN – National Liberation Army) is, without a doubt, a political victory for President Juan Manuel Santos. It will help him move away from the perception that he is a kind of lackey of his mentor and predecessor, Alvaro Uribe. One way or another, it may also be a political turning point for the FARC.

Reactions in Colombia have been mixed. There are, at the moment, two schools of thought: one maintains that this is the beginning of the end of the FARC, while the other adopts a more cautious approach, saying that the guerrillas have the capacity to regroup and fight back, as they have done so often in the past. President Santos’s position lies somewhere in between.

Andrés Gonzales, a former government negotiator and current governor of Cundinamarca, believes that the FARC is nearly finished. He insists that the state has a presence across the country that it did not have before Alvaro Uribe became president in 2002. To some extent, this is true. Until a decade ago, the state had a negligible presence in the most remote regions of Colombia, even being totally absent in some areas. The guerrillas filled the power vacuum, especially in the Amazonian territories bordering Peru, Ecuador and Venezuela. Uribe changed all this. Using a combination of military might and political manoeuvring, he made sure that the state was present all over the country.

But not everyone shares the idea that the FARC is on its last legs. For Iván Cepeda, a human rights activist and now a member of the Colombian parliament for the centre-left Alternative Democratic Pole, the FARC “has 50 years of existence and can take hits [like the death of Alfonso Cano].”

President Santos has tried to avoid any kind of triumphalism but is trying to seize the initiative. He has sent a clear message to the rebels: demobilise or your members will end up “in jail or in a grave”. As Santos himself must know, this strategy is unlikely to succeed, at face value. “It is absurd to believe that, suddenly, the FARC will publish a statement saying it is giving up its weapons”, says Camilo Gómez, the top government negotiator during the failed peace process undertaken by President Andrés Pastrana in 1998. “The FARC has an institutional structure that is stronger than any of its leaders. Its guerrilla fighters know that their destiny is to die in combat, and it is an honour for them”. He warns that Colombia will face “a time of intense military activity”.

It is absurd to believe that, suddenly, the FARC will publish a statement saying it is giving up its weaponsDaniel García-Peña, another former government negotiator, agrees. “It [the FARC] has shown a great capacity to resist and these hits will strengthen its spirit. To believe that the death of Cano means the end of the FARC is naïve. The conflict will continue.” Indeed, he believes peace talks may be even more difficult, for the FARC has lost an ideological leader who wanted to negotiate. It seems that even members of the military agree with this analysis. General Gustavo Rosales, director of the Institute of Geostrategic Studies at the Nueva Granada Military University, says that the FARC is “neither near to surrendering nor close to starting a negotiation process”.

It is absurd to believe that, suddenly, the FARC will publish a statement saying it is giving up its weaponsDaniel García-Peña, another former government negotiator, agrees. “It [the FARC] has shown a great capacity to resist and these hits will strengthen its spirit. To believe that the death of Cano means the end of the FARC is naïve. The conflict will continue.” Indeed, he believes peace talks may be even more difficult, for the FARC has lost an ideological leader who wanted to negotiate. It seems that even members of the military agree with this analysis. General Gustavo Rosales, director of the Institute of Geostrategic Studies at the Nueva Granada Military University, says that the FARC is “neither near to surrendering nor close to starting a negotiation process”.

However, this does not mean that FARC has not been weakened. In recent years, it has suffered the biggest losses ever in its long history. In late March 2008, Manuel Marulanda, founder and historic leader of the FARC, died of natural causes. Days earlier, Colombian troops had entered Ecuadorian territory and killed Raul Reyes, a member of the guerrilla’s secretariat and the man responsible for its international relations. Juan Manuel Santos was a hardliner defence minister at the time. More recently, in September 2010, after Santos had become president, the FARC suffered a further major blow: its military top commander, Jorge Briceño, better known as Mono Jojoy, was killed during a military operation in the Meta Department, south of the capital, Bogotá.

The death of its top leaders has shaken the organisation to such an extent that its composition has changed: its earlier vertical structure has been abandoned, with the emergence of relatively autonomous regional groupings. These groupings have great flexibility to move in the areas they control, but it also makes the FARC as a whole more fragmented and thus more vulnerable to targeted military operations by the army.

To make things worse, the FARC has also lost a great deal of the earlier support it received from indigenous communities. The Colombian human rights lawyer Eduardo Carreño told LAB that these communities have suffered as a result of FARC attacks: “When the FARC attacks military posts in these areas, it uses ‘cylinder bombs’ [metal barrels filled with explosives]. When the guerrillas throw these cylinders, they have a devastating effect on the fragile houses of peasants and indigenous peoples.” FARC today has only 7 – 9,000 members, half the number of militants it had a decade ago Even so, the rebels have never shown any intention of surrendering. It still controls remote territories in the Colombian Amazon.

Information from some of the demobbed guerrillas seems to confirm this analysis. They say that many fronts have split into small groups and are wandering in the jungle without much contact with the top commanders, because of fears that their communications will be intercepted and that drone planes will find their camps. As a result, John Marulanda, a security expert, predicts that the fight back will take the form of a succession of relatively uncoordinated armed actions in Catatumbo, Arauca, Putumayo, Cauca and Nariño.

The question now is who will succeed Manuel Cano, and how the new leader will try to raise the morale of his troops. At the moment there are two candidates to become the third leader in the FARC’s history: Rodrigo Londoño, aka ‘Timochenko’, and Luciano Marín Arango, aka ‘Iván Márquez’. Timochenko controls the highlands of Perijá, in the border with Venezuela. Márquez is the head of the North Block and was involved in the failed peace process with former president Andrés Pastrana. Both candidates combine the political and military tendencies within the guerrillas and some analysts in Bogotá believe that they may try to find a way to start a dialogue with the government.

According to military analysts quoted by the Colombian daily El Nuevo Siglo, Alfonso Cano wanted to be a historic leader like Manuel Marulanda, a politician like Raúl Reyes and a military commander like Mono Jojoy, all in one. According to the same sources, he was still trying to consolidate his image at the time of his death. Whoever succeeds him will also need to balance these tendencies so as to ensure that demoralisation does not spread among the rebel ranks.

Santos

President Juan Manuel Santos vs former President Alvaro Uribe: a bitter divorce.The big winner is, without a shadow of the doubt, Juan Manuel Santos, and for him the timing of Cano’s death could not be better.

President Juan Manuel Santos vs former President Alvaro Uribe: a bitter divorce.The big winner is, without a shadow of the doubt, Juan Manuel Santos, and for him the timing of Cano’s death could not be better.

Shortly after he was elected, the former Defence Minister said he would be his own man, firmly denying the idea that he would be some kind of transitional president, elected to pave the way for a return of his mentor, Alvaro Uribe. He seems to be following his word and Uribe, clearly irritated, is not making things easy for his successor. Almost from the start of the Santos administration, Uribe criticised him for failing to establish a coherent security strategy and also claimed that there was a climate of demoralisation in the military. Santos has fought back, saying that the killing of Mono Jojoy and other guerrilla commanders prove that Uribe is wrong.

There have been further clashes, over key issues. In what appears to have been a manoeuvre to allow him to exert full control over the security forces outside any form of accountability, Uribe took direct charge of the Administrative Security Department (DAS), the infamous Colombian intelligence agency, from his presidential palace. During his term of office the DAS was responsible for a campaign of intimidation against the judiciary and was also infiltrated by far-right paramilitary elements. Indeed, in October 2011, the former head of DAS, Jorge Noguera, was sentenced to 25 years in prison for his collusion in the activities of death squads.

In early November, Santos had the temerity to announce the dismantling of DAS. Needless to say, the Uribe camp strongly criticised this decision, saying that Santos was getting rid of an agency that was vital to the armed forces in their fight against the guerrillas. However, to Santos’s evident delight (though he has been very careful in what he has said), less than a week later, these same armed forces killed the head of FARC, without the help of the allegedly irreplaceable DAS.

Because of measures like this, the relationship between human rights organisations and the government has improved since Santos took over. There are, however, aspects of his administration that these organisations are still highly critical of. As Eduardo Carreño told LAB, the government has done nothing to challenge the presence of the US military and civilian contractors in the country, nor has it interfered with the US military bases in the Amazon. Carreño says that the state has no control over the activities of the US personnel, because they are not even the subject of normal immigration procedures.

The death of Alfonso Cano is undoubtedly an opportunity for Santos but also a risk. Will he try to finish off the FARC? Or will he try, instead, to create a climate that would lead to a meaningful dialogue with the rebels? It’s too soon to predict what will happen. What is clear, however, is if Santos can somehow use Cano’s death to move the country closer to an end to this long conflict that to so many people, inside and outside Colombia, seems an out-dated hangover from an earlier phase in Latin America’s history, he will construct for himself a much more important place in the history of this troubled country than the one occupied by his predecessor.