While this article is global in scope, LAB is publishing it because all of the many interesting issues it raises are common to Latin American countries also. Duncan Green worked as a researcher-writer at LAB from 1989 to 1997 and was author of a number of LAB books, including Faces of Latin America. He is also author of the influential blog From Poverty to Power. He is currently Senior Policy Adviser to OXFAM and Professor in Practice at the London School of Economics. The author would welcome suggestions and comments to d.j.green@lse.ac.uk

This paper is a way to organize my thoughts about what has been an emerging theme within the last few days in discussions of the pandemic. The coverage is vast, so I have had to focus – on the longer-term impact of the Covid-19 outbreak on political, economic and social systems, and its particular impact on the aid sector, and progressive advocacy, whether by civil society organizations or others.

I deliberately start with a theory of change – thoughts on how the wider world might change as a result of Covid-19 and the response. Only then do I move on to some brief thoughts on matters closer to home – the impact on aid and advocacy. I would appreciate comments, suggestions and references (to d.j.green@lse.ac.uk). [1]

Contents

1. Epidemics as Forks in the Road

The Black Death, which wiped out up to half of the English population in the mid-14th Century was also a fork in the road of European history. In Western Europe:

‘The massive scarcity of labour created by the plague shook the foundations of the feudal order. It encouraged peasants to demand change’ (Why Nations Fail, p. 98).

In subsequent decades, wages rose and the government tried to defend the status quo, triggering the Peasants Revolt of 1381, which captured most of London. Although it was put down, the government abandoned its efforts, and a free labour market stayed for good.

In Eastern Europe however, the landlords responded to labour shortages with repression and succeeded in creating what became known as the ‘Second Serfdom’, including increasing amounts of forced labour. The diverging paths in response to the Plague reflect small differences in initial conditions like population density that subsequently led to growing divergence over time, a phenomenon known as path dependence.

The Black Death was just one prominent example of what political scientists call ‘Critical Junctures’ (CJs). Asked what he most feared in politics, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan reportedly replied in suitably patrician style, ‘Events, dear boy’. Such ‘events’ – be they scandals, crises or conflicts – can disrupt social, political, or economic relations. They throw the status quo and power relations into the air, and in so doing can open the door to previously unthinkable reforms. They act as a fork in the road, a moment of change in the path dependent evolution of political institutions and systems, which move them onto one path, and not others.

Importantly for the current crisis, little of this is predictable. The small differences (butterfly’s wings) that lead to different eventual outcomes (tornados) can only be discerned after the event, if then.

The Black Death is not the only example. In Plagues and the Paradox of Progress, Thomas Bollyky argues that health shocks have had other major impacts on institutions and society. ‘Encounters with infectious disease have played a key role in the evolution of cities, the expansion of trade routes, the conduct of war and participation in pilgrimages.’

According to Bollyky, ‘prevention and control depends on the cooperation of people and governments… Under pressure from social reformers and angry citizen mobs, governments of wealthy countries in the 19th Century constructed water and waste management systems, adopted housing codes and food regulations, promoted personal hygiene and entered into the first international health treaties.’

In the last 100 years, the two greatest pandemics have been the Spanish flu and HIV/AIDS. The flu outbreak of 1918-20 took hold in the final months of World War One and claimed anything up to 100m lives (10 times more than were killed in the war itself). Yet its political and institutional impact is hard to distinguish from the response to the War itself.

To date, HIV/AIDS has killed some 40m people. Researchers credit it with ‘transforming global health, elevating the issue as a foreign policy priority and helping to raise billions of dollars for researching, developing, and distributing new medicines.’ (Bollyky) and ‘also introducing a new paradigm for the involvement of affected individuals and communities and changed the dynamics between caregivers, the pharmaceutical industry, public health establishment and international organizations, and affected communities.’ (Piot, Russell and Larson). However, I am unaware of any research on its broader political and social impact and would welcome suggestions.

Other precedents for crises as CJs that are often discussed include the great 1958-62 famine in China, following the misnamed ‘Great Leap Forward’; the Bengal famine of 1943, the collapse of the USSR, the 9/11 attacks, two World Wars and the Global Financial Crises of 1929 and 2008. Some (very) broad lessons from the last of these:

- Badly designed responses to crises, such as the punitive settlement agreed after World War One or the kleptocratic free-for-all that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, can put countries and continents on deeply negative pathways. Equally, well designed responses, such as the setting up of global institutions including the United Nations after World War Two, can have a much more beneficial long-term impact.

- CJs are not single moments. Seen through the telescope of historical distance, they may seem like points in time, but the reality when you are living through them (as we are now) is both more extended and much messier. During a crisis, what seems important in the immediate may subsequently fade into irrelevance. In the early days of the 2008 financial crisis, the rise of the G20 appeared to promise a new order of improved global co-operation and the eclipse of the Northern monopoly of the G7. But the G20 rapidly faded into insignificance; the deeper impact that emerged was of an erosion of trust and institutions and the rise of populism, leading to something closer to a vacuum of leadership at a global level (the ‘G zero’).

Given this, it is important for activists in the present crisis not merely to latch onto the first issue that surfaces in the early stages of a CJ, nor look only through the blinkers of their personal or institutional pre-crisis priorities. Instead they need to develop a form of ‘lateral vision’ that spots new issues and opportunities for change as they emerge – new waves to ride in the search for progressive change, as well as new threats that must be confronted.

In responding to a crisis, it is also worth distinguishing between short term actions (responses to the crisis; issues of inclusion and exclusion; unintended consequences) and the long term (shaping the recovery; responding to big political, normative and ideological shifts). Right now, most attention is understandably focussed on the short-term responses, but this paper instead explores the possible longer-term impacts.

2. Covid-19 and Global Inequality

The virus may assail human beings irrespective of their rank and privilege, but what happens next is acutely influenced by where they sit within a large range of inequalities.

As with HIV/AIDS, poverty is a critical ‘pre-existing condition’. In all countries, poor people have worse health, and so are more vulnerable to the disease; they live in more cramped conditions and so find it harder to ‘self-isolate’; they often work in informal, unregulated jobs that are likely to be overlooked by government safety net schemes.

In addition, some groups find it particularly difficult to follow guidance predicated on stereotypes of nuclear families with ample private space, able to self-isolate. Overcrowded refugee camps, prisons or migrant workers hundreds of miles from home are particularly vulnerable.

Poor women also face particular difficulties: in self isolation they may not be able to escape from abusive partners; as traditional custodians of the ‘care economy’, their burden of care is likely to shoot up during and after the outbreak.

Inequality between countries similarly ratchets up the effect on the poor – poor country governments are less able to respond, whether economically or politically, especially in so called ‘fragile and conflict-affected states’, where governments are often either absent or predatory.

Although this paper does not explore the immediate impact in detail, it is important to keep these inequalities in mind when discussing the medium and longer-term consequences and responses.

One word of caution: although the immediate impact of the crisis seems almost certain to increase inequality, the longer term impact is less certain. There are some historical grounds for expecting some reduction in inequality to result. Thomas Piketty in his best-selling book Capital in the 21st Century highlighted the impact of world wars in wiping out accumulated capital and reducing wealth inequality. In his book The Great Leveller, historian Walter Scheidel found that over a much longer term, plagues have played a similar role: ‘Pandemics served as a mechanism for compressing inequalities of income and wealth.’ (p. 335)

3. The Covid-19 Critical Juncture: Possible long-term impacts

Covid-19 will act as a major stress test of current assumptions about how the world works, and our institutions and practices. They may not come out of it very well, according to Ranil Dissayanake: ‘We have allowed the economic model in much of the west to outsource risk, uncertainty and insecurity to labour through changes in firm structure and inter-relationships. This may have allowed greater expansion in the economy and stimulated innovation, but it has not been matched by innovation in social protection or support for the vulnerable, and if Covid is a stress test, this is the area I fear we are going to fail most miserably.’

What follows are some thumbnail portraits of potential areas of political, social and economic impacts, often raising more questions than answers.

Politics

Covid-19 shines an unforgiving light on all political leaders and systems, exposing their strengths and weaknesses in preparing, detecting, responding and (eventually) leading the recovery from a crisis. All political systems are struggling to cope, and there are alarming signs of the USA and China, in particular, seeing this as a moment to prove the superiority of their own system/blame each other, rather than build new forms of cooperation, as has been the case with some previous CJs.

At a national level, Nic Cheeseman set out In a twitter thread three different mechanisms through which Covid undermines democracy:

‘The most obvious mechanism is that authoritarian leaders use COVID19 to ban rallies and protests, and in some cases cancel elections, eg by declaring states of emergency.

A less obvious mechanism is that authoritarian leaders simply do more of what they have always been doing in the knowledge that no one is paying attention. For these leaders Covid19 represents a good period to bury bad news.

Those two mechanisms are employed by what Brian Klaas calls “counterfeit democracies”. But the third mechanism is more universal and less intentional, at least on the short term. The assumption of emergency powers by governments creates long-term problems because these powers – and the new technologies developed to respond to crises – are rarely fully reversed when the crisis is over. This is the ‘ratchet effect’ and it is far more insidious.’

These debates also reflect deeper shifts in the tectonic plates of political debate. The war for Boris Johnson’s ear is in large part a battle between notions of individual and collective rights. The latter is the clear winner in terms of confronting the virus, but will that victory be temporary or lead to a longer-term shift away from liberal individualism? And how will that affect the rise of populist leaders such as Narendra Modi or Donald Trump, whose erratic leadership has been badly exposed by the crisis? The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 accelerated the erosion in trust in institutions and leaders, contributing to Brexit and the rise of populism: will the disastrous performance of populist leaders, contrasted with the successful reliance on science and institutions to keep us safe, reverse that erosion?

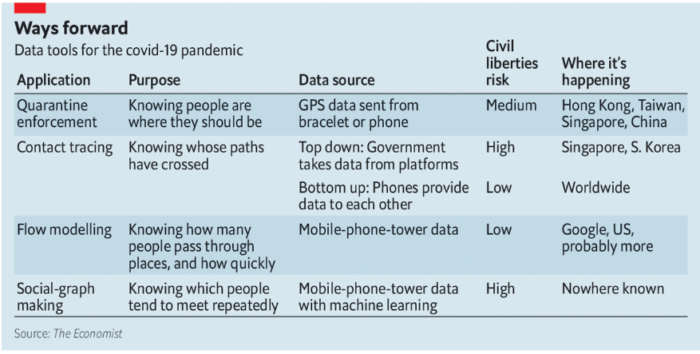

Nowhere has the encroachment on democratic and civic space been more apparent than over the issue of surveillance. Data protection has been swept aside in many countries in the interests of tracking and containing the pandemic (see Economist summary table, above), but as Yuval Noah Harari told Channel 4 News on 27th March:

‘When it’s over, some governments will say ‘yes, but there is a second wave, or Ebola, or just flu’ – the tendency will be to prolong surveillance indefinitely – the virus could be a watershed moment. And now it is under the skin – governments are not just interested in where we go, or who we meet, but even in what’s happening inside our bodies – our temperature, blood pressure, medical condition.’

Writing in Global Policy, Nathan Alexander-Sears fears that ‘this expansion of state biopower will become an enduring feature of a new biopolitics for the purposes of “security” and excavates an extraordinarily prescient passage about the politics of quarantine, from Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975):

First, a strict spatial partitioning… Each street is placed under the authority of a syndic, who keeps it under surveillance; if he leaves the street, he will be condemned to death.… This surveillance is based on a system of permanent registration: reports from the syndics to the intendants, from the intendants to the magistrates or mayor. At the beginning of the ‘lock up’, the role of each of the inhabitants present in the town is laid down, one by one; this document bears ‘the name, age, sex of everyone, notwithstanding his condition’: a copy is sent to the intendant of the quarter, another to the office of the town hall, another to enable the syndic to make his daily roll call. Everything that may be observed during the course of the visits—deaths, illnesses, complaints, irregularities is noted down and transmitted to the intendants and magistrates. The magistrates have complete control over medical treatment; they have appointed a physician in charge; no other practitioner may treat, no apothecary prepare medicine, no confessor visit a sick person without having received from him a written note ‘to prevent anyone from concealing and dealing with those sick of the contagion, unknown to the magistrates’. The registration of the pathological must be constantly centralized. The relation of each individual to his disease and to his death passes through the representatives of power, the registration they make of it, the decisions they take on it.

Watching some of the more draconian responses 45 years on, all that Foucault missed was the way digitization has made this process both easier and more efficient.

The Global and Institutional Legacy: Crises can resemble political earthquakes, releasing pent up forces in the tectonic plates of politics, triggering a rapid shift to a new balance of forces. Given its particularly chaotic handling of the pandemic to date, and the level of internal division on display, could Covid-19 become a ‘Suez moment’ for the USA, a critical juncture in its long term loss of global hegemony, as the Suez crisis was for the UK?

In addition to the fate of particular governments and leaders, the pandemic is likely to leave some kind of institutional legacy. Will it be a new wave of global and national collective action institutions, as after World War Two? Although this would be the logical response to the shock of a global pandemic, eg beefing up the WHO’s role in to share medical technology and rapidly coordinate pandemic and other responses, the level of ‘othering’ currently on show as governments blame each other and shut borders on the flimsiest of medical grounds suggests this is not a given.

The way we frame discussions about policy: As Ranil Dissayanake suggests, the current crisis could lead to a change in the framing of what constitute desirable policies: if resilience to shocks is the aim, then moving from a focus on efficiency to encouraging redundancy (e.g. having multiple failsafe mechanisms, even if that entails greater expense) makes more sense; it may also require a move from building ‘maximizers’ to ‘stabilizers’ such as (in social policy) social protection, universal basic income, improved sick and unemployment benefits or other automatic social safety nets, that kick in early on in a crisis to smooth out the bumps.

Society

Social norms – the expectations that guide assumptions and behaviour about how we relate and treat our fellows, can change in the aftermath of a CJ. This can have impact on policies and advocacy, for example in the way the 2008 financial crisis contributed to increased concern over levels of inequality. But they can also affect more day to day social interactions.

Gender: The crisis is heavily gendered, both in impact and response. Women comprise the majority of health and social care workers and are on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19. Mass school closures have particularly affected women because they still bear much of the responsibility for childcare. Women already do three-times more unpaid care work than men – and caring for relatives with the virus adds to the burden. In many developing countries, the informal economy (often predominantly female) is receiving much less state attention than waged work. There is a clear risk of increased violence against women as a result of self-isolation.

What is not yet clear is whether this will lead to longer term rethinking of, for example, the importance and policy priority given to the care economy. World War One was followed by an upsurge in women’s emancipation, whereas after World War Two, women were driven out of the workforce and back into the home. Which will it be this time?

Solidarity: The extraordinary mutual aid response and explosion of volunteering in many countries could be a turning point in many people’s relationship with their communities. It seems unlikely that they will all disappear once the virus is defeated – some will morph into social movements, perhaps in the way that the civic action in response to Mexico’s 1985 earthquake sowed the seeds for new social movements that ultimately led to the overthrow of Mexico’s one party state.

That solidarity could also be reflected in a new ‘intergenerational social contract’ – young people are concerned and looking after vulnerable older people in the crisis, but what will be the wider impact on inter-generational equity? In a paper on the long term impacts of Covid-19, Alex Evans and David Steven argue that:

‘The young are being asked to sacrifice and to step up for the old. The vast majority accept that their parents and grandparents are rightly our immediate priority – but solidarity between the generations must work both ways. Redistribution from older people with assets is part of the answer.

This is also the time for older generations to support the decisive action on climate change and on more sustainable, equitable, and resilient patterns of development that many younger voters desperately want.’

But there are more depressing potential impacts too. I am struck by my own reactions as I pass people in the street and see them as potential sources of infection, rather than individuals. My brother rails against London as a cesspit of infection. Will Covid-19 further erode our sense of a common humanity?

From Analogue to Digital Conversations?: My 96 year old mother (or at least the top of her head) is now communicating with me via FaceTime; I have finally had to learn to use Zoom properly and last week spent 7 hours talking to students online in a range of formats. It seems likely that some aspects of this mass shift from analogue to digital interaction in consuming, connecting, collaborating and organizing will prove irreversible.

Space as a Human Right: At a personal level, the sudden limitation/removal of public space through lockdown makes us acutely conscious of space as a public good. How much private space we have access to will determine how painful or otherwise the next few months will be. Will the crisis lead to new priority and attention being given to the right to space?

Travel and Movement: Environmentalists are celebrating an effective end to carbon emissions from air and road transport, and pleading for such shifts to be irreversible. Business travel should be replaced by Zoom chats. Whether this will happen in the work space will depend on the lockdown experience of the quality and cost of online interaction (and people learning to go on mute), compared to the face to face version. But in leisure, it is hard to see why tourism and associated travel should not revert to its pre-existing growth trend after the crisis passes, unless governments choose to pass significant new legislation to deter it.

The Economy

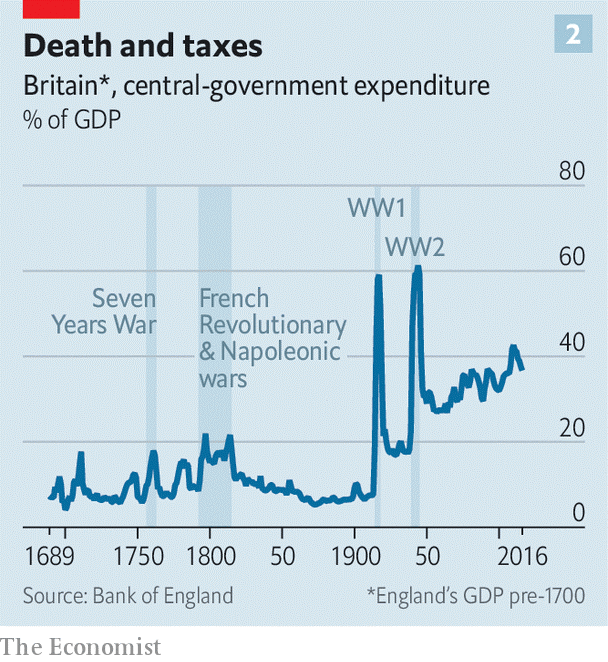

The extraordinary impact on the global economy (far more serious than that of the 2008 financial crisis) hardly needs rehearsing here. In the longer term, The Economist believes that

‘Perhaps the most important lesson of 500 years of history, however, is that nothing has helped boost state power in Europe and America more than crises.’

It believes that ‘the world is in the early stages of a revolution in economic policymaking.’ Austerity has gone out the window; ‘whatever it takes’ is on the lips of the world’s leaders. It even sees a possible knock-on effect: ‘If central banks promised to fund the government during the coronavirus pandemic, they might ask, then why shouldn’t they also fund it to launch an expensive war against a foreign enemy or to invest in a Green New Deal?’

This may of course be wishful thinking – magic money trees abounded during the global financial crisis, but rapidly disappeared in the upsurge of austerity that followed.

The impact on low and middle income countries has received less media attention in the North. By 28th March, The Economist was reporting ‘Foreign investors have pulled $83bn from emerging markets since the start of the crisis, the largest capital outflow ever recorded.’ Remittances from migrant workers – often a crucial lifeline that globally comes to four times the volume of aid – are also bound to fall in the global shutdown.

4. What does this mean for Aid?

That will have enormous implications for aid and economic policy. In the short and medium-term, there will be a desperate need for debt relief that by one estimate could free up $50bn over the next two years to combat the pandemic and finance the recovery in poor countries. In the longer term, development cooperation will have to play its part in ensuring that the post-Covid recovery ‘leaves no-one behind’, for example by addressing the generational damage caused by the lockdown of most of the world’s schools.

Aid flows act as a stable source of capital when more volatile channels go into reverse, and will provide an important lifeline to the poorest economies.

There are grave concerns about the implications of the crisis for the existing work of aid agencies. They will be forced to respond to what could become an extraordinary humanitarian situation – imagine the impact of Coronavirus running riot in overcrowded refugee camps with few facilities – and also to maintain work on existing priorities. A survey by the New Humanitarian concluded ‘attention and resources could shift away from some of the world’s most vulnerable populations even as COVID-19 presents a new threat to them.’ A Caritas worker in Venezuela told the website ‘we risk becoming a forgotten crisis’.

An MSF post captured the prevailing mood:

‘As MSF, we will also need to manage the gaps we will face in staffing our other ongoing emergency projects. Our medical response to measles in DRC needs to continue. So too does our response to the emergency needs of the war-affected communities of Cameroon or the Central African Republic. These are just some of the communities we cannot afford to let down. For them, COVID-19 is yet another assault on their survival.

This pandemic is exposing our collective vulnerability. The powerlessness felt by many of us today, the cracks in our feeling of safety, the doubts about the future. These are all the fears and concerns felt by so many in society who have been excluded, neglected or even targeted by those in positions of power.’

Over the medium term, there will be a war for hearts, minds and crisis-constrained wallets between inward looking ‘charity begins at home’ mindsets and the counter-argument that the crisis clearly shows that global problems do not stop at borders – health (like climate change, migration and many other challenges) is a collective action problem that requires collective solutions, including aid. It is worth remembering that public and political support for aid did not collapse after the 2008 financial crisis, despite dire predictions at the time.

Searching for a silver lining, Chris Roche argues that the Covid-19 crisis could enable the aid business to finally meet its failed promises to localize funding and control in the hands of national organizations in developing countries. Expats will not be able to travel (whether through visa restrictions or their own organizations health and safety procedures). In their absence ‘Local services and people will step up, as they do in every emergency, only this time their efforts are less likely to be camouflaged, or indeed undermined, by their international partners.’

Roche argues that this temporary, crisis-driven localization could become permanent, provided ‘creating the physical and human infrastructure which allows for the arm’s-length, carbon-friendly, at-a-distance support that enables the emergence of locally led processes.’

5. Some Implications for Advocacy and Campaigns

The crisis has also provided a stress test for both the style and content of a range of NGO advocacy on issues including social, environmental and economic policy. Advocacy around the pandemic is likely to follow a sequence:

1. Advocacy bearing witness to the impact of the pandemic, especially on vulnerable populations that are not getting sufficient attention from policy makers (eg those in shanty towns, prisons etc)

2. Advocacy for particular policy responses, such as debt relief, or safety nets for those in the informal economy

3. Advocacy to address the unintended negative consequences of the responses – for example the rise in gender-based violence during lockdown.

4. Advocacy to shape the priorities of subsequent recovery policies.

The tone and content of advocacy and campaigns will need to adapt to where we are in that sequence – business as usual is neither wise, nor feasible.

Watching the advocacy traffic on social media in the early days of the pandemic, I have been forced to rethink, or at least nuance, my previous exhortations to ‘never let a good crisis go to waste’.

Tone: At a time when the public is anxious, scared, and in need of comfort, I am startled by how much of the advocacy retains an angry, finger-wagging tone. All too often, the general message seems to be ‘we were right before; now because of the virus, we are even righter. Why aren’t you listening? You must be stupid and/or evil.’

I am not the only one. Writing in The Guardian, Martin Kettle observed:

Both left and right are currently guilty of acting as though nothing has really changed. Those on the left who believed before Covid-19 that Britain was collapsing under the weight of social inequality, a lack of Keynesian demand management or the folly of Brexit have looked at the crisis and concluded that, yes, the pandemic proves that they were right all along. Yet those on the right who believed beforehand that the economy was more reliably run in their hands, that borders needed to be rather more tightly controlled, and that nation states must make their own decisions feel equally vindicated.

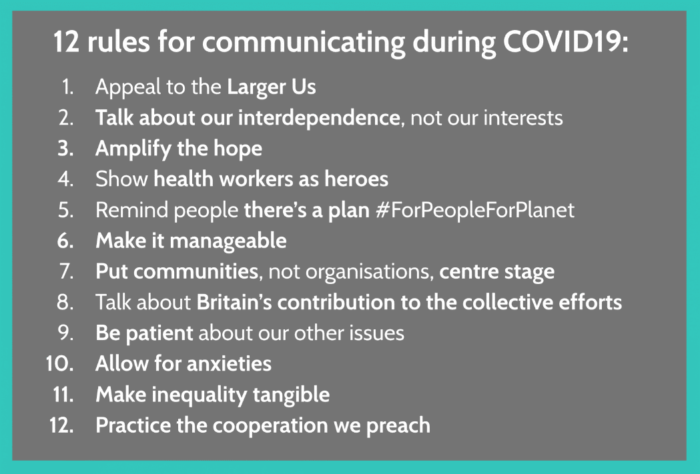

Getting righteous and angry seems a useful or effective approach right now. As Leila Billing writes in her post on feminist leadership and the crisis:

‘Holding feet to the fire, and espousing blistering critiques of our global economic, political and social systems will be paralysing and hope-quashing. As leaders, we must work collectively with others to put forward visions of a more just, equitable and inclusive future.’

A piece on Global Dashboard by Kirsty McNeill brilliantly captured the discussion on tone, summarized in these ’12 rules’:

Content: What might work better than knee-jerk ambulance-chasing? Some thoughts:

In the short term, be more prepared to welcome positive movement from the government or private sector. Monitor impact and feed back quickly and firmly on issues of exclusion and unintended consequences for vulnerable populations (for example on the likely upsurge in domestic violence during lockdown). Suggest positive alternatives or solutions. Use the crisis to build new relationships and earn trust for the future.

A nice local example comes from Myanmar, where senior local staff at the Centre for Good Governance spotted an opportunity to support the response to Covid-19. In the early days of the outbreak, they set up meetings with senior officials in the capital using their existing networks in government. At the request of a senior reform-minded official they hired an animator and rapidly produced an animation explaining Covid-19, the government’s response, and actions everyone in the community could take to contain the outbreak.

The animation was promptly adopted by the government after feedback from the national response committee and has now been distributed across government and community social media forums in Myanmar.

This on the face of it had little to do with CGG’s focus on local government reform other than supporting the government to provide accurate information, yet it cemented crucial relationships and political capital that can now be used to nudge the conversation on policy and system considerations during the response. It was also a step in the right direction for building public trust in the government’s ability to act decisively in the crisis, and to do so transparently.

What will emerge in the medium/long term is unpredictable, and activists will need to ‘dance with the system’ as it changes around them:

- Some existing advocacy priorities will become less salient – a real challenge to organizations where advocates become deeply identified with ‘their’ issue.

- Some advocacy priorities will become more relevant and powerful, provided they can be convincingly linked to the crisis (see the gender-based violence example, or the importance of the care economy).

- But new issues will also emerge, like the earlier discussion on space as a human right. After the Global Financial Crisis, smart advocates for economic justice realized that the new normal was fertile ground for reinventing the Tobin Tax as a global, remarkably effective campaign for a Financial Transactions Tax (aka Robin Hood Tax), which 12 years on is still being negotiated by 10 countries in the EU. Similar imagination and persistence will be required to make sure this latest crisis ‘does not go to waste’.

- New threats will also appear. In The Shock Doctrine, and her recent coverage of the pandemic, Naomi Klein has pointed out that what she terms ‘disaster capitalists’ are historically much more adept than progressives at seizing these windows of opportunity. Defensive strategies – stopping bad stuff from happening – are likely to become an important role for advocacy and campaigns as the crisis unfolds.

6. Final Thoughts

In a crisis, people often seek certainty. Those wielding crystal balls suddenly acquire an audience. Alas, I know they are a dangerous delusion, and have long since embraced ambiguity and uncertainty (sometimes to the irritation of my more gung-ho colleagues).

This paper has instead offered some precedents for the current moment, and ideas for how to navigate through the fog. That is the best I can do.

Stepping back from the detail of this paper, I am struck by the gulf between the discussion in governments such as the UK and US, and the response from the ground. At the level of national leadership, the moment feels more like World War One – a crisis that bequeaths a legacy of suspicion and non-cooperation for years or decades to come, sowing the seeds of future crises. But in the streets and communities, the upsurge in solidarity and compassion feels much more World War Two, a moment of courage and creativity, of new forms of human organization emerging to make the world a better place.

The question for advocates and campaigners then becomes how do we enable that World War Two spirit and commitment to find rapid and lasting political expression?

Karl Marx once wrote (in more gender-blind times) that ‘Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.’

If there is one message from this

paper it is that advocates and campaigners, fired up by what Martin Luther King

called ‘the fierce urgency of now’ must embrace, study and understand that

history in order to shape it. Because it is a history that is being written

right now, by all of us.

[1] A number of people have made helpful comments on this early draft. They include Esme Berkhout, Paul O’Brien, Talia Calnek-Sugin, Steve Commins, Philip Edge, Harriet Freeman, Irene Guijt, Molly Hall, Tom Kirk, Suying Lai, Mackenzie Schiff, Matthew Spencer. I thank them for their help, but any mistakes or misunderstandings are my sole responsibility.

Main Image: Critical Juncture – glass sculpture by Julia Malle