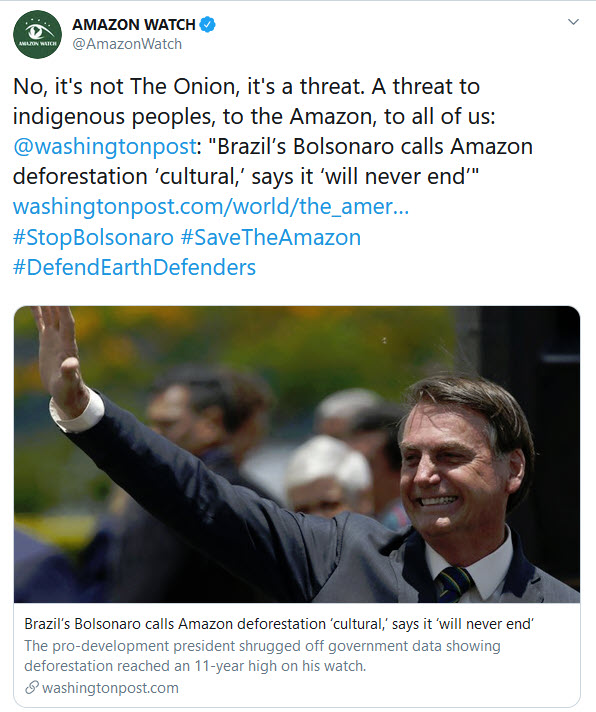

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro aroused global indignation in November when he affirmed: ‘Look, you’re not going to do away with deforestation, or the burning – its cultural’. But if he had said: ‘Look, you’re not going to do away with deforestation or the burning, because they are supported by federal laws passed before I became president’, he would have been closer to the truth.

He could have added: ‘and soon I’ll strengthen the law that created the conditions for deforestation’, because that’s prescisely what he did on 10 December 2019. On that day he signed a presidential decree that radicalized a law passed in 2017 which excused environmental crimes and the illegal land-grabbing of thousands of square kilometers of lands which until recently belonged to the federal government.

A number of recent studies reveal the close connection between deforestation and federal programs to sell federal lands to large property owners, at low prices, and with broad flexibility to regularize previous illegal occupations and associated environmental crimes.

The land-grabbers’ charter

After law 13.645/2017 was passed by congress (formalizing a presidential decree by previous president Michel Temer known as the ‘Land-grabbing Decree’), between August 2018 and July 2019 ‘35% of the deforestation in the Amazon took place on ‘non-designated areas without proof of registration’, according to a study by the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM – the Amazon Environmental Research Institute). ‘This is land-grabbing’, affirmed IPAM executive director André Guimarães, on 20 November 2019. ‘These forests are public, so that it is the patrimony of all Brazilians that is being illegally destroyed and winds up in the hands of a few’, he added.

Just a few months before, the eyes of the entire world had been fixed on Brazil while the Amazon burned at an unprecedented rate. A number of articles in the global press presented the Amazon as a ‘lawless’ place[1], where the lack of government oversight and disrespect for laws permit deforestation and fires.

In fact, however, it is the laws that create the conditions that are devastating the Amazon and the presidential decree Bolsonaro signed in December merely aggravates the already incendiary conditions. An informal but broad survey of the Brazilian and international media coverage of the Amazon fires found only a superficial recognition of the relationship between deforestation and existing laws that condone land-grabbing and previous environmental crimes.

‘In 2017, the Brazilian government revised the laws governing regularization of land and the new law jeopardises efforts to reduce the loss of Amazon forests’, affirmed Brenda Brito, of IMAZON, the Institute of People and the Environment of the Amazon in a July 2019 study. ‘The relationship between deforestation, land-grabbing, and violent conflicts over land issues, documented in previous studies, continues in the region. In 2017, Brazil had the highest number of murders of environmentalists and those who defend land rights, and 80% of the victims were in the Amazon region’, Brito added. A recently published report from Front Line Defenders and Human Rights Watch finds that the situation in 2019 remains at least as bad.

Laws that promote concentration of land ownership

So despite intense international media attention, it was not made clear that the unprecedented Amazon fires in 2019 were merely the most visible consequence of a process that had begun in the 1960s under the former military government. That process privatizes public lands, threatens indigenous lands and the world’s largest tropical forest, while facilitating an intense concentration of land.

For a few years beginning in 2009, laws establishing ‘The Legal Land Program’ encouraged the sale of federal lands to small property owners, some in collective agrarian reform settlements, and with rigid norms for forest protection and demarcation of indigenous lands[2]. But the laws and norms approved in the second decade of the century have weakened the protection of nature and small property owners, conferring amnesty for environmental crimes, and encouraging the transfer of public land to private and increasingly large landowners[3].

International media focused on Brazil because Amazon destruction seriously aggravates climate change. But for Brazil the social and economic consequences are also severe. The process of land regularization has cost the public coffers US$5–US$8 billion, because federal lands are sold at prices far below market value, according to Brito’s study.

Thus, the words of Brazil’s Environment Minister Ricardo Salles were profoundly misleading when he said, at the UN Climate Change Conference in Madrid on 9 December, that ‘the Amazon is the richest region in Brazil, with the worst Human Development Index – if we leave the people behind, it will be difficult to care for the environment.’ Misleading, because government policies help a few large property owners at the cost of the majority of ‘the people’ who, if they own any land at all, are small landholders.

‘The prospect of regularization intensifies processes of expropriation. Conflicts intensify, and the pressure to sell land to large landowners at ridiculously low prices forces many small farmers and extractivists to abandon the region. Local leaders have been killed or received death threats and had to leave the region’, according to Thereza Cristina Cardoso Menezes, a professor at the Federal Rural University at Rio de Janeiro, who worked in the New Social Cartography for the Amazon project from 2007 to 2014.

The situation worsened over the past year as the Bolsonaro government turns a blind eye to the violent invasion of dozens of unprotected indigenous lands. It is clear that for Minister Salles and the rural caucus in the Brazilian congress – which pressed for approval of the new Presidential decree on 10 December – that traditional, indigenous communities and the majority of small farmers can be ‘left behind’.

It’s not lawlessness, but the laws

So it is not ‘lawlessness’ in the Amazon that is responsible for deforestation. On the contrary, it is the law, specifically Brazil’s latest forest code, approved in 2012 by the government of President Dilma Rousseff, despite strong opposition from environmentalists in Brazil and throughout the world. The law marked the return to increased deforestation. The year it was approved had the lowest deforestation in recent decades. Since the law was passed, deforestation rose steadily.

Of course, various different factors contribute to increased forest destruction, such as variations in markets for cattle and soybeans, which are the principal products of the land obtained by forest clearance, as well as enforcement problems – many caused by recent dismantling of the environmental agencies. But the federal forest law of 2012 marked a sharp setback in protections in general, mainly because it offered amnesty for previous environmental crimes and weakened future protections for the forest.

The dismantling of controls over areas designated for permanent protection under the earlier forest code, approved in 1966, was aggravated even more in 2017 with the so-called ‘Land-grabbing Decree’, signed by then President Michel Temer, and which was soon turned into law by congress. The new law granted amnesty for illegal occupations of rural public lands between 2005 and 2011, and for forms of environmental destruction prohibited by the 1966 forest code. These benefits were extended to lands of up 2,500 hectares – one thousand hectares more per property than under the previous law.

Seven more years – of land-grabbing

But this was not enough for Bolsonaro.The decree he signed in December 2019 will prolong the retroactive period for amnesty of illegal activities until December 2018 (pardoning seven more years of land-grabbing and deforestation) and will eliminate inspection requirements, allowing ‘self-certification’ of compliance with environmental and property laws for holdings of up to 1,500 hectares.

The Amazon still has 70 million hectares of unregistered forest, all now subject to land-grabbing, ‘regularization’ and deforestation. These lands could become forest preserves or be allocated for other social uses, according to IMAZON. But it is obvious that Bolsonaro’s new land-grabbing decree will leave the second option improbable and will exacerbate the conditions that led to last year’s historic rise in deforestation.

The question

arises: when the world turns its attention to the fires that will certainly

flare again this year in the Amazon, will the focus be on the smoke, or on the

laws?

Banner image: An IBAMA environmental agency agent looks out over devastated rainforest within Jamanxim National Forest in Pará state Brazil. Under Bolonsaro’s executive decree MP 910, this illegal deforestation could be used as proof of “occupation” by land grabbers to lay claim to the public lands which they invaded. Image courtesy of IBAMA.

[1] ‘É um mundo quase sem leis’. El Pais Semanal 4/11/2019. and ‘Welcome to the lawless heart of the Brazilian Amazon.’ NYT 18/11/2019 p. A4

[2] During the government of President Dilma Rousseff, with supervision from the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ), the size of lots for agrarian reform increased from 1 to 2 fiscal modules. The size of a fiscal module is different in each municipality and varies from 5 and 110 hectares.

[3] The Report on Inspections of the Legal Land Program, issued by Brazil’s Federal Budget Court concluded in mid 2014 that of the 7,951 processes to issue land deeds, 5,607 referred to areas smaller than one fiscal modules (MF), totaling 174,577 ha; 2,056 processes were for plots of 1 to 4 MFs representing deeds for 263,429 ha and just 292 processes for plots larger than four MFs represented deeds for a total of 170,947 ha’. (Thereza Cristina Cardoso Menezes, da UFRRJ, forthcoming)

Jeffrey Hoff, once a NYC-based reporter, used a Fulbright Fellowship to study the role of the Brazilian press in the presidential impeachment scandal of the 1990s, the resulting investigation was subpoenaed by the attorney general and plagiarized by the rapporteur of the congressional investigative committee. He is now a community, environmental and urban policy activist in Florianópolis.