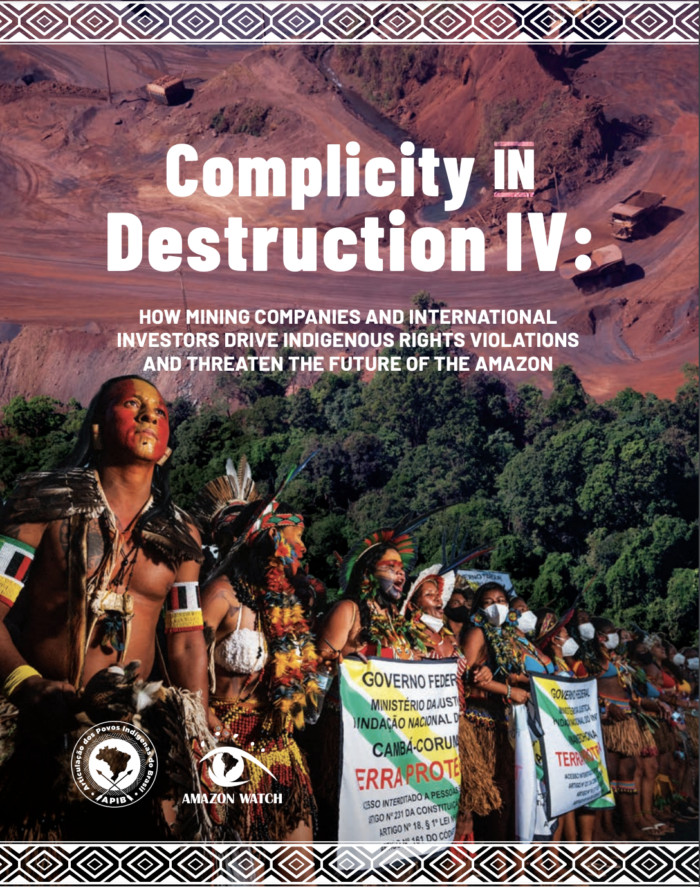

The latest report by APIB and Amazon Watch is the fourth in their Complicity in Destruction series covering continuing destructive mining practices in the Amazon and the impacts these have had on the lives of the indigenous populations of the forest.

It shows how companies have been applying for applications to mine in territory that has previously been demarcated for indigenous people under Brazil’s 1988 constitution.

Unsurprisingly, the ‘usual suspects’ corporations have been involved in financing this. These include venture capitalists such as Blackrock, Vanguard, and Capital Groups that have funnelled $54.1 billion dollars into various mining companies like Vale who have previously been accused of human rights violations and whose bad management led directly to the catastrophic tailings dam collapses at Mariana and Brumadinho.

APIB and Amazon Watch have discovered that out of the $54.1 billion dollars, funds of $14.8 billion dollars related to applications to mine on indigenous lands in Brazil. These are connected to American venture capitalists, Brazilian bank Bradesco, and Brazilian Pension funds. Almost 2,500 mining applications put forward by 570 companies and of those almost 10 per cent impinged on 5,700km2 of indigenous territories. What is more shocking is that, even though this is illegal, the ANM (Brazil’s National Mining Agency) submitted the applications without questioning them or cross-referencing to see if the proposed mines involved incursion into Indigenous territories.

The willingness of the private sector to exploit indigenous lands is laid bare throughout the report. This development could be attributed to President Jair Bolsonaro’s rhetoric surrounding neo-developmental projects in the Amazon, where levels of deforestation are at an all-time high (partially because of illegal mining), having increased by 62 per cent since he took office in January 2020.

Perhaps the private sector feels emboldened by his discourse which has led to a surge in illegal land grabs, and has created problems for Indigenous populations throughout the Amazon. For example, the Kayapo Indigenous territory has been invaded at gunpoint and two Yanomami children were killed when they were sucked into illegal mining equipment on a river barge.

Ecologies destroyed

The report highlights how the region’s ecology is dying as a result of these mining operations. The Kayapo, Yanomami, and Munduruku populations in the Amazon have all seen their local rivers become toxic with heavy metals such as mercury – which is used in mining operations. This has dangerous effects not just on humans (many of whom are living with dangerous levels of the chemical in their blood) but also the fauna, which in turn provide food for people who live along the rivers.

Mining operations which are killing the region’s rivers are also affecting the cultural practices of certain groups. The report mentions the Pataxó Hã-hã-hãe group who can no longer perform their ritualistic bathing in honour of Txopai (the Father of the Waters) because their river has perished. This, along with the violent illegal invasions of territories and the Covid-19 pandemic, is taking a toll on Indigenous people’s mental and physical health.

Signs of hope

Yet, in the midst of this dark situation, there have been signs of hope. Last year Brazil saw the largest Indigenous demonstrations in Brasilia against two bills going through Congress. The 191/2020 bill has the potential to destroy 16,000 hectares of indigenous land, and is in direct contradiction with article 169 of the ILO convention which states Indigenous peoples must be consulted when infrastructure projects are taking place in their territories. As Beth Simmons (2009) noted, Latin American states are ‘serial ratifiers’ when it comes to international conventions, and they don’t seem to mind breaking them when there is economic gain involved.

Bill 490/2007 changes the rules on how indigenous land would be demarcated, with a dangerous rule that if Indigenous people can’t prove they occupied a piece of land prior to the 1988 Brazilian Constitution, they can no longer apply for demarcation. Yet the Bolsonaro administration shows no hesitancy in promoting these bills.

APIB and Amazon Watch also draw attention to the mass of human rights violations taking place in the region, driven by these usual suspects, and to the ways in which indigenous people are resisting them.

The report frames APIB’s case of Genocide brought to the ICC as a ‘success’. It is a grim kind of success, however, that involves bringing the most serious criminal charge against a government. Rather we should see it as a necessary survival measure, erected to stem the slow tide of violence and genocide that has been plaguing Indigenous groups in the Amazon for centuries.

The report locates current violations within the longer history of mining and extraction in Brazil since the gold rush of the 17th century. Additionally, it describes how the last Brazilian military dictatorship (1964 – 1989) to which Bolsonaro often favourably alludes, was responsible for the construction of mining and extraction infrastructure in the Amazon.

The 2014 Brazilian Truth Commission (set up to investigate human rights abuses from 1946-1988) found that violence towards Brazil’s Indigenous populations became markedly worse following the passing of the AI-5 in 1968, which gave the head of state almost unlimited powers and institutionalised torture and repression. In that sense, this report only highlights the latest instalments of neo-colonial ventures, the violations being committed, and the struggles by Indigenous peoples for their territories and existence.

Simmons, Beth A. 2009. Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Main image: Daniel Beltrá/Greenpeace