On 27 February, the President of the Dominican Republic, Luis Abinader, announced new plans to build a high-tech border wall along 190 kilometres of the 391 kilometre Dominican-Haiti frontier. Symbolically stated before Congress on the 177th anniversary of Dominican Republic’s independence from Haiti, President Abinader declared that the ‘dividing line’ would put an end to the ‘serious illegal immigration problems, drug trafficking and the transit of stolen vehicles that we have suffered for years, and achieve the protection of our territorial integrity that we have sought since our independence’. Construction is slated to begin later this year, and the final result, expected in two years, is set to include double perimeter fencing in the most ‘conflictive’ zones and facial recognition technology, digital fingerprinting technology and infrared cameras. 60 kilometres of the fence has already been built.

Felipe Fortines, a spokesperson of reconoci.do, an anti-racist grassroots organisation which campaigns for the recognition and rights of Dominicans of Haitian descent, says it is ‘evident’ that the construction of the wall signifies racial discrimination against Haitians.

For as long as humanity has existed, we have always moved from one place to another, however many walls they build

Felipe Fortines – reconoci.do

The wall will also negatively impact Dominicans residing in the border towns, Felipe says, as they heavily depend on the trade and relationships they have with Haiti. It will interrupt the symbiotic relationship that Haitians and Dominicans living on either side of the border have developed over a lengthy period of time, worsening the situation for both.

‘For as long as humanity has existed, we have always moved from one place to another, however many walls they build…it seems paradoxical that in an area like the border, practically the most destitute area of the country which is lacking in so many things, those resources that they are going to invest in a wall could have been invested in helping the people to grow, to develop, to empower the area.’

The Haitian present: turbulent times

The Dominican president’s announcement comes at a particularly volatile and vulnerable time in Haiti, as protesters have been taking to the streets of the capital of Port-au-Prince since early February to denounce President Jovenal Moise’s government which they accuse of trying to establish a dictatorship. Two Dominican brothers and their Haitian interpreter were recently kidnapped in Port-au-Prince whilst a mass-escape from a Haitian prison resulted in 25 people dead.

The plan for the new wall reinforces the stark differences between the two nations which share the island of Hispaniola. On the one hand, Creole-and-French-speaking Haiti on the Western side of the island has been the long-suffering victim of colonialism, neo-colonialism and imperialism, rendering it the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere. And on the other hand, the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic is the fastest growing economy in Latin America and the Caribbean owing to the expansion of construction, tourism, and free-trade zones.

As a consequence, tens of thousands of Haitians have been relying on informal employment in the agriculture, construction and domestic service industries in their neighbouring country as a means of survival. These jobs are typically poorly paid, with little to no security or rights, and off-record, as few Haitians possess identity papers. These issues have been exacerbated by the pandemic, as a Human Rights Watch report highlighted how the Dominican Republic suspended temporary legal status for more than 150,000 Haitian workers in response to Covid-19.

According to estimates, between 650,000 and 1 million Haitian immigrants were resident in the Dominican Republic as of 2018, along with their children born in the country, meaning that they make up about 5% of the total population. Inevitably, the construction of a border fence will have far-reaching and detrimental consequences for Haitians and Haitian migrants in the Dominican Republic.

Antihaitianismo: a Dominican story

The establishment of a border fence between Haiti and the Dominican Republic can be read as a continuation of ‘antihaitianismo’: a specific form of anti-Blackness against Haitians that has been a central tenet of the Dominican state for decades. In 2013, antihaitianismo surfaced in a ruling of the Dominican constitutional court, based on a retroactive reinterpretation of an existing law, to erase the birthright citizenship of Dominicans of Haitian descent. It decreed that those born in the Dominican Republic between 1929 and 2010 were entitled to citizenship – but that those born to undocumented migrants were not. This amendment resulted in the Dominican Republic deporting an estimated 70,000 to 80,000 people of Haitian descent in the following three years, deepening the state of ‘institutionalized terror’.

The origins of Dominican antihaitianismo are intimately tied to the racial history of the island and can be traced back to the beginning of the colonial period. The Spanish Crown infamously colonized Hispaniola in 1492 and swiftly set into motion the importation of Black slaves who they sent to work on the sugar plantations. These were the ‘first Blacks in the Americas’, whose presence forged the conceptual link between slavery and race. However, the world market for sugar collapsed and disease afflicted the enslaved population, effectively ending the plantation system and diminishing the significance of slavery. Thus, strict racial hierarchies dissolved, giving rise to a racially-mixed mulatto population that emerged in the 17th century. As colonists’ use of the term ‘Black’ was confined to those still enslaved or engaged in subversion against colonial rule, freed Blacks and mulattos could ‘step outside the racial circumscription of their blackness in configuring their identities’.

It was during this century, in 1697, that Spain relinquished the Western third of the island to France, which France renamed as Saint-Domingue. Saint-Domingue heavily relied on the practice of slavery to produce and export sugar as well as coffee, cacao, indigo, and cotton, quickly making it France’s most lucrative New World asset, known as the ‘Pearl of the Antilles’. Nevertheless, existing resentment amongst the enslaved population intensified, culminating in the Haitian revolution in which the self-liberated slaves overthrew French colonial rule in 1804, seizing independence in the only successful slave revolt in human history.

Capitalizing on their recent victory, Haitian troops invaded the Eastern part of Hispaniola inaugurating an occupation, which lasted 22 years, until Dominicans overthrew Haitian rule in the War of Independence in 1844. Newly independent, the Dominican state constructed a racialised national identity grounded in the logics of antihaitianismo in order to differentiate themselves from Haiti. Henceforth Dominicans were cast as the light-skin mulatto race of exclusively Spanish and indigenous Taíno ancestry in opposition to Haitians, who were framed as definitively Black and African due to their darker complexion.

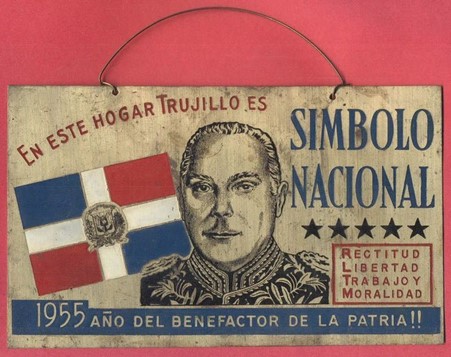

Dictator Rafael Trujillo, who brutally ruled the country from 1930–1961, embedded this racialised ideology in the Dominican psyche by forcefully obliterating African heritage whilst simultaneously constructing an imagined indigenous past and institutionalizing antihaitiansimo. As such, Trujillo’s regime criminalised African cultural expression and authorized the mass-deportation of Haitians along the border in an ethnic-cleansing campaign. Most notably, Trujillo orchestrated the killing of up to 30,000 Haitians on the frontier in the genocide known as the ‘Parsely Massacre’ in 1937.

Along the border where the Dominican state murdered thousands of Haitians, they will now build a wall, continuing the anti-Black ideology of antihaitianismo.

Building walls rather than bridges?

It is clear that President Luis Abinader’s planned wall is part of an overt political strategy to strengthen the criminalization and ‘Othering’ of Haitians; reinforce the divide between Haiti and the Dominican Republic; and garner Dominican public support for present and future anti-Haitian state actions. In building a wall, the Dominican government locates itself alongside oppressive right-wing administrations in other countries which have built and advocated for border walls, such as Donald Trump’s in the USA, a comparison that Felipe assured me has not gone unmissed in the Dominican Republic, and Ariel Sharon’s in Israel.

It does not have to be this way. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests around the world last year, the abolitionist movement, which works to imagine and create an alternate world that does not depend on punitive and harmful measures, experienced a global resurgence. And so, in line with envisioning a different way of doing and a different way of being, Felipe captured the zeitgeist by asserting, ‘I think that what the State should do is, rather, before building a wall, build bridges of understanding, growth and development. That, yes, is missing.’