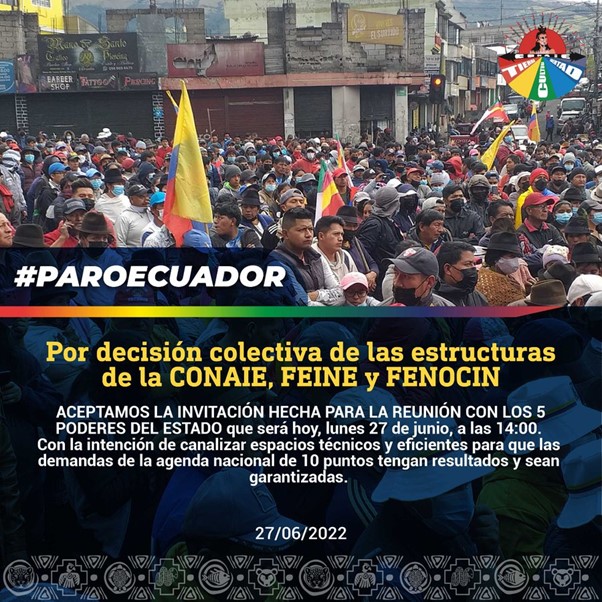

On 30 June, concessions by both government and protestors brought to an end three weeks of acute crisis, precipitated by sharp rises in food and fuel prices and dramatic shortages. The protests were led by Leonidas Iza Salazar, President of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) in a coalition with the National Confederation of Peasant, Indigenous and Black Organizations (Fenocin), and the Council of Indigenous Evangelical Peoples and Organizations (Feine).

Students, trade unionists and opposition party UNES joined in the demonstrations. Calm has returned, for the moment, but simmering discontents with the Lasso government and its penchant for authoritarian response suggest that the truce may be short-lived.

On Thursday, representatives of the Catholic Church mediated a dialogue through which an agreement was signed between Leonidas Iza and Minister of Government and Policy Management, Francisco Jímenez. The agreement was also signed by negotiator Monsignor Luis Cabrera, head of the Episcopal Conference in Ecuador. The accord foresees a reduction in the prices of both gasoline/petrol and diesel, sets limits to the expansion of oil exploration areas, and prohibits mining in protected areas, national parks and around water sources.

In an exclusive interview with the Latin America Bureau on 30 June, Kichwa environmental activist Leo Cerda, from Serena, Napo province, expressed the protestors’ jubilation at the climbdown of the government.

‘It has been a long 18-day journey’, he said. ‘Lasso’s government is in a weak political state. The indigenous people made precise demands made from their personal experience, from the reality they were facing every day. [There must be] no more extraction. Reductions in fuel prices will be targeted subsidies in the long run. As a movement, we know that targeted subsidies are not the answer, but people cannot live with the daily inflation that rising prices inflict on everyday production, including transportation. More than 43.3 per cent of indigenous people in Ecuador live in extreme poverty, earning US$48.24 on average monthly, while indigenous people are the ones sustaining Ecuador’s food production…More than 70 per cent of Ecuadoran families cannot afford to buy the [officially defined] basic basket of food.’

Later, he warned: ‘We have to wait for the final resolution. Article 151 [a government decree issued on 5 August 2021 allowing for expansion of mining] has not been completely repealed. We do not want mining on indigenous territory. Artisanal mining will be controlled. The government has three months to fulfil its promises, and if it does not do so, then there will be another mobilization.’

Behind the action and fury lie deep-seated problems of inequality, the poverty and marginalisation of indigenous communities and the escalating threat to life and the environment posed by the expansion of mining, oil and gas extraction.

On 26 June, as the tide of protest reached the centre of government, Ecuadorian president Guillermo Lasso narrowly survived a vote of no-confidence in the National Assembly, when the opposition led by the Correista Union of Hope (UNES) party failed to secure a majority to secure the President’s resignation.

From May 2021, Guillermo Lasso’s minority Creating Opportunities Party (CREO) has led a centre-right government in coalition with indigenist party Pachakutik, whose representative Guadalupe Llori was initially appointed as leader of the National Assembly. Splits soon developed within Pachakutik, as dissenters decided that they could not support neoliberal policies introduced by Lasso. Llori had to resign as leader of the Assembly within a year, and these manoeuvres contributed to the administration’s deep unpopularity among all sectors.

The wave of protests

The protests that began on 13 June brought the capital Quito to a halt, with road blocks leading to shortages of food in cities such as Cuenca. Military trucks and tyres were set on fire. Eight people were reported killed, and thousands arrested, with 160 people remaining in custody after the peace agreement was signed.

On 20 June, leaders of CONAIE, Feine and Fenocin had gathered at the Casa de la Cultura, founded in 1944, which has become a centre of indigenous resistance in Quito. Presiding over the meeting was CONAIE vice-president, Zenaida Yasacama, in the absence of CONAIE president Leonidas Iza, who was in court in Latacunga, charged with sabotaging public services. He had been held in detention by the armed forces for several hours on 14 June.

The indigenous federations’ call for the resignation of President Lasso, accompanied by chants of ‘Fuera, Lasso, Fuera’, was to be voted on at the local level, before being taken forward into the National Assembly.

The protestors delivered a list of 10 demands to the government:

- A reduction and freeze in the price of fuel. Subsidies for farmers, peasants, transport workers and fishermen.

- Financial support for more than four million families, with a moratorium on debt service payments and a reduction in interest rates. A halt to repossession of houses and cars for failure to keep up with monthly payments.

- Guaranteed prices for agricultural production of small and medium-sized farms: milk, rice, bananas, onions, fertilisers, potatoes, maize and tomatoes.

- Public investment in jobs to provide greater job security for the working class.

- A halt in the expansion of the extractive frontier to protect territory, water sources and ecosystems, with compensation for environmental damage.

- Adherence to the 21 collective indigenous rights, including bilingual education, indigenous justice, free prior and informed consent for development projects, rights to organisation and self-determination.

- An end to privatisation of public services in strategic sectors such as the Banco del Pacifico, hydro-electric dams, Social Security (IESS), National Telecommunications Corporation (CNT), roads and health care.

- Control of prices and of speculation in basic goods, which has led to abuses by intermediaries, raising prices in supermarkets.

- Resupply of public hospitals that are short of medicine and personnel. A guarantee for young people to access higher education, and improvement of infrastructure of schools, colleges and universities.

- Security, protection and effective public measures to halt the wave of violence, contract killings, delinquency, narcotrafficking, kidnapping and organised crime disrupting the country.

Conciliation and crackdown

Initially, the President issued a statement in which he addressed each of the demands in turn, appearing to make concessions on most of the points, though initially there was no commitment to halt all new oil exploration. Lasso announced a plan to restore 1,107 areas damaged by Texaco-Chevron in Sucumbíos and Orellana provinces, and other initiatives to restore areas damaged by mining. There was to be a 50 per cent subsidy on fertiliser and provision of seeds and other inputs for farmers, guaranteed prices for agricultural products, and a US$5 increase in the monthly conditional cash payments, the Bono de Desarrollo Humano (BDH) for disadvantaged families.

On 24 June, however, President Lasso declared that the national police and the armed forces would be deployed to crush the uprising and authorized to use live ammunition. He called on the indigenous and peasant demonstrators to return to their homes, denouncing the CONAIE president for conspiring to bring down the government.

The Casa de la Cultura was raided and occupied by the police on 25 June, who declared that they were looking for weapons and explosives. It was then re-taken by the protestors.

The Lasso government called in support from the governments of Brazil and Colombia, who sent planes to deliver supplies to areas where roads had been blocked by demonstrators.

Manoeuvres in the National Assembly

The 26 June vote in the National Assembly was tabled at the request of UNES, who were hoping to invoke Article 130.2, of the Constitution, by which the President can be dismissed if 92 National Assembly Members support the motion. The governing BAN-CREO, the Social Christian Party (PSC), the Democratic Left and, initially, the indigenous party, Pachakutik, the political arm of CONAIE, refused to endorse the bill.

The Pachakutik alliance coordinator, Salvador Quishpe, explained that Pachakutik would not allow the return of Correismo, having felt betrayed by Rafael Correa, whose candidacy for the presidency they initially supported in 2006.

In the absence of the required 92 votes to oust him, Lasso’s hold on the presidency appeared to be secured in the short term.

Quishpe, however, changed his mind within 24 hours, while other members of Pachakutik announced that they would support the motion. In the end, there were 77 votes in favour of dismissing the president, including those of Pachakutik and Pachakutik Rebelde, and 55 in support of Lasso, including one member of Pachakutik.

However, the margin was not sufficient to remove Lasso. There remains the possibility for the Assembly to invoke Article 148 of the Constitution, which would dissolve parliament, triggering new presidential and parliamentary elections within a week.

The position of the indigenous peoples

Leo Cerda, Facebook post, 27 June: ‘We will continue to resist state violence, contamination, hunger, and politicians who attack us and the Rights of Nature!

We in the NAPO communities condemn the violence against the national strike demonstrators, and we condemn President Guillermo Lassos increasing use of force against us.

The social movements, Indigenous peoples and nationalities of Napo have been demanding for two years an immediate halt to the legal and illegal mining in our province, because these activities are an assault on our communities, on our rivers and our ecosystems.

As the authorities have disregarded all of our demands, we have taken to the streets to reclaim our right to live with dignity in an uncontaminated environment.’

In an interview recorded on 3 March, Leo Cerda explained the conflict in Napo and the threat of increased prospecting and mining of gold:

Wealth and inequality in Ecuador in the age of the commodity consensus

Ecuador is rich in natural resources, with mineral fuels, including oil, accounting for 26 per cent of exports, fish and crustaceans 20 per cent, fruits 20 per cent, live trees, plants and cut flowers 4 per cent. Oil exports generate US$5 billion per year, bananas and crustaceans (mainly shrimp/prawns) nearly US$4 billion per year each. Ecuador is the world’s largest exporter of bananas, and has become the ninth largest exporter of gold ore. But while indigenous people sustain the country’s food production for home consumption, according to Leo Cerda, 43.3 per cent live in extreme poverty earning less than US$50 dollars per month, with 70 of families in the country unable to buy the basic, officially defined minimum basket of food.

It is clear that much of the wealth generated has remained in the hands of the few. Inequality decreased in the period of the first Correa administration up until 2011, but poverty and extreme poverty began to increase after a drop in oil prices in 2014.

It was estimated by the NGO Stand.org that US$10 billion dollars’ worth of oil had been exported from Ecuador in the last decade, yet 50 per cent of the country’s children – half them indigenous — are malnourished. Agricultural prices within the country have remained low, making it difficult for farmers to make a living. At a time when global commodity prices have been rising, particularly with the price of oil rising above US$100 per barrel in 2022, questions have to be asked as to who in Ecuador has been reaping the benefits from commodity exports.

Follow the money: corruption and crime

One of the legacies of Ecuador’s colonial past has been dependence on primary commodities and export markets in the Americas and Europe, and, more recently, to China. Particularly in the oil sector, diversion of funds and avoidance of tax liabilities have been commonplace, as well as benefits derived from hidden payments to government officials in return for contracts, in the building sector and in infrastructure, finding their way to tax havens. All of this, of course, reduces government capacity to deliver services to citizens and exacerbates poverty.

The Covid pandemic, which took a heavy toll on Ecuador, afforded lucrative new opportunities for corruption in the health sector, with secret payments made in government procurement for PPE, equipment and medicines.

Already under the Correa administration, secret payments to government officials, particularly in the oil sector, had been diverted to Florida, Panama, and a number of tax havens in the Caribbean and Europe, as revealed by the Panama and Pandora Papers of 2016 and 2021. President Lasso himself, former CEO of the Bank of Guayaquil, had legally transferred his accounts in Panama into trusts in South Dakota, USA, for the benefit of family members, prior to assuming the Presidency in 2020.

Alongside the diversion of funds from the legal, regular, sectors of the economy have been the mounting profits from the illegal commodity economy. This includes trade in illegal timber, the trafficking of animals and the export of narcotics. The expansion of this last sector, in particular, has fuelled a dramatic rise in violent crime in the coastal cities of Ecuador, above all in the main port of Guayaquil, where there have been daily murders. Colombian and Mexican cartels have infiltrated the country, using Ecuadorian ports to export cocaine produced in Colombia.

The number of murders in the first two months of 2022 was the same as for the previous 12 years, according to the police, with 10 deaths per 100 inhabitants in both Esmeraldas and Sucumbíos provinces, along the Colombian border. In Esmeraldas, there were 67 violent murders in January and February 2022, with 36 of those believed to be contract killings of young men with an average age of 28. The number of murders in Esmeraldas quadrupled in one year.

Drug trafficking is accompanied by extortion, sale of stolen goods and smuggling. Researchers have concluded that in four towns, Durán, in Guayas; Zaruma, in El Oro; San Lorenzo in Esmeraldas; and in Lago Agrio, in Sucumbíos province, the criminal gangs have control of the governance of the towns, having terrorised the civilian population into silence.

Drugs from Esmeraldas, marijuana and ‘creepy’ marijuana, are sold on the streets of Guayaquil, the country´s main port, south of Esmeraldas, sometimes by children as young as 10.

Prison doesn’t work

The government has continued to seize shipments of narcotics but appears to be losing control. Prison is no remedy. Contract killings are on the increase, with hundreds of prison inmates losing their lives in prison riots. There have been around 400 deaths in prisons since February 2021, after years of government neglect and a conspicuous lack of training of guards.

In one such incident on 29 September 2021, 118 prisoners died and 79 were injured at the Litoral prison of Guayaquil during a battle between two gangs, the Los Lobos and Los Choneros, for overall control of the institution. Corruption surrounding the prisons is rife, with criminal groups extorting payments from families of inmates to ensure provision of food.

United Nations Special Rapporteurs on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary executions and on Torture made a joint statement in December 2021, saying they were ‘appalled and gravely concerned’ about the deaths and injuries, demanding urgent measures to prevent more deaths, citing international law on the treatment of prisoners.

It is clear that the Lasso government continues to face crises on all fronts, not least as a result of past neoliberal policies that involved a reduction in subsidies and services, failure to invest in improving conditions for prisoners, and failure to address the needs of working class and indigenous communities. Extreme levels of poverty have increased pressure on indigenous communities in rural areas, whose lives and livelihoods have been adversely impacted by illegal logging and mining, and by oil contamination. The failure to address poverty has also impacted upon the inhabitants of urban areas, particularly in coastal cities and frontier towns where foreign cartels have taken power, generating fear and insecurity.

While the government of President Guillermo Lasso has restored order for the moment through granting concessions to the protestors, his hold on office remains precarious while he presides over a minority government. In the meantime, Indigenous leader Leonidas Iza has consolidated support through the successful collaboration among CONAIE, Fenocin, and Feine that has brought about reversals in government policy. Through building upon this initial broad-based working-class and indigenous alliance, the CONAIE president hopes to create strong political force to bring about a transformation of the Ecuadorian state and economy.

Main image: from CONAIE web-post.

Sources include:

Becker, Marc, “In Ecuador, Indigenous-led National Strike Intensifies.”, NACLA.

Reyes, Xavier “Leonidas Iza: comunismo indoamericano o barbarie; la disyuntiva del dirigente indígena que puso a la Conaie más lejos de los “abuelos” y más cerca del marxismo.” El Universo, 17 June 2022.

Linda Etchart is a lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Kingston, Surrey, UK. She is the author of Global Governance of the Environment, Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature: Extractive industries in the Ecuadorian Amazon, London: Palgrave Macmillan 2022.