This article is based on research by Pedro Cabezas and John Cavanagh for the Institute for Policy Studies.

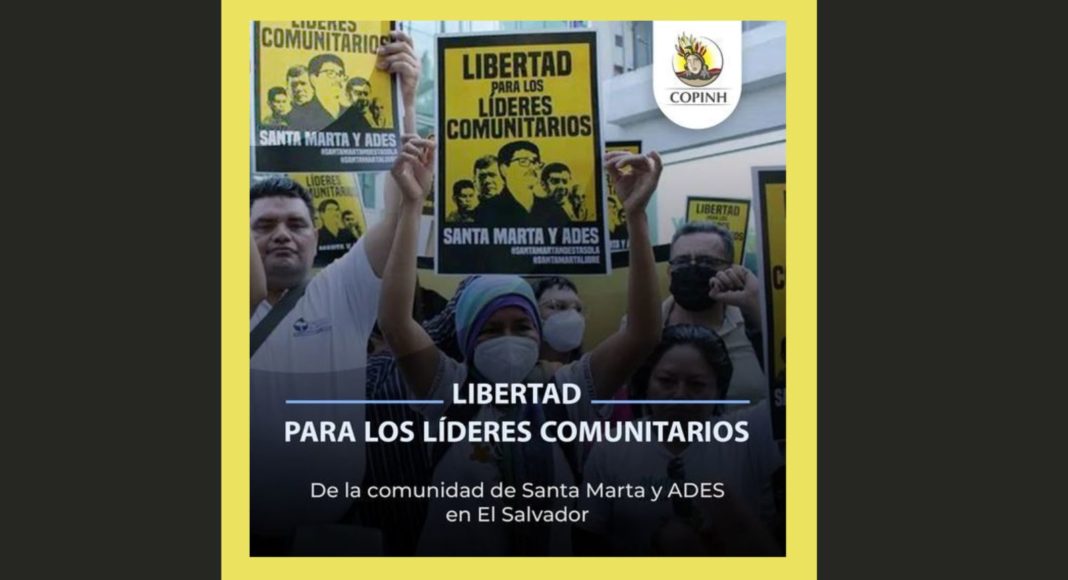

On January 11, at the order of the Salvadoran Attorney General, police arrested five prominent Water Defenders in northern El Salvador: Miguel Ángel Gámez, Alejandro Laínez García, Pedro Antonio Rivas Laínez, leaders of the community of Santa Marta, Cabañas; and Teodoro Antonio Pacheco, the director and Saúl Agustín Rivas Ortega, lawyer of ADES, the Association for Social and Economic Development of Santa Marta.

The Santa Marta Five, with others, had led the historic and successful campaign that convinced the Salvadoran legislature to unanimously pass a ban on metals mining in 2017 to save the nation’s rivers. The coalition they helped to build was in 2009 awarded the Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award.

Undue process

The five are accused by El Salvador’s Attorney General of being former FMLN guerrilla fighters and of having kidnapped, tortured and murdered María Inés Álvarez García Leiva on 22 August 1989, during the brutal civil war in El Salvador. The case was initiated in April 2022 by the daughter of the victim. Yet the body of the victim was never found, and some or all of the accused have alibis which place them elsewhere at the time.

The men are being held temporarily at a judicial detention centre in Soyapango with many restrictions: they are being held in isolation, families have not been allowed visits, the lawyers can only see them for five minutes, and they are only allowed medication with a doctor’s prescription which they cannot get as they have no access to health care providers. This is particularly harsh for Antonio who takes natural supplements prescribed by naturopaths, but officials at the detention centre do not acknowledge naturopathic medicine.

The group’s lawyers are appealing for them to be released on bail, but have yet to succeed in getting a hearing scheduled.

During the first hearing on 19 January, defence lawyers asked for the case to be dismissed, but the judge ruled that it should proceed and the defendants be remanded in custody for six months, while the prosecution gathers evidence. Previous experience suggest that this phase could last 18 months or more before being brought to trial. The Attorney General has also applied for the case to be heard in camera, with the public and reporters excluded and the defence prohibited from comment.

The defence believes that the case is politically motivated and that the government will use every stratagem to keep the men locked up for as long as possible. In many ways their experiences parallel those of the Guapinol Defenders in Honduras and the Bernardo Caal case in Guatemala.

The prosecution is relying on human rights law and is attempting to frame the charges as a war crime. The case will be heard by a tribunal that set up specifically to deal with war crimes. This is a tribunal that has so far failed to mount a successful prosecution against a single member of the Salvadorean military, despite the fact that, according to the UN, more than 85 per cent of the crimes committed during the civil war period were committed by armed forces personnel. The president has also refused to open military archives even though he has been ordered by the courts to do so.

Meanwhile in Santa Marta, community members cite dozens of cases that have been started by victims of raids conducted by the military during the war, but which have made little if any progress. They have documented three particular cases of massacres of civilians: The Lempa Massacre (43 civilians assassinated and 189 dissapeared); Los Planes Massacre (27 civilians assassinated); and Santa Cruz Massacre (about over 100 people massacred).

The link to mining

Today, thanks in part to its ill-advised embrace of Bitcoin, the Salvadoran government is under enormous pressure to find new revenues. It is reportedly considering overturning the mining ban, and allowing environmentally destructive projects to go ahead. Environmental and human rights organizations in El Salvador have stated that the arrests are politically motivated as they seek to silence these Water Defenders and to demobilize community opposition at this critical moment.

President Bukele has not himself expressed any public views on mining but antimining activists of the National Roundtable Against Mining have expressed public concerns that the government is taking steps to attract mining investment by reversing the ban implemented in 2017.

According to John Cavanagh, writing in Inequality.org and The Institute for Policy Studies, the present case against the five water defenders is targeting the head of one of the most effective anti-mining campaigning organizations, ADES, which in the early 2000s played a leading role in building up a National Roundtable on Metals Mining. Their efforts won over a strong majority of the public and rallied the Catholic Church, farmers, small businesses, and labour and environmental groups to oppose mining.

For more than 30 years, the focus of mining companies in Cabañas has been the gold deposits near the Lempa River, the water source for more than half of El Salvador’s 6.2 million people. These attracted Canadian company Pacific Rim.

In 2009, Pacific Rim (later bought by Australia-based OceanaGold) filed a lawsuit against the government of El Salvador, eventually demanding $250 million in compensation for the loss of profits they’d expected to make from their mining project there. For the cash-strapped country, that was the equivalent of 40 per cent of the national public health budget.

The behaviour of mining companies in Latin America, the resistance they encounter from local communities, their attempts to co-opt community leaders, reliance on violence and intimidation when thwarted, and habit of suing governments that impose restrictions -– are documented in LAB’s new book:

The Heart of Our Earth – community resistance to mining in Latin America by Tom Gatehouse — which will be published on 24 March 2023. You can order copies here.

This legal blackmail occurred amidst an explosion of violence against anti-mining activists, including the murder of Pacheco’s fellow campaign leader Marcelo Rivera. Several people have been convicted of Rivera’s killing, but to this day the ‘intellectual authors’ have never been held accountable.

Pacheco also faced personal death threats. In the wake of Rivera’s assassination, one note read: ‘The hour has come…[Pacheco] for the bomb in your own house and of your pals, now is the hour you pay for what you did…[You are] the next like Marcelo Rivera.’

After the ban on metal mining was introduced in 2017, activist organizations of the National Roundtable Against Mining focused their energies on demanding that different government institutions move to implement regulations that ensure the following:

- Proper closures of 15 abandoned mining sites that currently pose safety risks for the population and/or are currently contaminating local watersheds.

- That the government implements alternative economic development programs to help artisanal miners move to more sustainable economic activities. The Mining Prohibition Law gave the government two years to do this, but so far, no remedial measures have been taken.

- To investigate the murders of four antimining activist assassinated during the conflict in 2009.

- To ensure that the government takes steps to monitor potential contamination that could arise from the over 42 exploration sites that have been identified in the Honduran and Guatemalan borders which affect Salvadorean watersheds.

Then the company struck back. In 2009, Pacific Rim (a Canadian firm later bought by Australia-based OceanaGold) filed a lawsuit against the government of El Salvador, eventually demanding $250 million in compensation for the loss of profits they’d expected to make from their mining project there. For the cash-strapped country, that was the equivalent of 40 percent of the national public health budget.

This legal blackmail occurred amidst an explosion of violence against anti-mining activists, including the murder of Pacheco’s fellow campaign leader Marcelo Rivera. Several people have been convicted of Rivera’s killing, but to this day the “intellectual authors” have never been held accountable.

Pacheco also faced personal death threats. In the wake of Rivera’s assassination, one note read: “The hour has come…[Pacheco] for the bomb in your own house and of your pals, now is the hour you pay for what you did…[You are] the next like Marcelo Rivera.”

Mining is back

The Bukele government, however, appears to be taking measures for the eventual resumption of mineral exploration and extraction.

In August 2021 El Salvador joined the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, a Canadian based NGO receiving millions of dollar in support from the Canadian Government, whose mandate is to promote ‘sustainable’ mining practices around the world. In December 2021, representatives of the IGF conducted a feasibility study on Sustainable Mining of behalf of the government of El Salvador. Activists stated that those leading the study were posing misleading questions and giving different justifications for their study, depending on who they were interviewing.

In October 2021 the government created the Directorate of Hydrocarbons, Energy and Mines. Environmentalists took this inclusion of ‘mines’ as a clear sign of intent to bring mining back.

In early 2022, Antonio Pacheco, one of the detainees and director of ADES in Cabañas, told several different socials organizations that there were suspicious individuals approaching farmers in areas of mining interest and offering multi-year leases for large quantities of land with the option to buy.

Pacheco´s testimony has been corroborated by other local leaders and members of municipal councils who report approaches by outsiders who are offering funding for social programs with the municipalities.

More recently at least two mayors in mining region of Cabañas have confirmed they have had meetings the president of PROESA (the exports and investment office of the Salvadorean government) and have been told that the re-introduction of mining is coming, apparently with new technology claimed not to be damaging to the environment.

El Salvador is currently negotiating a free trade agreement with China, there are unconfirmed testimonies that mining is on the negotiating table. China has become the main source of foreign aid for the government of Nayib Bukele while it has cooled relations with the US and European countries. China has also offered to buy country´s foreign debt.

OceanaGold, the company that sued El Salvador for US $250 million in 2009, closed operations after it lost the case in 2016, but there is evidence that the company is trying to reinstate operations in El Salvador.

Financial reports published by the company in 2022 still show a connection to Pacific Rim and its subsidiaries in El Salvador. Two mining companies with company links to OceanaGold (Bienestar and Exploraciones El Dorado) remain registered and active. In fact, the capital of Exploraciones El Dorado has increased over the years.