Nick Caistor writes: The Nicaraguan poet and Catholic priest Father Ernesto Cardenal died at the age of 95 in Managua on Sunday 1 March, 2020. LAB thought it would be a fitting tribute to publish the lengthy interview I had with him in Managua a decade ago. Since then, Cardenal remained active as a poet and sculptor despite his declining health. He received more international recognition for his work, winning the Reina Sofia award for Ibero-American poetry in 2012, and being awarded the Légion d’Honneur by the French state a year later. He continued to live in Managua, despite his tense relationship with the Ortega regime, and was a vocal opponent of government repression of the widespread protests in 2018. What gave him the greatest satisfaction in his final years were the moves that Pope Francis made, first to absolve him from ‘canonical censure’ in2014, and then to lift the ban on him preaching, a year before he died. He is to be buried in his beloved community on the island of Solentiname on Saturday 7 March.

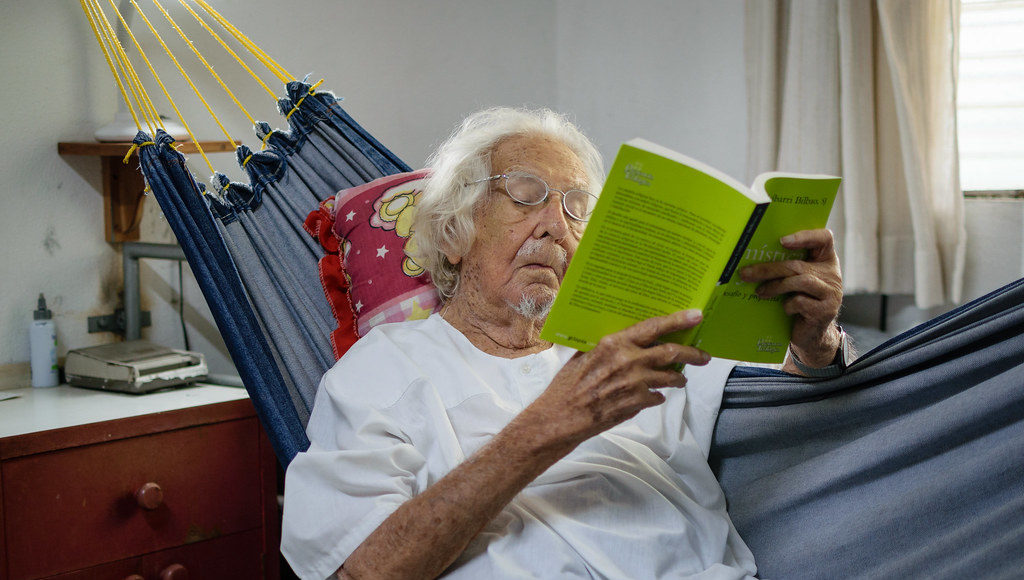

With his flowing white hair and snowy-white beard, at the age of eighty-four Father Ernesto Cardenal looks every inch an Old Testament prophet. And like many of the biblical patriarchs, his faith has led him into many battles.

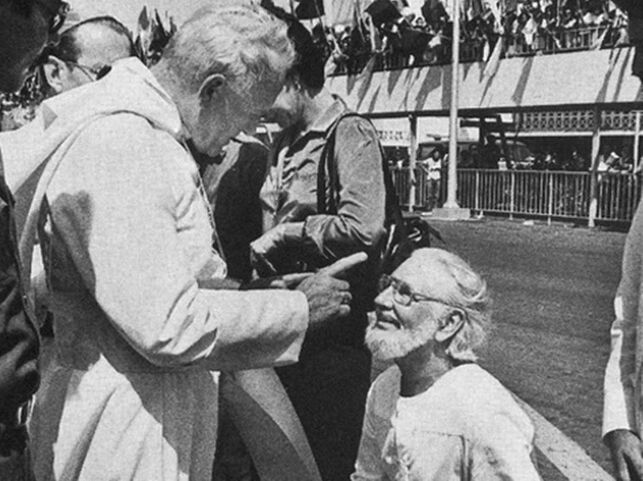

It was in 1983 that the image of him being publicly rebuked by Pope John Paul II on the tarmac of Managua airport in Nicaragua was flashed around the world. The Pope was taking him to task for being a minister in the revolutionary Sandinista government, and soon afterwards this was followed by a ban on Father Cardenal administering the sacraments.

This ban is still in place, although as he sits in a rocking chair in the airy living-room of his quiet house in Managua, where the only sounds come from the birds in his large, exuberant garden, Father Cardenal does not seem too concerned. He even says that he has heard the pope subsequently regretted his angry gesture, and that ‘during his final illness, when he saw the scene again on television, the Pope told his press secretary that he regretted it, because one priest should never publicly criticise another’.

Father Cardenal has always insisted that he has had a triple vocation as a ‘poet, a revolutionary, and a priest’, and sees no contradiction in this: ‘I have never felt that the love of God is an end in itself, but it means we have to put God’s love for us into practice, to show we love our fellowmen. In that sense, believing or not believing is not as important as putting that love into practice.’

Todo hombre es poeta. Olvidan hacer versos porque se dedican a hacer otras cosas, hacer dinero, por ejemplo.

‘Everyone is a poet. They forget to write verse because they spend their time on other things… making money, for example.’ -from Vida Perdida, Memorias I.1

As a young man, it was the poetic impulse which came first. In the 1950s, he wrote love poetry in his native city of Granada, but at the same time began to oppose the Somoza dictatorship and was even imprisoned for a short while for taking part in student protests.

It was at the age of 31 in 1956 that Father Cardenal says he experienced his conversion to Catholicism. ‘God simply showed himself to me as love,’ he explains. In May 1957, he became a novice at the Trappist monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemane in Kentucky, under the guidance of the poet and philosopher Thomas Merton.

‘Merton was the greatest religious and mystical influence in my life. He changed my rather traditional view of Christianity. When I met him he had already been living a monastic life for twenty years, but was very critical of the established church. His views were those reflected in the Second Vatican Council (1965), and he completely changed my views too,’ says Father Cardenal.

After almost two years at Gethsemane, he was forced to leave the Trappists because his health was suffering as a result of the strict monastic regime. Merton advised him not to continue in a monastery, but to try to found a small religious community, and after his ordination in 1962 this was what Father Cardenal did.

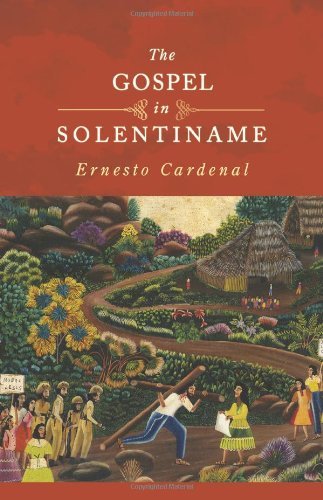

He founded this religious community at Solentiname among the archipelago of small islands dotted around the volcanic Lake Nicaragua. Here he taught the gospels to poor peasant farmers, while also helping them earn money from making handicrafts and producing vibrant paintings, often of biblical scenes transposed to rural Central America.

This simple life was shattered in 1977 when, following an attack on a National Guard barracks in the nearby town of San Carlos, the settlement at Solentiname was razed to the ground by members of the Somoza armed forces. Cardenal himself was forced to flee into exile in Costa Rica, where he became one of the Group of Twelve co-ordinating the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN) efforts internationally.

As a result, when the Sandinistas toppled the Somoza dynasty in 1979, Father Cardenal found himself as Minister of Culture in the revolutionary government. His brother Fernando, also a priest, was minister of education, while Father Miguel D’Escoto was appointed foreign minister. Once again, Father Cardenal sees no contradiction in the three priests’ active participation in politics: ‘We have to go on trying to make a revolution. Ever since the time of the prophets, people have been trying to achieve liberation, to free themselves from oppression, and to see justice and equality triumph. The prophets said it, and so did Christ.’

He was a Sandinista minister until 1984. Among his many activities, he tirelessly promoted the idea that everyone could write poetry, organising popular poetry workshops throughout the country. He also played a leading role in the nationwide literacy campaign, and oversaw the publication of cheap books in order to maintain the levels of literacy achieved. But, as he now admits: ‘I found the bureaucratic aspects of my position hard to cope with, and increasingly just wanted to get back to my writing.’

He continued to write throughout the years of revolutionary government, but like many other leading Sandinistas, he became disillusioned with the direction the movement took after its defeat in the 1989 elections. He left to join the Movement of Sandinista Renovation, which he says still supports ‘true Sandinismo and the true idea of revolution’. Although the Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega returned to power as president in 2006, Father Cardenal is scathing about his claims that he is continuing the Sandinista revolution in the same spirit as thirty years ago.

‘We are living under a dictatorship…the family dictatorship of Daniel Ortega, his wife and their children,’ he tells me, before abruptly falling silent. ‘I can’t say anything more, precisely because this is a dictatorship and I’m not at liberty to speak. I would suffer more reprisals like those I have already faced. I have a prison sentence hanging over me, and if I am not in jail now, it is only because in Nicaragua people over seventy do not have to go to prison.’

The sentence against Father Cardenal was for refusing to pay a fine imposed on him after a complicated land dispute in Solentiname. He has also had his bank accounts frozen, a move which he says is typical of the way that President Ortega’s government operates to stifle any opposition.

Despite these difficulties and the fact that he is still banned from saying Mass, Father Cardenal remains unwavering in his faith. ‘I feel the same faith now as I did in the Trappist monastery with Merton’, he says, ‘and because religion for me has always meant contemplation and working with a small community, I do not miss giving the sacraments. On Sundays I and a few others meet my brother Fernando, who is still a priest, to celebrate Mass together, and I still go regularly to Solentiname to encourage the community there.’

At eighty-four, he is also still writing poetry, and has just published another volume, Pluriverso. Earlier this year he travelled to Chile to receive the annual Pablo Neruda prize for poetry from President Michelle Bachelet. He admits to feeling a ‘lot of anguish as death draws closer, but also a profound belief in resurrection. That’s what I write about in my poetry these days. We are both man and God, and when we die we return to the part of us that is God.’

Volveré con un poco de lodo en los zapatos y una palabra alegre que decirte. ‘I will be back with a bit of mud on my shoes and a cheerful word to say to you.’ from Vida Perdida. Memorias I.1

Nor has he lost his belief that poetry is something that everyone can share. For the past two years, Father Cardenal has been helping to run poetry workshops at a Managua hospital where children with cancer receive treatment. A book of the children’s poems, Sin arcoiris fuera triste (How Sad It Would Be Without Rainbows) has just been published with financial aid of UNICEF. Father Cardenal’s prologue is a resounding statement of his beliefs: ‘All these poems are a hymn to the beauty of creation. Isn’t that the meaning of the universe, and why it was created? So that we can celebrate God’s creation, in which there are rainbows, tortoises, frogs, rabbits, ducks, the moon, snakes, parrots, children- and even children with cancer. But not so that we simply celebrate it and nothing more. No, above all so that we, along with everything else, may be resurrected, at whatever age we die. Christ gave us that pledge.’

Nick Caistor, Managua, Nicaragua October 2009

Main image: Ernesto Cardenal at his home in Los Robles. Image: Franklin Villavicencio/NiU