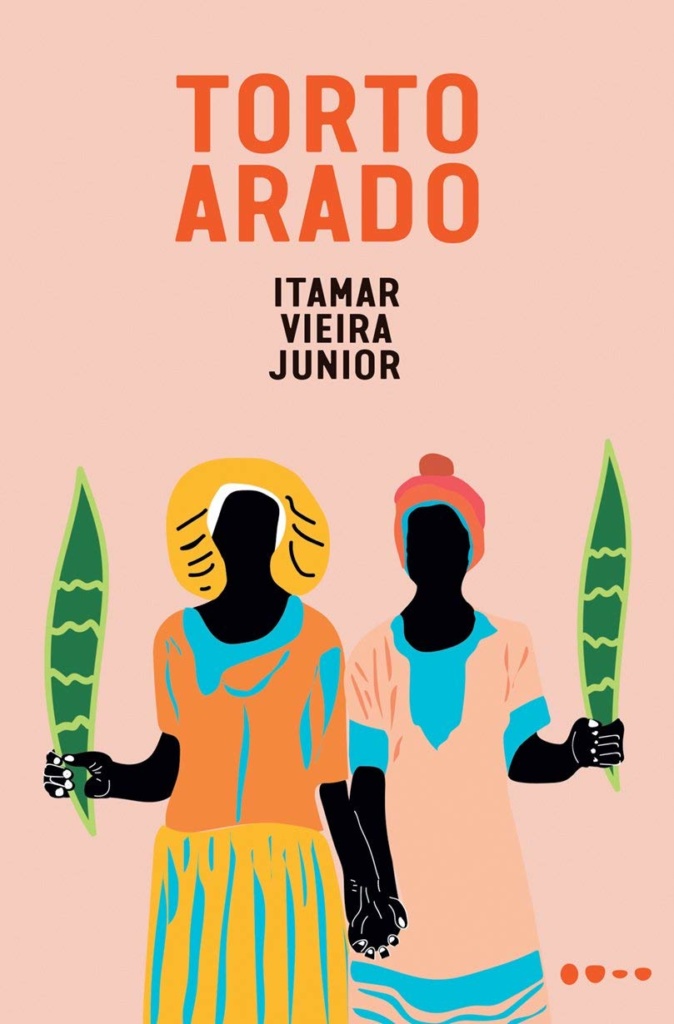

In gripping and evocative prose, Itamar Vieira Júnior’s ‘Torto Arado’ gives a voice to silenced black, indigenous and quilombola communities through the story of two sisters who find a mysterious knife under their grandmother’s bed, irrevocably changing their lives forever. This article was originally published in Sounds and Colours.

On May 13th 1888, Brazil became the last nation in the Americas to formally abolish slavery. Over 130 years later, hundreds of thousands of people are still living in modern slavery across the country.

Itamar Vieira Júnior is a writer from Brazil’s north-eastern state of Bahia. His multi award-winning debut novel ‘Torto Arado’ (Crooked Plough) is a beautifully written tour de force that unflinchingly gives a voice to the country’s silenced Black, Indigenous and Quilombola communities who have been fighting for their land rights for hundreds of years. ‘Quilombolas’ is the name for residents of Quilombos: settlements originally formed by fugitive slaves. There are roughly 3,000 Quilombos in Brazil today.

In gripping and evocative prose, Torto Arado tells the story of two sisters, Belonísia and Bibiana, and their family as they navigate the myriad hardships of rural life in Chapada Diamantina, in Brazil’s semi-arid sertão region. The family live on a ranch called Fazenda Água Negra (Black Water Ranch), and they are descendants of slaves for whom the abolition of slavery is no more than a date on the calendar.

One day, the sisters find an old, mysterious knife in a suitcase under their grandmother’s bed, and one of them accidentally cuts her tongue off – irrevocably changing their lives. From this moment, we see one of the central metaphors of the book: how Indigenous and Black communities are rendered invisible in Brazil’s rural northeast, far away from major cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. As the story unfolds, we meet their father, Zeca Chapéu Grande, who is a spiritual leader of the region’s Afro-Brazilian religion Jarê, which draws on other Afro-Brazilian traditions such as Candomblé and Umbanda.

The novel is split into three parts, namely Fio de Corte (Cutting Wire), Torto Arado (Crooked Plough) and Rio de Sangue (River of Blood), with each section narrated by a different character. Spanning three decades as the sisters grow up, they each form their own perspective: Belonísia seems to be content with life on the farm, whereas Bibiana recognises the injustice of her family’s life of unyielding servitude from an early age, leading her to set off and fight for change.

“Quando deram a liberdade aos negros, nosso abandono continuou. O povo vagou de terra em terra pedindo abrigo, passando fome, se sujeitando a trabalhar por nada. Se sujeitando a trabalhar por morada. A mesma escravidão de antes fantasiada de liberdade. Mas que liberdade?”

[Approximate translation: “When blacks were freed from slavery, we were still mistreated. We wandered about in search of shelter, going hungry, forced to work for nothing. The same slavery as before, masked as freedom. But what freedom?”]

Vieira Júnior is a writer who has experienced first-hand many of the themes explored in Torto Arado. Over the past 15 years, he has worked for Brazil’s land reform agency INCRA (National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform), which led him to live intimately with the Quilombola communities depicted in the novel, getting to know their stories, rituals and struggles.

In an interview to news portal UOL talking about his work with INCRA, Vieira Júnior said “they are communities that resisted, made up of slaves who went from place to place and, after abolition, formed families, communities, in a system of solidarity which is an example for all of us. It’s not a perfect system, but it stopped the State from decimating them.”

While Quilombola communities have certain rights guaranteed under Brazil’s 1988 National Constitution, this rarely leads to the granting of land titles. They have to apply to the INCRA to obtain titles to their lands, which is a slow, cumbersome and expensive process. Of the more than 1,700 Quilombolos in the process of gaining land titles through INCRA, only 181 have received titles, according to environmental news outlet Mongabay.

“Um dia, meu irmão Zezé perguntou ao nosso pai o que era viver de morada. Por que não éramos também donos daquela terra, se lá havíamos nascido e trabalhado desde sempre. Por que a família Peixoto, que não morava na fazenda, era dita dona. Por que não fazíamos daquela terra nossa, já que dela vivíamos, plantávamos as sementes, colhíamos o pão.”

[Approximate translation: “One day, my brother Zezé asked our father what it was like to live on your own land. Why weren’t we also the owners of the land if we were born there and had always worked there. Why were the Peixoto family, who didn’t even live on the farm, the owners. Why didn’t we make the land ours, seeing as we lived off it and planted our seeds there.”]

Vieira Júnior also draws on his own experiences growing up on the poor fringes of Salvador, the capital of Bahia, which is the city with the highest proportion of Black people in Brazil. His maternal great grandparents came to Bahia from Portugal as poor, illiterate immigrants in 1914.

In many interviews, Vieira Júnior has said that he seeks to write about the relationship between humans and the natural world: “We are talking about basic human rights. When we talk about the right to land, to territory, we are referring to the ground that we are standing on and it is a relationship that permeates everything. My background, as a geographer, of understanding the movement of people, makes me see a strong connection between us, humans, and the environment in which we live. The relationship between humans and the natural world was the focus as I was writing Torto Arado: a land which is often denied to certain people in multiple ways.”

In the past few years, Brazil’s far-right president Jair Bolsonaro has repeatedly denigrated and silenced the country’s Black, Indigenous and Quilombola communities. During his 2018 election campaign, he said that, once elected president, “not a centimetre of land would be demarcated for Indigenous and Quilombola communities.” One of his first decisions as president was to try to stop land reforms that would have benefited Quilombola communities. Bolsonaro’s rhetoric, in favour of developing rural areas, has emboldened illegal miners, loggers and land-grabbers to encroach on Quilombolos’ traditional lands. As a result, killings of Indigenous and Afro-Brazilians have increased.

The novel has been making waves on the literary scene both at home and abroad, and it is deserving of the many accolades it has won. When Torto Arado was first published in Portugal in 2018, it won the LeYa Prize, Portugal’s most prestigious literary prize. And in 2020, Vieira Júnior won two awards: he received a Jabuti Prize, the most traditional and prestigious literary prize in Brazil; and the Oceanos Prize, one of the most important literary prizes for books in the Portuguese language.

With his novel Torto Arado, Vieira Júnior joins a growing number of writers – such as Angolan-Portuguese writer Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida (author of That Hair) and Brazilian writer Ana Maria Gonçalves (author of A Colour Defect), whose work explores issues of colonialism, racism and identity. It is hard to overestimate the importance of novels like Torto Arado in a country like Brazil, where those who write are predominately white. Between 2005 and 2014, practically all of the Brazilian authors (97.5%) published by major publishers were white. This is in a country where white people only make up 47.73% of the population.

Torto Arado “portrays our current reality. I would love to say that it is a novel about a bygone period of our history, but that wouldn’t be true. Brazil today is the Brazil that is depicted in the book, which continues to kill those who dream of emancipation and social justice,” Vieira Júnior said in an interview with Portugal’s Público newspaper. It is an urgently powerful and personal manifesto against the silencing of Black, Indigenous and Quilombola communities in Brazil.

“Sobre a terra há de viver sempre o mais forte.”

Torto Arado was published by Todavia in 2019. The novel has not yet been translated into English.

Itamar Vieira Junior was born in Salvador, Bahia, in 1979. He is a writer, geographer and has a PhD in Ethnic and African Studies from the Federal University of Bahia, in which he researched the formation of Quilombola communities in the interior of the Brazilian northeast. He has published two collections of short stories in Portuguese: Dias (2012) and A Oração do Carrasco (2017).