- A new manifesto by eight of Brazil’s past environment ministers has accused the rightist Bolsonaro administration of “a series of unprecedented actions that are destroying the capacity of the environment ministry to formulate and carry out public policies.”

- The ministers warn that Bolsonaro’s draconian environmental policies, including the weakening of environmental licensing, plus sweeping illegal deforestation amnesties, could cause great economic harm to Brazil, possibly endangering trade agreements with the European Union.

- Brazil this month threatened to overhaul rules used to select deforestation projects for the Amazon Fund, a pool of money provided to Brazil annually, mostly by Norway and Germany. Both nations deny being consulted about the rule change that could end many NGOs receiving grants from the fund.

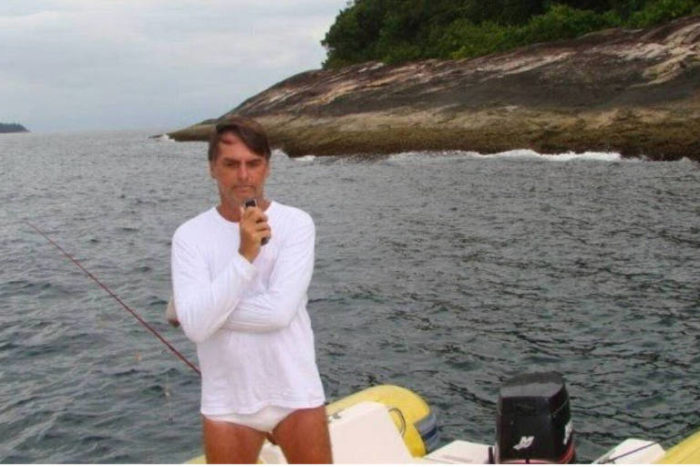

- Environment Minister Riccardo Salles also announced a reassessment of every one of Brazil’s 334 conservation units. Some parks may be closed, including the Tamoios Ecological Station, where Bolsonaro was fined for illegal fishing in 2012 and which he’d like to turn into the “Brazilian Cancun.”

- This article first appeared on Mongabay. You can see the original here.

Eight former Brazilian environment ministers launched a manifesto in São Paulo on 8 May in which they fiercely criticized President Jair Bolsonaro’s environmental policies.

In an unusual move, they condemned the administration for “a series of unprecedented actions that are destroying the capacity of the environment ministry to formulate and carry out public policies” and accused the government of “compromising the country’s international image and credibility.”

Among the measures they most strongly attacked is the decision to transfer the National Water Agency to the Ministry of Regional Development; the transfer of the Brazilian Forest Service to the Agriculture Ministry; the abolition of the Secretariat for Climate Change; the appointment of administrators with little or no environmental experience to key positions; and the weakening of environmental licencing under the pretext of achieving greater efficiency.

“We never thought that we would witness such an evil effort to destroy what Brazil has built over such a long period,” said Rubens Ricupero, environment minister from 1993-1994 under President Itamar Franco.

“The government is adopting policies that deny climate change,” warned José Sarney Filho, environment minister during the governments of Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Michel Temer. “It seems that we will need a huge catastrophe, a tragedy, for them to realize what is happening.”

“The country with the world’s greatest biodiversity is beginning to pull out of treaties it earlier signed,” said Carlos Minc, environment minister from 2008 to 2010 under President Lula in reference to the Paris Climate Agreement. “It may become the greatest threat to the planet’s climate.”

José Carlos Carvalho, environment minister in 2002, criticized Bolsonaro’s poor treatment of employees within, IBAMA, Brazil’s environmental agency: “It’s as if the [employees] are the cause of the problems they are meant to tackle,” he said, referring to the launch of investigations by the environment ministry against personnel assigned the task of combating illegal activities on indigenous lands and within protected areas, and threatening those employees with dismissal.

Brazil spurns international environmental initiatives

Marina Silva, environment minister from 2003-2008, and a 2018 presidential candidate, believes the slashing of budgets and the weakening of environmental licensing will cause great economic harm to Brazil: “The European Union is thinking twice about new agreements with Mercosul [South America’s trade bloc] because of our environmental policies,” she warned.

Edson Duarte, minister in early 2019 while Bolsonaro finalized the appointment of current Environment Minister Ricardo Salles, is concerned by the setbacks, saying: “Despite the different ideological positions of past [Brazilian] governments, they all brought advances [on the environmental front] but what we are seeing now is an irreversible process of unpacking the achievements of the last 40 years.”

He worries that international agreements made at the end of the Temer administration may be threatened. In particular, he mentioned large sums coming to Brazil via the Amazon Fund (roughly $87 million annually) to prevent deforestation, and the Climate Fund (roughly $105 million annually), which may not materialize now because major funding countries, especially Norway and Germany, are unhappy with Brazil’s sharp turn away from forest and climate protections.

On 17 May, Salles appeared to upset the two EU nations by unilaterally announcing an overhaul of the administrative rules for the Amazon Fund, claiming to have found irregularities in spending. Salles said that NGOs, whose deforestation and sustainability projects are monetized by the Amazon Fund, failed to account for more than $1.2 billion in spending. He also said that European funders had agreed that changes in the fund’s administrative structure are required. However, this version of events is denied by the European nations. “The Norwegian embassy said it had neither received nor agreed to any proposal [from Brazil] to change the management of the fund or the criteria for allocating resources,” according to reporting by the New York Times. Awards for Amazon Fund projects have stalled still since Bolsonaro took office in January.

The former ministers promised to follow up on their manifesto with action on the political and judicial fronts: “We will speak to the presidents of the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate and Supreme Court and take our document to the Attorney General’s Office,” said Ricupero. “We call on students to go out on the streets because their future is at stake.”

Environment Minister Salles responded with a statement in which he claimed that the harm to Brazil’s image is not the result of his policies but of “a defamatory campaign carried out by NGOs and supposed specialists.”

The Brazilian Rural Society (SRB), which represents agribusiness, also sprang to the government’s defense. It said: “The [environment] ministry has shown that it is capable of responding to the needs of the productive sector and contributing to the country’s development without relaxing the rigor of environmental legislation.”

Bolsonaro attacks Brazil’s conservation units

The administration continues intensifying its environmental assaults. Two days after the manifesto’s publication, Environment Minister Salles announced a reassessment of all of the country’s 334 Conservation Units — every protected area ranging from Itatiaia National Park, created in 1934; to the Little Blue Macaw Wildlife Refuge, created in 2018; which could potentially lead to the unraveling of Brazil’s environmental achievements of the last 85 years.

The 334 protected areas cover 9.1 percent of Brazil’s land territory and 24.4 percent of its marine waters. The degree of protection in the areas varies, with some benefitting from complete protection with rigid rules about access and use, while others permit various forms of sustainable economic exploitation.

The government’s main target at the moment seems to be the conserved areas with complete protection, where farming, ranching, fishing and mining are banned. Salles argues that “some of the areas were created without any kind of technical criteria,” and, as a result, Brazil is left with “all kinds of debts for unpaid compensation, and land conflicts.” He promises: “We’re going to put an end to this.”

NGOs have expressed strong opposition to the reassessment of the protected areas. “Salles’ proposal rewards criminals, those felling forest illegally and land thieves who historically have invaded and devastated protected areas,” says Angela Kuczach, who heads the Rede Pró-UCs, a network of environmental NGOs that defends the conserved areas.

She says that, contrary to what Salles claims, Brazil invests heavily in technical and scientific studies before it creates protected areas. “The map of protected areas, which Salles intentionally deleted from the ministry’s website, [was created using] one of the [world’s] most robust methodologies for assessing conservation priorities.”

Others speak of the damage that will be done to various societal sectors: “Along with irreversible environmental damage, the country will suffer serious economic harm if this policy is implemented,” says Maurício Guetta, the legal adviser to the nation’s leading NGO, the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA).

The administration’s preferred way of introducing drastic changes to past environmental policies is via Provisional Measures (MPs), a presidential decree. However, Guetta notes that Bolsonaro will need to pass a bill in Congress to introduce wholesale changes to the status of protected areas. “The Supreme Federal Tribunal (STF) has determined that [changes in protected areas] cannot be made by a provisional measure,” explained Guetta.

Despite this, Bolsonaro is expected to go on using his presidential powers to force the issue. He, for example, plans to revoke the decree creating the Tamoios Ecological Station, where he was fined for illegal fishing in 2012. He wants, he says, to turn the preserve into a “Brazilian Cancun,” a reference to the Mexican holiday resort. This would be a radical move; under current legislation, Tamoios, as an ecological station, enjoys full protection.

Ruralist deputies are also pressing for the Lagoa de Peixe National Park in southern Brazil — now an important feeding place for migratory birds arriving from the Arctic — to be turned into a wind farm.

The government has already announced plans to relax environmental protections in the Campos Gerais National Park in Paraná state, and in the National Forest of Jamanxim in Pará state. Jamanxim has long been under heavy assault by land grabbers and illegal deforesters.

Salles says the first measures involving conservation unit reassessments can be expected in the second half of this year.

Further amnesties for illegal deforestation

On the same day the former environment ministers met in São Paulo to draw up their manifesto, the bancada ruralista agribusiness lobby within a congressional commission managed to get approval on a sharply revised version of Provisional Measure (MP 867/2018). That MP was originally drawn up to extend by one year the period in which landowners accused of past environmental crimes, particularly illegal deforestation, could commit to compensation via reforestation as required by law.

However, while MP 867/2018 was making its way through Congress, amendments were attached that changed its original intent, turning it into a sweeping amnesty for landowners who have deforested illegally. This, critics say, is a maneuver used before by ruralists to push through controversial measures that lacked public backing?

While not affecting the Amazon, the amendments would greatly ease penalties for illegal deforestation carried out within four other Brazilian biomes (the Cerrado, Pantanal, Caatinga and the Pampa), all of which have areas where agribusiness is advancing aggressively. The amendments would no longer require offenders to reforest 20 percent of their property and leave it untouched as a “legal reserve.” The amendments would also abolish the fixed period of time by which landowners need to accomplish environmental restoration, which, in practice, would mean that offenders could ignore ever meeting the law’s requirements.

Such changes, if finally approved, could have hugely negative deforestation consequences. The Observatório do Código Florestal, a network of environmental NGOs, believes that the revised MP will exempt landowners from reforesting five million hectares (19,305 square miles), an area bigger than Denmark.

Federal deputy, Sérgio Souza, from Paraná state, who is the rapporteur of MP 867/2018, justifies the amendment changes, arguing there is legal disagreement over how, legislation regarding the 2012 Forest Code is to be implemented. “We are simply making it clear which law should be applied,” he said.

Others disagree. Federal deputy Rodrigo Agostinho protested, saying the amendment overrules, without proper debate, the deal that was hammered out in great detail by Congress and institutionalized in the 2012 Brazilian Forest Code style=”text-decoration: line-through”>.

Still, the battle is not over; the revised amendment now has to be approved by the plenaries in the Chamber of Deputies and in the Senate. Federal deputy Nilto Tatto said: “We’ve suffered a defeat in the commission, but we’re now going to take the battle to the plenary. And we will only lose there if society, organizations and the population fail to mobilize.” However, overturning the amendments won’t be easy; while Bolsonaro’s popularity is plummeting with the national populace, the powerful ruralist lobby in Congress still backs him.

Indigenous People achieve partial victory

The administration is not getting it all its own way. A day after the vote on MP 867/2018, a mixed Congressional Commission approved another report ordering the Bolsonaro administration to return its indigenous agency, FUNAI, to the Justice Ministry. That transfer includes FUNAI maintaining responsibility for the demarcation of indigenous land, which in a highly controversial move, Bolsonaro had earlier transferred to the Agriculture Ministry.

The handing back of FUNAI to the Justice Ministry had been one of the main demands of the Acampamento Terra Livre, an indigenous encampment and protest that took place in Brasilia at the end of April and brought together thousands of indigenous people from all over the country.

The congressional decision could, however, still be reversed, because the commission’s report has to be approved by the plenaries in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. But this partial success lifted the spirits of activists, demoralized by the recent series of extensive socioenvironmental setbacks, and may well encourage further mobilization of resistance.