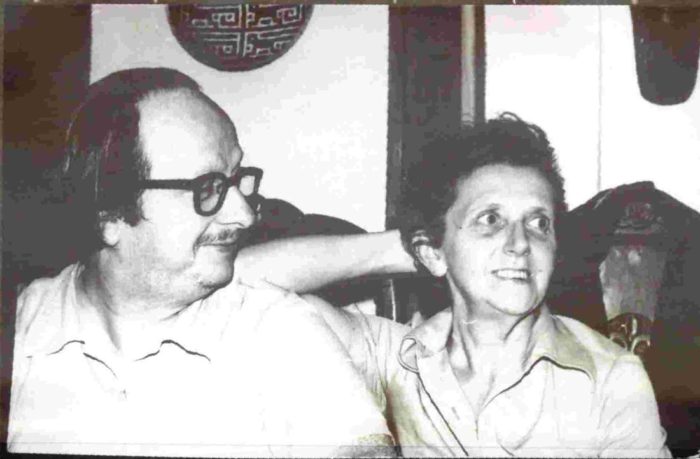

In the second article about the CAMeNA history archive in Mexico (you can read the first here), Cornelia Gräbner focuses on the life and work of the archive’s founders, Argentinian writer Gregorio Selser and his partner Marta Ventura.

The poet Juan Gelman described journalist and writer’s Gregorio Selser’s life as ‘a lucid and patient work to rescue everything that nurtures the cause of liberty and justice in Our America, to implacably reveal the manoeuvres and lies of its local and foreign oppressors.’ Selser was born in 1922 in Buenos Aires to Ukrainian-Jewish parents. He published over 40 books, countless newspaper articles, and worked for newspapers and news agencies in Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico, and Panama, among other places.

Selser and his partner Marta Ventura also assembled a large and wide-ranging archive, which covers all aspects of the ‘causes of liberty and justice in Our America’, and probes the ‘manoeuvres and lies of its local and foreign oppressors.’ This archive became the core holding of what would become CAMeNA.

Those who knew Selser remember his intellectual sharpness, his astuteness, and his implacable integrity. For his contemporaries he was the man of paper – especially newspapers, bundles of which he carried around with him. From these he extracted clippings with a razor, analyzed and synthesized the information gathered from this vast array of sources, set them in historical context, examined their implications for the future, and expressed all this in writing for his captive audiences, mostly in short non-fiction books.

His apartments – first in Buenos Aires, then in Mexico City – were filled with piles of documents and newspaper clippings. Those were occasionally knocked over by pets, navigated around by three daughters, and ordered and administrated by Marta Ventura.

Marta’s visual and spatial intelligence was as keen as Gregorio’s verbal and synthetic intelligence. She held the metaphorical key to the knowledge stored in the archive: she structured and ordered the material, and navigated the files and folders with competence, ease and efficiency.

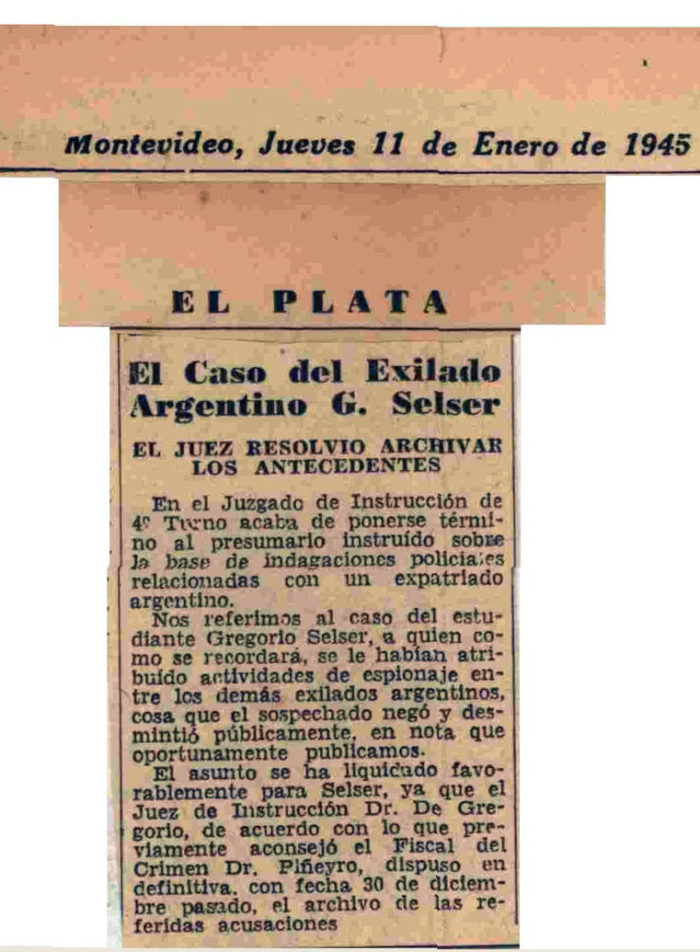

Selser’s political and ethical integrity crystallized around anti-fascism in the early 1940s. He got involved with organisations that supported the Spanish Republic, raising awareness and collecting donations. The police arrested him in the 1940s. After his release, Selser went into exile for the first time, to Uruguay. Returning to Argentina, he became the personal assistant of Alfredo Palacios, the first Socialist deputy of the country, and then turned to journalism.

Selser’s analytical mind was trained by an early (non-formal) education in literature. Orphaned at an early age he entered the working world after a minimum of formal education, because he felt that education distracted him from reading.

By the age of 15, he had read most of the works of Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, Emil Ludwig, Erich Maria Remarque and Leonhard Frank, as well as classics of committed literature, such as Les Misérables and Germinal.

He eventually finished secondary education at night school; but his approach to social and political realities was permanently marked by the teachings of great writers.

He recognized and discerned the complex plots and subtexts of social and political realities, as well as the connections between them, whether they were obvious, hidden or opaque.

He also had a keen eye for individual and collective characters that were shaped by, expressed, and in turn shaped their social realities.

His first two books showcased these abilities. They recovered from obscurity the figure of General Augusto Sandino and his ‘small crazy army’, who fought for the liberation of Nicaragua in what appeared impossible circumstances, against an array of overwhelming opponents – and won.

Sandino, General de Hombres Libres was written after the U.S.-orchestrated coup against democratically elected president Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954. Arbenz did not call the population – which widely supported him – to arms, to defend his government against the golpistas.

Sandino, in Selser’s biography, was the counter-example. At a moment when the cause of liberty and justice had just received a devastating blow, Selser’s book restored to many Latin Americans a largely forgotten figure who would now inspire and encourage people across the world.

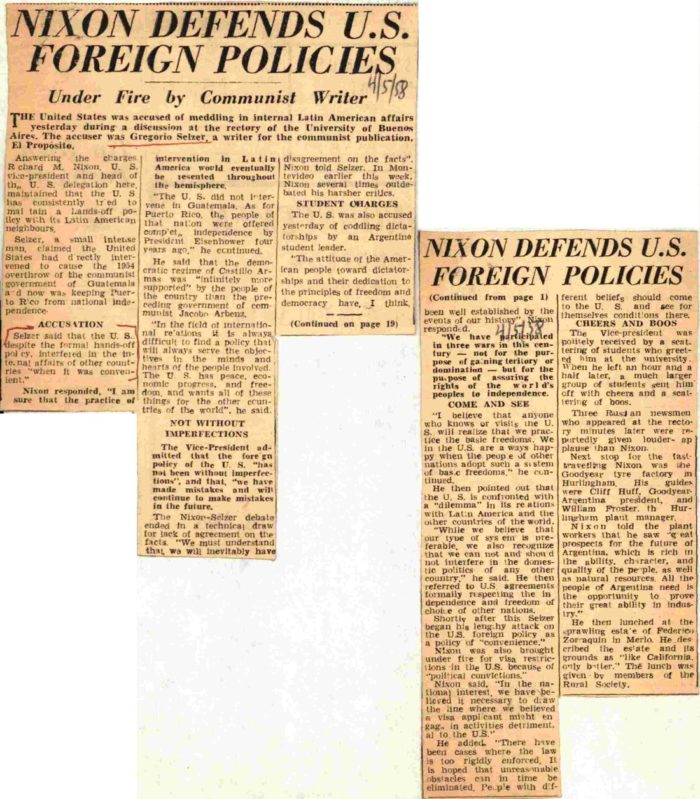

Confronting Nixon

Another incident typical of Selser was a public debate with Richard Nixon, then vice-president of the U.S., during a visit to Argentina in 1958, before the Cuban Revolution. At the time, Selser was registered for a degree at the University of Buenos Aires, and he took part in the debate as a student representative. When Nixon flat-out denied that the U.S. had intervened into Latin American politics, or had any intention of doing so, Selser responded:

‘We believe that the position of Mr Nixon regarding the non-intervention in the politics of Latin America is justified, but the facts have shown that words say one thing, and the tough reality with which the politics of the State Department come down on us are another. We don’t doubt the democractic sentiments of the North American people, but we do doubt those of the State Department when it comes to putting these desires into practice. … I will refer to the specific cases of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Paraguay and Nicaragua, where the US say they do not have the power to intervene, though they acknowledge the existence of dictatorships that oppress the people. How does this position go together with the attitude of the US towards Guatemala in 1954?’

Selser, a Socialist and Internationalist, did not pander to petty nationalisms. He fiercely opposed, exposed and criticized the State Department and international and multinational capitalist corporations. His solidarity he extended to oppressed people anywhere, including in the U.S., and he eventually published several books about their struggles 1)see also the biography by Julio Ferrer: Gregorio Selser – Una leyenda del periodismo latinoamericano, Prólogo de Stella Calloni, La Plata: Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social, 2018.

In this exchange with Nixon, Selser embodied the principled, articulate and outspoken Latin American intellectual who does not back down even in the face of a representative of world power.

Selser was keenly aware that the beginning of the Cold War marked an intensification of political repression and foreign intervention in Latin America. The US continued to see Latin American countries as their ‘backyard’, and intervened against any government considered to be ‘communist’. The US government’s understanding of that term was so loose that it came to encompass any movements or persons who strove for social justice.

At the same time, the U.S. encouraged and pressured regimes in Latin America to implement their National Security Doctrine, which stated that the enemy was now an enemy within, i.e. anyone involved in anything deemed ‘communist.’ The U.S. State Department itself engaged in secret and illegal military intervention, propaganda campaigns disguised as development aid, and training of locals who would then be deployed in Latin America.

Within Latin America, those struggling for self-determination, justice and liberty continued their work – at the state level, as political parties, as armed movements, social movements, or at local level as autonomous communities. This placed them into the firing line of those whose open repression and covert schemes Selser exposed, often as they were happening. Read from a 21st century perspective, Selser’s investigations of surveillance, propaganda, counter-insurgency and mega-projects are as relevant now as when he wrote them.

The Selser family suffered political persecution in Argentina even before the military coup d’etat in March 1976. They had to leave in haste shortly after, with Selser himself explicitly threatened and in great peril. They eventually found a new home in Mexico, where they remained.

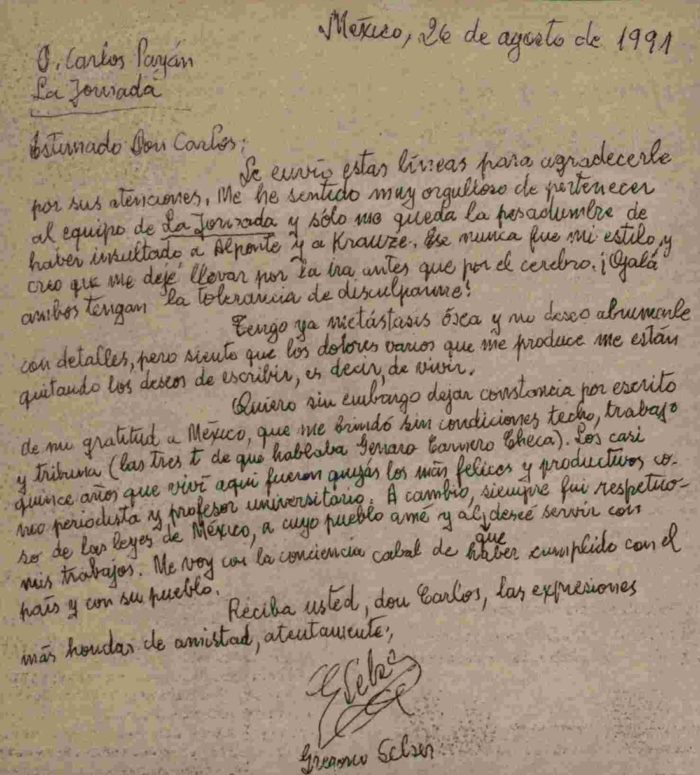

In Argentina, Selser had not always received the recognition he would have deserved. In Mexico, academic institutions and the journalistic world welcomed him into a stimulating environment for what was to become the most creative and productive period of his life. As mentioned in the previous article, his archive was eventually sent from Argentina by his political allies. Selser wrote and published until, in 1991, he was diagnosed with a debilitating and incurable form of cancer which would have curtailed his ability to write. He therefore chose to end his life in August 1991.

Marta Ventura and his three daughters – two of whom are also journalists – survived him and, in 2005, the archive was acquired by the Autonomous University of Mexico City. It has since been made available to the general public, and the materials collected by the Selsers have been complemented by those of others who, like them, nurture the cause of liberty and justice in Our América, and who implacably reveal the manoeuvres and lies of its local and foreign oppressors.

Main image: bookstall selling Cronología de las Intervenciones Extranjeras en América Latina by Gregorio Selser in Casa Lamm, 21 February 2011

All other images courtesy of the CAMeNA archive.

References

| ↑1 | see also the biography by Julio Ferrer: Gregorio Selser – Una leyenda del periodismo latinoamericano, Prólogo de Stella Calloni, La Plata: Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social, 2018 |

|---|