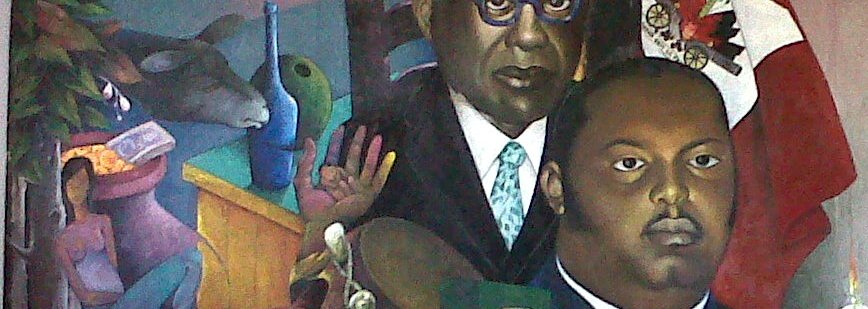

The decision in late February 2014 by the Haitian Court of Appeal that former dictator Jean-Claude (’Baby Doc’) Duvalier can stand trial for crimes against humanity represents a significant challenge for President Michel Martelly’s government.

The decision in late February 2014 by the Haitian Court of Appeal that former dictator Jean-Claude (’Baby Doc’) Duvalier can stand trial for crimes against humanity represents a significant challenge for President Michel Martelly’s government.

The Appeal Court’s decision reversed a January 2012 judicial ruling that Duvalier could not stand trial for such crimes because of the statute of limitations for the alleged crimes.

“There are obvious indications that Jean-Claude Duvalier indirectly participated and is legally responsible because he refrained from taking reasonable and necessary measures to prevent these crimes and punish those responsible,” Judge Jean Joseph Lebrun ruled.

The charges against 62-year old Duvalier include murder, illegal arrest, torture, and forced political exile of opponents of his regime. ‘Baby Doc’ is alleged to have used the paramilitary ‘Tontons Macoute’ militia to carry out these abuses.

Duvalier’s lawyer, Reynold Georges, had argued that that the statute of limitations in Haiti sets a maximum of ten years and therefore any alleged crimes committed twenty-five years ago could not be considered.

Moreover, international laws dealing with crimes against humanity which stipulate that a statute of limitations does not apply were invalid because such laws had never been ratified by any Haitian government.

Rule of law

The new Appeals Court decision has been widely applauded by human rights activists and by those who were victimised by the Duvalier regime.

Reed Brody, counsel for Human Rights Watch, was quoted in the Miami Herald as saying ‘We’ve seen Jean-Claude Duvalier be invited to presidential events and prancing around the country as if he were a VIP rather than an accused criminal. It’s an important affirmation of the potential of the rule of law’.

Duvalier succeeded his father François ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier as President for Life in April 1971 at the age of 19, and ruled the country until an uprising deposed him in 1986. He spent 25 years in exile in the United States and France before returning to Haiti in 2011.

Under Baby Doc, Haiti was widely seen as a kleptocracy. As poverty increased, Duvalier, his then-wife Michèle Bennett and his entourage amassed enormous personal fortunes. Money that had been given as aid to help the ailing Haitian economy was siphoned off into personal bank accounts.

In his account of Duvalierism, Haiti: State Against Nation, the Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot notes that ‘Duvalierists increasingly dipped into U.S. aid money, often without bothering to engage in any intermediate transaction to cover the embezzlement.’

Trouillot goes onto to describe a situation whereby particular duties and certain taxes were paid straight into the bank accounts of the Duvaliers. Het claims that in the fifteen years in which he was Haiti’s president, Jean-Claude Duvalier accrued a personal fortune in the region of $500 million.

Although Baby Doc’s regime was largely based on graft, he also kept the instruments and architecture of fear and terror that had helped to sustain his father in power for more than 15 years.

A report by Amnesty International from early 2014 refers to the ‘triangle of death’, a network of prisons including Fort Dimanche, where those who opposed the regime were held and often underwent beatings and other forms of torture.

No guarantees

Despite the appeal court giving the go-ahead to try Duvalier for the crimes that he committed while president, there is no guarantee that the government will press ahead with prosecution.

President Martelly has previously spoken of an amnesty for Duvalier, and his cabinet has a number of Duvalierists within it.

Francois Nicolas Duvalier, son of Jean Claude and grandson of François, works in the Presidential palace for President Martelly.

Martelly has also sought to rehabilitate Duvalier, inviting him, as well as other presidents including Prosper Avril and Jean-Bertrand Aristide, to various state events and ceremonies.

Duvalier’s presence alongside Martelly at an independence celebration in Gonaïves on January 1 2014 drew considerable criticism from observers of Haiti. Martelly justified his invitation to Duvalier by arguing that it was part of a project to achieve national reconciliation, to bring the past and present together.

The Martelly government also re-issued Duvalier with a diplomatic passport in January 2013.

Historic trial

Trying Duvalier for crimes against humanity will undoubtedly present challenges for Haiti’s under-funded legal system, and the trial would be the biggest and most significant in the country’s history.

Human rights advocates believe that, as well as providing the victims with their day in court and with the opportunity to seek restitution, such a trial could boost the credibility of the government and the legal system and would show Haitians that there is justice in Haiti.

As Reed Brody wrote in a piece in the Miami Herald (subsequently published on the Human Rights Watch website) ‘the prosecution of Duvalier could kick-start the system and help to begin building the state institutions that Haitians deserve.’