Since 2009, when the elected president Manuel Zelaya was ousted in a coup, 32 journalists have been killed in Honduras, the country with the highest homicide rate in the world.

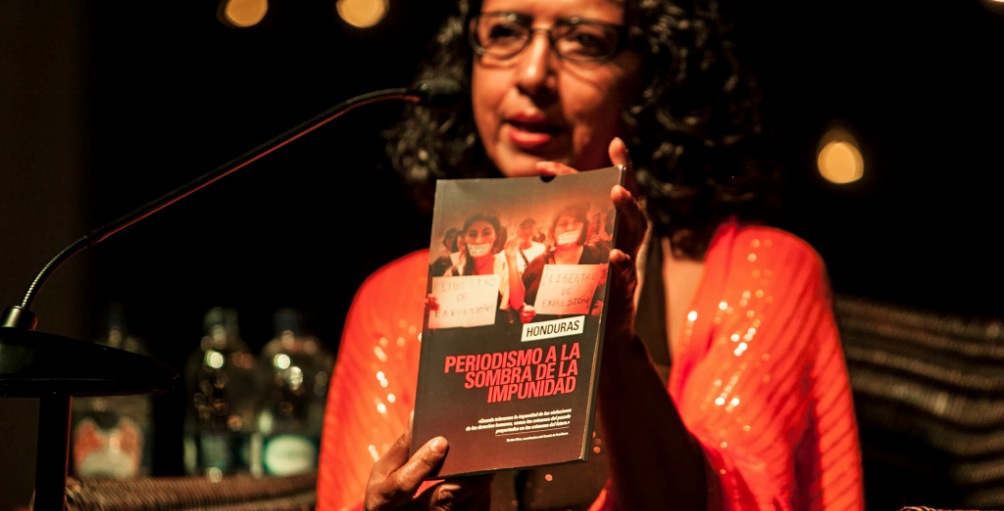

This is the reality revealed in the PEN International report “Honduras: Journalism in the Shadow of Impunity”, which Honduran human rights defender and journalist Dina Meza is helping to present this week (25 March 2014) to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington.

According to Ms. Meza, the most dangerous issues journalists in Honduras have to deal with are corruption, drug trafficking, organized crime and human rights violations.

According to Ms. Meza, the most dangerous issues journalists in Honduras have to deal with are corruption, drug trafficking, organized crime and human rights violations.

‘These issues are very complicated to cover. There are people who don’t like us covering these issues, and the big problem is that the Honduran state is corrupted by organized crime and drug traffickers’, Dina Meza said in an interview with LAB in London.

New president of Honduras

Elections were held in November 2013 to replace President Porfirio Lobo, who was elected in the wake of President Zelaya’s removal from office. The human rights situation in Honduras worsened considerably under his presidency. In 2013, the murder rate is reported at 79 per 100,000 people, a total of 19 murders per day.

The new president Juan Orlando Hernández, who took office early in 2014, has promised to change this situation.

‘In the coming months there will be a reduction in the number of homicides, acts of violence and extortions,’ Hernández said during his inauguration in the capital Tegucigalpa, although he gave little explanation as to how he hoped to achieve this.

‘Hernández came to power through fraudulent elections,’ said Dina Meza, although she expressed the hope that new political forces were now represented in Congress which could act as a counterbalance to the National Party government. ‘The people are demanding change. They have lost their fear, especially the young people.’

Harassment and threats

Since the late 1980s, Ms. Meza has been working as a journalist in the defence of human rights. In her view, the situation has grown steadily worse over the past two decades.

She herself has been a target for harassment and threats: ‘In 2006, I did an investigation about the labour rights violations of security guards. Firms didn’t pay them, they took away their days off, guards had to work 72 hours in a row…’

‘We published the story. I was threatened and sued, but eventually the case was dropped. After that I was offered bribes: holidays, flight tickets, and a villa to spend my holidays, but when I didn’t accept they started with direct threats. They told they would destroy the organisation I used to work for. They followed my children. I had to have bodyguards for six months.’

At the start of 2013, Meza was forced to leave Honduras after she had attended an international meeting about the violence against peasant farmers in the Bajo Aguán area in the north-east of the country.

‘I received new threats and had to move house because there were armed men trying to find me. They took pictures of me with my children. Finally I decided I had to leave Honduras.’

Violence and impunity against journalists and women

According to the PEN report Dina Meza is presenting to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the greatest problem is that murders and other serious crimes are rarely investigated, and even more rarely lead to prosecution.

‘The former Attorney General said that just a 20% of the murders were investigated, so the other 80% didn’t have any investigation at all. Human rights organizations estimate that impunity is even higher, around 95%,’ said Meza.

‘The police conceal statistics to say that security is improving. For example, they hide the female homicide rate. In Honduras, every one hour and fifteen minutes, a woman is murdered,’ according to Meza.

Meza combines three of the worst things to be in Honduras: journalist, woman and human rights defender: ‘The patriarchal system still prevails within the Honduran society, where violence against women and femicides are commonplace.’

Despite the threats against her, Meza will return to Honduras after presenting the PEN report. Her reasons for this are clear: ‘I cannot look at my children and tell them that I couldn’t do anything for this country, because that feeling is stronger than any gun or bullets of the police forces. That’s why we have to keep on with the struggle.’

As the PEN report concludes: ‘Until the Honduran state, and its regional and international partners, prioritise holding violators of human rights to account, impunity will remain the order of the day, and the crimes of the past will continue to foreshadow the crimes of the future.’