LAB Editor Javier Farje, who was in Caracas until March 3, where he found Chávez ‘everywhere’, reflects from Buenos Aires on the man and his legacy. Click here for Javier’s other blog posts from his travels in the region.

Few Venezuelans really believed the conspiracy theories that proliferated in recent days: Chávez had died in Cuba, Chávez was already dead , Chávez had been poisoned. And yet the mystery surrounding his illness — the sketchy medical report and the lack of photos — made it difficult for them not to believe that something strange was happening. And, in the midst of theories and rumours, Venezuelans didn’t seem to realise that, when their president flew to Cuba in December, it was probably the last time they would see him alive.

I spent a great deal of my time in Caracas asking that question of people I met. “Do you realise that a you may never see again the man whose presence has been almost intrusive for 14 years?” That would be enough to prompt a subdued silence, even among those who could not wait for him to die. Hugo Chávez has dominated the life of Venezuela for more than a decade. He changed the way things were done and said. And even those who have attacked him for almost everything that goes wrong under the sun told me that, indeed, in a weird sort of way, he would be missed.

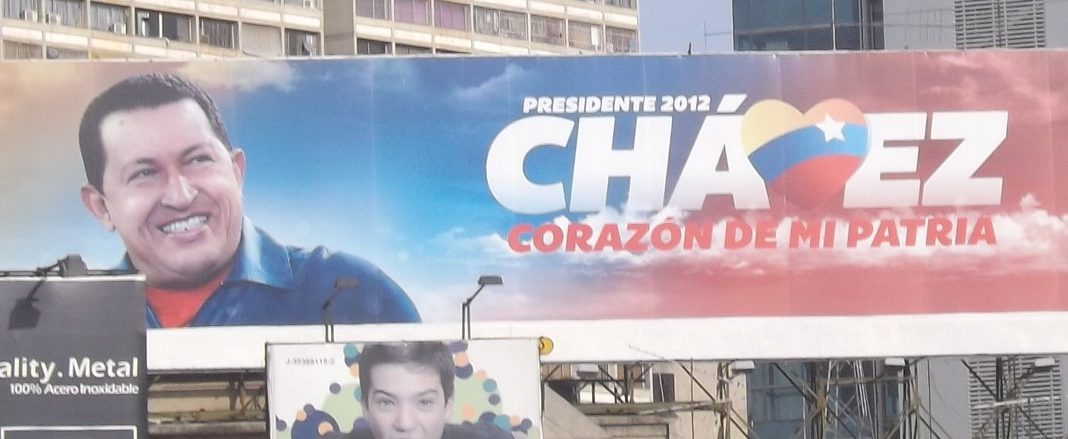

When I arrived in Caracas, I drove along streets full of posters depicting Chávez, Bolivar or the “Bolivarian Revolution”. In poor neighbourhoods, crudely drawn pictures of Chávez reminded people that he was everywhere.

My host Luis, with whom I am at present working in Argentina, told me this morning that what Chávez did was to give the streets back to common people. Before he was president, the middle classes would see the shantytowns, which surround Caracas like an iron belt, as part of another country. Chávez told ordinary people to take back the streets. And they did.

In Caracas I met with some leaders of the misiones, the community projects created by the Chávez government to give education, health and work to people who could not read, to stop them dying of a preventable disease or to give them the funds to start a small business. They spoke about these misiones as if they were what had allowed them to join the 21st Century. Even UNESCO has said that the misiones have helped Venezuela to meet some of the Millennium Development Goals. And UNESCO can hardly be accused of being a Chávez lackey.

Hugo Chávez changed the two-party system that prevailed before his election in 1998. Until then, the Christian Democrats of COPEI and the Social Democrats of Acción Democrática completely dominated. Chávez created the Unified Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) and made it the backbone of his government. When you walk in the Plaza Bolivar, the main square of Caracas, complete with an equestrian statue of Bolivar, you can see old people, wearing the red shirt of the PSUV, watching videos of the life of Bolivar.

And yet, Chávez showed the utmost intolerance towards those who did not share his ideals. He used an old-fashioned rhetoric of anti-imperialist slogans, cheap gags, insults and threats. And for all his attacks on the US government, especially on George W Bush, his country sold oil and refined petroleum products to the US. That never changed. Chávez simply charged higher prices than his predecessors.

His death has already caused some worrying trends. Not long after Vice-President Nicolas Maduro announced, with tears, that Chávez had died, the Defence Minister, Diego Molero, appeared before the cameras, wearing military field uniform and surrounded by uniformed generals. He praised Chávez and promised to defend the revolution and its leaders. It looked like an intimidating gesture, especially when the Electoral Commission is supposed to call for elections within a month of the death of the president, and it is up to the Venezuelan people to decide if they want to vote for Nicolas Maduro, Chávez’s heir, or Henrique Capriles, the opposition candidate who polled more than 40% of the votes in last year’s elections.

Chávez’s passing will also worry those who supported him in Latin America, mainly Bolivian President Evo Morales and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa. Morales was a protégé and pupil. After Chávez died, he appeared before the cameras to condemn those who had spent a great deal of time in the past two months demanding information about his friend’s health .

In the meantime, Venezuelan will have to live without Hugo Chávez. No more Sundays with 8-hour programmes where Chávez will talk endlessly about his revolution and his enemies. No more incendiary speeches, attacks on American imperialism, Chávez playing baseball, Chávez praying, Chávez hugging pensioners and children. The gigantic posters that hang from tall buildings will fade and his olive-green uniform will not be worn by anybody else. A kind of hush has descended on Venezuela. Nicolas Maduro, not a very popular leader among the chavistas, has the gigantic task of winning the next elections on behalf of his beloved leader.

Today, here in Buenos Aires, I interviewed an old Peronista senator, Lorenzo Pepe, a man who lived through most of Juan Domingo Perón’s last period in office in the mid 1970s, and he told me that, for him, Chávez is as important as Perón.

Say what you like about Hugo Chávez, Venezuela and in many ways Latin America will never be the same. Only history will decide if his country and the continent have changed for the better.

LAB Editor Javier Farje, who was in Caracas until March 3, where he found Chávez ‘everywhere’, reflects from Buenos Aires on the man and his legacy. Click here for Javier’s other blog posts from his travels in the region.

Few Venezuelans really believed the conspiracy theories that proliferated in recent days: Chávez had died in Cuba, Chávez was already dead , Chávez had been poisoned. And yet the mystery surrounding his illness — the sketchy medical report and the lack of photos — made it difficult for them not to believe that something strange was happening. And, in the midst of theories and rumours, Venezuelans didn’t seem to realise that, when their president flew to Cuba in December, it was probably the last time they would see him alive.

I spent a great deal of my time in Caracas asking that question of people I met. “Do you realise that a you may never see again the man whose presence has been almost intrusive for 14 years?” That would be enough to prompt a subdued silence, even among those who could not wait for him to die. Hugo Chávez has dominated the life of Venezuela for more than a decade. He changed the way things were done and said. And even those who have attacked him for almost everything that goes wrong under the sun told me that, indeed, in a weird sort of way, he would be missed.

When I arrived in Caracas, I drove along streets full of posters depicting Chávez, Bolivar or the “Bolivarian Revolution”. In poor neighbourhoods, crudely drawn pictures of Chávez reminded people that he was everywhere.

My host Luis, with whom I am at present working in Argentina, told me this morning that what Chávez did was to give the streets back to common people. Before he was president, the middle classes would see the shantytowns, which surround Caracas like an iron belt, as part of another country. Chávez told ordinary people to take back the streets. And they did.

In Caracas I met with some leaders of the misiones, the community projects created by the Chávez government to give education, health and work to people who could not read, to stop them dying of a preventable disease or to give them the funds to start a small business. They spoke about these misiones as if they were what had allowed them to join the 21st Century. Even UNESCO has said that the misiones have helped Venezuela to meet some of the Millennium Development Goals. And UNESCO can hardly be accused of being a Chávez lackey.

Hugo Chávez changed the two-party system that prevailed before his election in 1998. Until then, the Christian Democrats of COPEI and the Social Democrats of Acción Democrática completely dominated. Chávez created the Unified Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) and made it the backbone of his government. When you walk in the Plaza Bolivar, the main square of Caracas, complete with an equestrian statue of Bolivar, you can see old people, wearing the red shirt of the PSUV, watching videos of the life of Bolivar.

And yet, Chávez showed the utmost intolerance towards those who did not share his ideals. He used an old-fashioned rhetoric of anti-imperialist slogans, cheap gags, insults and threats. And for all his attacks on the US government, especially on George W Bush, his country sold oil and refined petroleum products to the US. That never changed. Chávez simply charged higher prices than his predecessors.

His death has already caused some worrying trends. Not long after Vice-President Nicolas Maduro announced, with tears, that Chávez had died, the Defence Minister, Diego Molero, appeared before the cameras, wearing military field uniform and surrounded by uniformed generals. He praised Chávez and promised to defend the revolution and its leaders. It looked like an intimidating gesture, especially when the Electoral Commission is supposed to call for elections within a month of the death of the president, and it is up to the Venezuelan people to decide if they want to vote for Nicolas Maduro, Chávez’s heir, or Henrique Capriles, the opposition candidate who polled more than 40% of the votes in last year’s elections.

Chávez’s passing will also worry those who supported him in Latin America, mainly Bolivian President Evo Morales and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa. Morales was a protégé and pupil. After Chávez died, he appeared before the cameras to condemn those who had spent a great deal of time in the past two months demanding information about his friend’s health .

In the meantime, Venezuelan will have to live without Hugo Chávez. No more Sundays with 8-hour programmes where Chávez will talk endlessly about his revolution and his enemies. No more incendiary speeches, attacks on American imperialism, Chávez playing baseball, Chávez praying, Chávez hugging pensioners and children. The gigantic posters that hang from tall buildings will fade and his olive-green uniform will not be worn by anybody else. A kind of hush has descended on Venezuela. Nicolas Maduro, not a very popular leader among the chavistas, has the gigantic task of winning the next elections on behalf of his beloved leader.

Today, here in Buenos Aires, I interviewed an old Peronista senator, Lorenzo Pepe, a man who lived through most of Juan Domingo Perón’s last period in office in the mid 1970s, and he told me that, for him, Chávez is as important as Perón.

Say what you like about Hugo Chávez, Venezuela and in many ways Latin America will never be the same. Only history will decide if his country and the continent have changed for the better.

CHAVEZ NO MORE

LAB Editor Javier Farje, who was in Caracas until March 3, where he found Chávez ‘everywhere’, reflects from Buenos Aires on the man and his legacy. Click here for Javier’s other blog posts from his travels in the region.

Few Venezuelans really believed the conspiracy theories that proliferated in recent days: Chávez had died in Cuba, Chávez was already dead , Chávez had been poisoned. And yet the mystery surrounding his illness — the sketchy medical report and the lack of photos — made it difficult for them not to believe that something strange was happening. And, in the midst of theories and rumours, Venezuelans didn’t seem to realise that, when their president flew to Cuba in December, it was probably the last time they would see him alive.

I spent a great deal of my time in Caracas asking that question of people I met. “Do you realise that a you may never see again the man whose presence has been almost intrusive for 14 years?” That would be enough to prompt a subdued silence, even among those who could not wait for him to die. Hugo Chávez has dominated the life of Venezuela for more than a decade. He changed the way things were done and said. And even those who have attacked him for almost everything that goes wrong under the sun told me that, indeed, in a weird sort of way, he would be missed.

When I arrived in Caracas, I drove along streets full of posters depicting Chávez, Bolivar or the “Bolivarian Revolution”. In poor neighbourhoods, crudely drawn pictures of Chávez reminded people that he was everywhere.

My host Luis, with whom I am at present working in Argentina, told me this morning that what Chávez did was to give the streets back to common people. Before he was president, the middle classes would see the shantytowns, which surround Caracas like an iron belt, as part of another country. Chávez told ordinary people to take back the streets. And they did.

In Caracas I met with some leaders of the misiones, the community projects created by the Chávez government to give education, health and work to people who could not read, to stop them dying of a preventable disease or to give them the funds to start a small business. They spoke about these misiones as if they were what had allowed them to join the 21st Century. Even UNESCO has said that the misiones have helped Venezuela to meet some of the Millennium Development Goals. And UNESCO can hardly be accused of being a Chávez lackey.

Hugo Chávez changed the two-party system that prevailed before his election in 1998. Until then, the Christian Democrats of COPEI and the Social Democrats of Acción Democrática completely dominated. Chávez created the Unified Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) and made it the backbone of his government. When you walk in the Plaza Bolivar, the main square of Caracas, complete with an equestrian statue of Bolivar, you can see old people, wearing the red shirt of the PSUV, watching videos of the life of Bolivar.

And yet, Chávez showed the utmost intolerance towards those who did not share his ideals. He used an old-fashioned rhetoric of anti-imperialist slogans, cheap gags, insults and threats. And for all his attacks on the US government, especially on George W Bush, his country sold oil and refined petroleum products to the US. That never changed. Chávez simply charged higher prices than his predecessors.

His death has already caused some worrying trends. Not long after Vice-President Nicolas Maduro announced, with tears, that Chávez had died, the Defence Minister, Diego Molero, appeared before the cameras, wearing military field uniform and surrounded by uniformed generals. He praised Chávez and promised to defend the revolution and its leaders. It looked like an intimidating gesture, especially when the Electoral Commission is supposed to call for elections within a month of the death of the president, and it is up to the Venezuelan people to decide if they want to vote for Nicolas Maduro, Chávez’s heir, or Henrique Capriles, the opposition candidate who polled more than 40% of the votes in last year’s elections.

Chávez’s passing will also worry those who supported him in Latin America, mainly Bolivian President Evo Morales and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa. Morales was a protégé and pupil. After Chávez died, he appeared before the cameras to condemn those who had spent a great deal of time in the past two months demanding information about his friend’s health .

In the meantime, Venezuelan will have to live without Hugo Chávez. No more Sundays with 8-hour programmes where Chávez will talk endlessly about his revolution and his enemies. No more incendiary speeches, attacks on American imperialism, Chávez playing baseball, Chávez praying, Chávez hugging pensioners and children. The gigantic posters that hang from tall buildings will fade and his olive-green uniform will not be worn by anybody else. A kind of hush has descended on Venezuela. Nicolas Maduro, not a very popular leader among the chavistas, has the gigantic task of winning the next elections on behalf of his beloved leader.

Today, here in Buenos Aires, I interviewed an old Peronista senator, Lorenzo Pepe, a man who lived through most of Juan Domingo Perón’s last period in office in the mid 1970s, and he told me that, for him, Chávez is as important as Perón.

Say what you like about Hugo Chávez, Venezuela and in many ways Latin America will never be the same. Only history will decide if his country and the continent have changed for the better.

LAB Editor Javier Farje, who was in Caracas until March 3, where he found Chávez ‘everywhere’, reflects from Buenos Aires on the man and his legacy. Click here for Javier’s other blog posts from his travels in the region.

Few Venezuelans really believed the conspiracy theories that proliferated in recent days: Chávez had died in Cuba, Chávez was already dead , Chávez had been poisoned. And yet the mystery surrounding his illness — the sketchy medical report and the lack of photos — made it difficult for them not to believe that something strange was happening. And, in the midst of theories and rumours, Venezuelans didn’t seem to realise that, when their president flew to Cuba in December, it was probably the last time they would see him alive.

I spent a great deal of my time in Caracas asking that question of people I met. “Do you realise that a you may never see again the man whose presence has been almost intrusive for 14 years?” That would be enough to prompt a subdued silence, even among those who could not wait for him to die. Hugo Chávez has dominated the life of Venezuela for more than a decade. He changed the way things were done and said. And even those who have attacked him for almost everything that goes wrong under the sun told me that, indeed, in a weird sort of way, he would be missed.

When I arrived in Caracas, I drove along streets full of posters depicting Chávez, Bolivar or the “Bolivarian Revolution”. In poor neighbourhoods, crudely drawn pictures of Chávez reminded people that he was everywhere.

My host Luis, with whom I am at present working in Argentina, told me this morning that what Chávez did was to give the streets back to common people. Before he was president, the middle classes would see the shantytowns, which surround Caracas like an iron belt, as part of another country. Chávez told ordinary people to take back the streets. And they did.

In Caracas I met with some leaders of the misiones, the community projects created by the Chávez government to give education, health and work to people who could not read, to stop them dying of a preventable disease or to give them the funds to start a small business. They spoke about these misiones as if they were what had allowed them to join the 21st Century. Even UNESCO has said that the misiones have helped Venezuela to meet some of the Millennium Development Goals. And UNESCO can hardly be accused of being a Chávez lackey.

Hugo Chávez changed the two-party system that prevailed before his election in 1998. Until then, the Christian Democrats of COPEI and the Social Democrats of Acción Democrática completely dominated. Chávez created the Unified Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) and made it the backbone of his government. When you walk in the Plaza Bolivar, the main square of Caracas, complete with an equestrian statue of Bolivar, you can see old people, wearing the red shirt of the PSUV, watching videos of the life of Bolivar.

And yet, Chávez showed the utmost intolerance towards those who did not share his ideals. He used an old-fashioned rhetoric of anti-imperialist slogans, cheap gags, insults and threats. And for all his attacks on the US government, especially on George W Bush, his country sold oil and refined petroleum products to the US. That never changed. Chávez simply charged higher prices than his predecessors.

His death has already caused some worrying trends. Not long after Vice-President Nicolas Maduro announced, with tears, that Chávez had died, the Defence Minister, Diego Molero, appeared before the cameras, wearing military field uniform and surrounded by uniformed generals. He praised Chávez and promised to defend the revolution and its leaders. It looked like an intimidating gesture, especially when the Electoral Commission is supposed to call for elections within a month of the death of the president, and it is up to the Venezuelan people to decide if they want to vote for Nicolas Maduro, Chávez’s heir, or Henrique Capriles, the opposition candidate who polled more than 40% of the votes in last year’s elections.

Chávez’s passing will also worry those who supported him in Latin America, mainly Bolivian President Evo Morales and Ecuador’s Rafael Correa. Morales was a protégé and pupil. After Chávez died, he appeared before the cameras to condemn those who had spent a great deal of time in the past two months demanding information about his friend’s health .

In the meantime, Venezuelan will have to live without Hugo Chávez. No more Sundays with 8-hour programmes where Chávez will talk endlessly about his revolution and his enemies. No more incendiary speeches, attacks on American imperialism, Chávez playing baseball, Chávez praying, Chávez hugging pensioners and children. The gigantic posters that hang from tall buildings will fade and his olive-green uniform will not be worn by anybody else. A kind of hush has descended on Venezuela. Nicolas Maduro, not a very popular leader among the chavistas, has the gigantic task of winning the next elections on behalf of his beloved leader.

Today, here in Buenos Aires, I interviewed an old Peronista senator, Lorenzo Pepe, a man who lived through most of Juan Domingo Perón’s last period in office in the mid 1970s, and he told me that, for him, Chávez is as important as Perón.

Say what you like about Hugo Chávez, Venezuela and in many ways Latin America will never be the same. Only history will decide if his country and the continent have changed for the better.