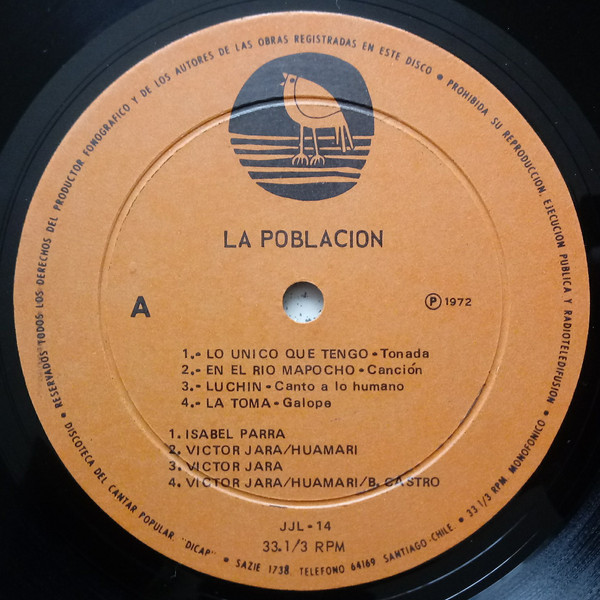

In 1972 the Chilean singer song writer Victor Jara released one of his final albums La Población. Its nine songs tell the stories of poor people living in a shanty town in Santiago, and provides an iconic musical testimony of their struggle for casa digna (decent housing). It featured voices from Herminda de la Victoria, then a shanty town but a community that has survived and which I visited in 2019.

The album, later ranked as one the country’s best albums, was soon banned under the dictatorship in Chile. Now, nearly 50 years after its first release, it will be celebrated in 2021 by the El Sueño Existe festival in Wales.

An album with a difference

By 1971 Victor Jara had produced six albums, and like others in the New Chilean Song movement, he used music to address social and political issues. In the account by his widow, Joan Jara 1)Victor, An Unfinished Song, by Joan Jara, (Jonathan Cape) Bloomsbury, London, 1983, this album would be a new departure, a sounding board for anonymous and deprived people. She describes how it came about, when by chance a compañero said ‘If you’re looking for something to sing about why don’t you make an album about our shanty town’. Victor spent weeks interviewing pobladores about their lives and communities, and included some of this testimony on the album.

Victor worked with playwright friend Alejandro Sieveking to develop the lyrics and involved established and new artists in the recordings. The album’s cover included a dedication to ‘the men and women who sacrifice their lives so their children can have a place to live’. It was produced by DICAP, the Discoteca del Cantar Popular, established in 1967, which distributed music that mainstream record producers in Chile would not touch.

The first three songs on La Población depict life on the margins of Chile at that time, when many people migrated to the capital, Santiago, and found no available housing. For years poor people in cities all around Latin America had occupied land, established squats and housed themselves as best they could,

The opening song describes one consequence of homelessness …. I would fall in love, when I do not have a place on earth. The second features the Mapoche river, on the banks of which some of Victor’s interviewees found a home back in the 1960s. There they would put up precarious shanties where the wind, the water, the houses bounce.

Luchín tells the personal story of one boy, ragged and fragile as a kite… with his little hands bruised, with the ball of rags, with the cat and dog – one of the many children Victor must have encountered. Yet he never forgets their potential: let us open all the cages, so that they fly away like birds.

While the children played, their parents were organising. They were part of the movement of pobladores, those who lived in poblaciones – low income residential settlements, typically with poor construction, minimal infrastructure and precarious tenure, often created in the first place by an occupation, a toma.

The toma

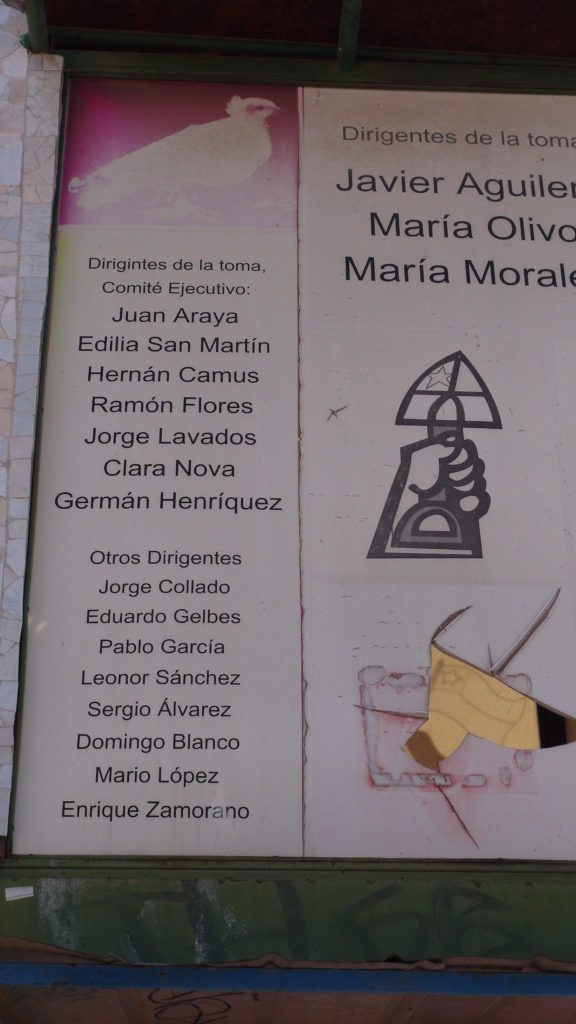

The toma at Herminda de la Victoria in March 1967 was well organised. In Chile homeless people’s groups, comités de los sin casa, encouraged people to take action, helped them to be well prepared, and ensured they would have external support. A comité in west Santiago prepared what would be the first large scale toma of the mid-1960s, and the names of the names of the leaders can still be seen in Herminda today.

Vacant land was identified and demands were issued, the pobladores wanting to show that they could improve their conditions through unity of action and hard work. But as they generally found, occupation was then a risky, even dangerous, activity.

The fourth song, La Toma, conveys the drama: The seizure has already started, compañero be quiet! and the danger: Soldiers in the morning.

Several hundred families, 648 according to Juan Araya, one of the leaders, gathered on the evening of 16 March. The album includes recorded testimony from a pobladora who explains that the intended location had been discovered by the authorities, so they had to find an alternative site. They must have been very well prepared if they could switch locations at the last moment.

Overnight the pobladores erected tents and shacks – hence why these tomas were known in Chile as poblaciónes callampas – mushroom communities. Any toma at that time was liable to be met by police attempting to evict them, and here hundreds of carabineros attacked using tear gas. The pobladores were cornered and cordoned off – we would call it ‘kettling’ today– but managed to hold on while the police initially refused to let in any supplies.

Within hours national and local politicians arrived on the scene, with Salvador Allende, at the time president of the Senate, trying to negotiate a solution. Images of some of these politicians can be found in murals in Herminda today, including then parliamentarian Gladys Marin, who was injured during the toma.

Visiting Herminda many years later I met people with vivid memories of that day. One named the police captain who ordered them to leave, adding that Allende said to hang on and stay calm. Another, who was a young child at the time, remembered many people in the tent encampment ‘singing the anthem of the homeless.’

Building a Community and casa digna

Having fought off the police, the pobladores planned to make use of a government scheme providing land for self-build. Negotiations continued while conditions deteriorated, and many pobladores fell ill and were hospitalised. Eventually the government agreed, and in return for regular payments, the families would receive land and infrastructure, with the promise of land titles later. After nine weeks of precarious existence they moved to a new 27 acre site, to set about building decent homes.

According to Joan Jara, one of the first of the leaky shacks to be built on the new site was for the prostitutes, and this was the subject of the first song on side two of the album, ‘Carpa de las coliguillas’, giving voice to these pobladora women: We are all waiting, Let the young and single arrive.

There was no drinking water, electricity, main drainage or paved roads. The next song pays tribute to the resourcefulness and abilities of the people who created Herminda and places like it: I can turn my hand to anything: I work for them as a carpenter, as a plasterer and a bricklayer, as a plumber and carpenter. Solidarity is vital: I’m not alone, because now we are so many.

Why Herminda?

The community is still remembered by its name. Herminda Álvarez Chávez was a baby who died soon after the toma. Some say she was shot by the police, but most likely she died of illness and the poor access to medical services experienced by many in Chile at that time.

Naming the new community in memory of the baby and the victory of the people helped to unify the group at a difficult time. Her death would not be in vain, and their sacrifices would lead to victory, their suffering and organisation allowing them to create a home of their own.

The seventh track is a lullaby for the child who died before she had chance to struggle. It also describes the transformation the población made possible – in words that I found on one mural: ‘born in the middle of mud, grew up like a butterfly, on seized land’.

Song eight called Rolling up our sleeves recognises how the pobladores through hard work could create dignified lives and homes, but suggested they could also have fun: this is not an occupation, it looks like a party. Over the years there would be many parties and celebrations at Herminda.

The final track is a march of the pobladores, as they celebrate their struggle and achievements, and look to the future: ‘With a roof, life is much better,let’s always work together and Chile will be a great home.’

Victor started work on La Población around five years after the toma. By this time the pobladores of Herminda had provided an example which was followed by hundreds of other tomas around Chile where homeless people would take direct action to establish their homes. For the three years 1970–73, making Chile a great home had been the task of the Popular Unity government led by Salvador Allende. Much seemed possible. But that was about to change completely.

When the music stopped

Barely a year after its launch, the album Población was banned in Chile, Victor Jara was arrested and murdered by the military, and poblaciones like Herminda were targeted for repression. Communities created by tomas, and those that supported them, would suffer from military attacks, disappearances and the murder of their leaders. Residents of Herminda I spoke to remembered the terrifying years of the dictatorship, one telling me that ‘you had to be prepared to see horrible things’ including bodies in the Mapocho River Victor had sung about.

In 1980 Herminda pobladores carried out a remarkable act of resistance. They received further demands for payments, but had retained key documents showing that instead they should receive their land titles. One person showed me where residents, including her father, organised protests in front of what is today the Neighbourhood Council office. Only then, after confronting the dictatorship, did they finally receive their titles.

The Rettig report of 1992 (into deaths and disappearances under the dictatorship) lists one incident in Herminda, typical of the widespread repression of poblaciones the 1980s. In November 1985, on the second day of a mass mobilization, troops fired from a military truck as residents were participating in street demonstrations, resulting in the death of 24 year old worker.

Herminda staged one last act of defiance against the dictatorship, when Pinochet came to open a gym on the anniversary of the coup in 1988. As it passed through Herminda, protesters threw whatever they could find at his cortège, forcing it to halt. The response from troops and helicopters left many injured with bullet wounds.

Weeks later the country voted No, paving the way for the Concertación government to replace the dictatorship. Herminda survived and the album La Población could be freely played again. In 2008 Rolling Stone would name it as 17th in its list of Chile’s best albums.

Herminda today

Visiting Herminda over 50 years after the toma I found an established community with paved roads and services, very different from the shacks that Victor would have found. Most residents own their homes, and the area has benefited from investment in open spaces and leisure facilities.

The community retains a strong collective memory, its history told in many murals. The anniversary of the toma was regularly celebrated, with the 52nd (the most recent before the Covid pandemic), featuring the band Quilapayún.

After years of struggle and adversity, a spirit of solidarity remains, and as one resident summed it up ‘We have learnt to grow as a community. Out of poverty has come this richness’. I found that Herminda still has a Junta da Vecinos (Residents Association) and its President told me ‘We carry on in our own way sharing our unity and heritage as a poblacion. We love Herminda.’

All images, and the title video, courtesy of Malcolm Boorer.

El Sueño’s celebration: On 18 September the Victor Jara festival El Sueño Existe (the Dreams Lives On) will celebrate this unique album with a zoom event. This will include all the songs from the album, most of them recorded specially for the event by a variety of singers and musicians, both from the UK and Chile. It will also screen archive and contemporary film from Herminda together with testimony from the today’s community. It will include Spanish translation. To attend the event send an e-mail to: suenoexiste19@gmail.com

The El Sueño festival normally happens every summer in Machynlleth Wales, celebrating Chilean New Song and bringing modern politics, culture and struggles in Latin America closer to home. In 2022, from 5–7 August, it will focus on El Salvador, whilst remembering Victor Jara and La Población.

References

| ↑1 | Victor, An Unfinished Song, by Joan Jara, (Jonathan Cape) Bloomsbury, London, 1983 |

|---|