By Molly Hofsommer*

Commissioners: Rose-Marie Belle Antoine, Dinah Shelton, Rosa María Ortiz, Elizabeth Abi-Mershed (Assistant Executive Secretary)

Petitioners: Fergus McKay (Association of Indigenous Village Leaders in Suriname (VIDS)), Captain Richard Pené (Village Chief)

State: Suriname

Topic: Case 12.639 Regarding the Kaliña and Lokono indigenous peoples of Suriname

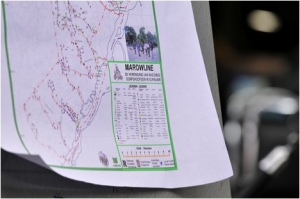

Map of Traditional Land Use of the Lower Marowijne Peoples, Suriname, Presented to the Commisison. Photo by Juan Manuel Herrera/OAS.On March 27, 2012, the Inter-American Commission held a hearing on Case 12.639, regarding the Kaliña and Lokono indigenous peoples of Suriname and their land rights. This case arises from petitioners’ claims that the indigenous property rights of the Lower Marowijne Peoples are neither recognized nor respected in the laws of Suriname. Petitioners claim that the State’s laws, in violation of the American Convention on Human Rights (Convention), vest ownership of all untitled lands and natural resources in the State, fail to provide adequate remedies for protection of indigenous property rights, and do not recognize the juridical personality of the Lower Marowijne Peoples for the purpose of holding land titles or seeking protection for their communal rights. Representing the petitioners were Captain Richard Pené, village Chief, and Fergus MacKay, Senior Counsel of the Forest Peoples Programme. Representing the State were Kenneth Johan Amoksi, Counselor/Alternate representative at the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Suriname, and Sachi Ramlala-Soekhoe, First Secretary/Alternate Representative of the Republic of Suriname to the OAS. Commissioners Rose-Marie Belle Antoine, Dinah Shelton, Rosa María Ortiz, and Assistant Executive Secretary Elizabeth Abi-Mershed were present.

Map of Traditional Land Use of the Lower Marowijne Peoples, Suriname, Presented to the Commisison. Photo by Juan Manuel Herrera/OAS.On March 27, 2012, the Inter-American Commission held a hearing on Case 12.639, regarding the Kaliña and Lokono indigenous peoples of Suriname and their land rights. This case arises from petitioners’ claims that the indigenous property rights of the Lower Marowijne Peoples are neither recognized nor respected in the laws of Suriname. Petitioners claim that the State’s laws, in violation of the American Convention on Human Rights (Convention), vest ownership of all untitled lands and natural resources in the State, fail to provide adequate remedies for protection of indigenous property rights, and do not recognize the juridical personality of the Lower Marowijne Peoples for the purpose of holding land titles or seeking protection for their communal rights. Representing the petitioners were Captain Richard Pené, village Chief, and Fergus MacKay, Senior Counsel of the Forest Peoples Programme. Representing the State were Kenneth Johan Amoksi, Counselor/Alternate representative at the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Suriname, and Sachi Ramlala-Soekhoe, First Secretary/Alternate Representative of the Republic of Suriname to the OAS. Commissioners Rose-Marie Belle Antoine, Dinah Shelton, Rosa María Ortiz, and Assistant Executive Secretary Elizabeth Abi-Mershed were present.

With respect to alleged violations of Article 3 (Right to Juridical Personality), Article 21 (Right to Property), and Article 25 (Right to Judicial Protection) of the Convention, the Commission declared the petition admissible on October 15, 2007 in Report Number 76/07.

Petitioners contend that the rights of the Kaliña and Lokono have been violated by the State in several respects. Between 1976 and 2006, approximately 20 land titles were issued by the State to non-indigenous persons over lands in four of the villages of the Lower Marowinjne Peoples. Additionally, Petitioners point to the three nature reserves established within the territory of the Lower Marowijne Peoples without the knowledge or consent of the inhabitants. According to Captain Richard Pené, these reserves have granted animals land rights over people’s land rights. However, concessions have been granted by Suriname for mining, logging, and oil exploration within the same nature preserves where the indigenous people are not permitted to “pick a flower.” In 1976, state claims that these villages were not actually indigenous communities but suburbs of a nearby town resulted in the subdivision of indigenous villages and issuance of title to private landowners.

Similar issues were brought before the Commission and ultimately the Inter-American Court on Human Rights in the case regarding the Twelve Saramaka clans. In the Saramaka case, the Commission requested that Suriname suspend logging and mining concessions in indigenous Saramaka Maroon territory. In its unanimous decision the Court stated that Suriname shall adopt measures to ensure that free prior informed consent where necessary to meet the rights of the Saramaka people, that all environmental and social impact assessments are conducted and published, and that damages be paid to a community development fund to benefit the Saramaka people.

After Petitioners’ presentation, representatives of the State shared with the Commission the laws in place that it claimed protected the rights of indigenous people. The State discussed the application procedure for land rights, the procedure for applying for concessions, and the various requirements taken into consideration when establishing communal forests. Ultimately, the State contends that indigenous people are recognized by the state.

As Special Rapporteur for Suriname and on Indigenous People, Commissioner Shelton identified the main problem in this situation as the State’s designation of traditionally indigenous lands as “state owned lands.” This is inconsistent with the Inter-American System where, for the security of tenure, the lands are to be titled to the indigenous people. Commissioner Shelton asked the State whether there are specific problems in passing legislation permitting titles to be granted and what the State is doing to comply with the judgments of the Saramaka Case. Commissioner Antione requested that the State provide an explanation as to how it defines and assesses what the public interest is (in relation to establishing environmental and nature programs) and Commissioner Ortiz asked whether any efforts have been made by Suriname to ratify International Labor Organization Convention 169 (dealing specifically with the rights of indigenous and tribal people).

Petitioners stated that the indigenous peoples needs are never considered when the public interest assessments are made because the rights of the indigenous people have never been recognized by the State. Petitioners noted the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court’s decisions go beyond what is stated in ILO Convention 169, and therefore, the State has existing and more extensive obligations than required by the Convention. The State informed the Commission that responses to the questions would be provided in writing after consulting with the headquarters. Commissioner Shelton concluded the hearing by offering to visit Suriname when appropriate.

* Source: Human Rights Brief http://hrbrief.org/