Learning a language always opens our eyes. Communicating in another language does not mean just translating word-by-word ideas and concepts, but rather this journey forces us to learn new ways of seeing the world. Let’s take, for example, something as simple as a greeting: “how are you?” The variations of this oh-so-common phrase can tell us a lot about a people’s culture. In Chinese (“ni chi fan le ma?”) and in Korean (“shiksa haeseyou?”), the equivalent of “how are you?” literally translates to “have you eaten yet?”. That tells us a lot about the central role food plays in these societies: wellbeing in strictly related to being well-fed. Because who can really be ok if they are starving?

In my third class in the mayan language K’iche’ (with the brilliant teacher María Yax in Guatemala), I learned the following dialogue:

A: Utz awech? (Literal translation: “Are you ok?” / Common use translation: “How are you?”)

B: Ma utz taj. (Literally: “I am not ok”.)

A: Jas mo ma utz ta awech? (Literally: “Why are you not ok?”)

How do I analyse this? As someone with a very modest background in linguistics (as well as someone who studied discourse analysis under the fantastic professor Dr. Fernando Castaños Zun of the National Autonomous University (UNAM) in Mexico), I can’t seem to leave this kind of thing alone.

What’s the difference between “How are you?” and “Are you ok?”. The reader may have their own ideas, and if so I would love to chat.

One difference that strikes me is that, at first sight, “How are you?” leaves open the possibility for a range of answers: “I’m ok”, “I’m tired”, “I’m sad”, “I’m hungry”, etc. But now let me put another issue on the table: of all the times we may ask “How are you?” in a day, how often are we really interested in the answer? How many times do we stop to listen?

Now let’s look at “Utz awech?” (“Are you ok?”). At first sight, it may appear to be a binary question that has only two possible answers: “yes” or “no”. But if we delve further there’s a complexity there: isn’t it true that we can simultaneously be ok in some aspects, and not ok in others? Here possibly the concept of aq’abal’[1] from Mayan Cosmovision comes in: an inter-weaving of good and bad, day and night, light and darkness. An important aside: as a Scot (who has lived in Guatemala for over eight years) I don’t assume, not now nor ever, to be able to speak with one grain of intellectual authority on Mayan Cosmovision… for that I would need a lifetime of cultural transmission of the invaluable Mayan ancestral wisdom).

What I want to reflect upon here is the centrality of “being ok”[2], which seems to me to be key with regards to “utz awech?” Right now, are we ok? With the pollution of our rivers (and here I use “our” to refer to the planet we share, Guatemala, the Mayan peoples, Europe, and beyond), the pollution of our seas and oceans, the destruction of our forests, violence, discrimination, poverty, famine… are we ok?

Guatemala, utz awech? Planet Earth, utz awech?

I would say no, we are not ok: Ma utzta uj k’olik. With climate change threatening the entire planet, and an economic system based on over-consumption (which could basically be considered a pillage of our natural resources), we are not ok. With a rate of infant malnutrition of almost 50% in Guatemala, a country that is considered ‘middle-income’ (which shows the stark inequality that exists in wealth distribution), we are not ok.

This leads me to the question: how is it possible that in the past 50 years we have done so much damage to a planet that has been around for millions of years? Part of the answer lies in my own educational background in Scotland. In our History classes in High School we began with the ‘Industrial Revolution’, as though anything that had happened before that was irrelevant. And with the UK having been one of the world’s main culprits for the scourge of colonialism, that word was not once uttered in High School.

So what? Why am I writing this? Because I want to advocate for a reclamation of that history (my own, as well as the Guatemalan) that so many generations have sought to silence. The Mayan people, for example, knew how to care for our planet over centuries (or even millennia). Aren’t we a bit stupid if we continue to turn a blind eye to all of that learning and wisdom?

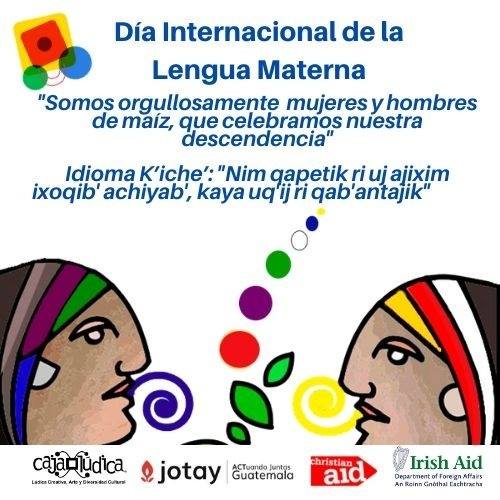

Caja Lúdica celebrates the International Day of the Mother Tongue, with a procession along Sexta Avenida of Guatemala City. The slogan was: “We are proud women and men of maize, celebrating our heritage” (“Somos orgullosamente mujeres y hombres de maíz, que celebramos nuestra descendencia”. In the k’iche’ language: “Nim qapetik ri uj ajixim ixoqib’ achiyab’, kaya uq’ ij ri qab’antajik” All images by Byron García/Prensa Libre. The full article in Prensa Libre can he seen here.

To begin to draw these threads together, an anecdote. I have a friend in Scotland who is an economist (with all the letters you want in front of his name). His first academic course of study was Physics, in which he obtained a Masters. He then completed a PhD in Economics. He’s never been to Guatemala, and knows little more of the country than the things I have told him over a bottle of wine. But we stay up to date with what each other is doing (I understand about 10% of what he tells me, but he’s still interesting to listen to). When I told him I was studying K’iche’, he shared something with me that fascinated me: that the calculations of celestial movements that the Mayan people managed to do (before the invasion by the Spaniards in the 16th Century), without knowing the laws of Physics, would take days or weeks with a modern computer which can do millions of calculations per second.

So I want to finish by thanking the Mayan peoples, on this, the Day of the Mother Tongue. Maltyox for the wisdom, maltyox for taking care of our planet, and, very personally, maltyox for this intellectual journey I am commencing.

Postscript: I realise that I have

zero authority to be able to talk about these issues, but I though that the

point of view of a foreigner learning K’iche’ might be of interest. Personally,

I pay careful attention to what the experts on these issues have to say: Mayan

peoples and academics. And to them also: Maltyox.

[1] Aq’abal’ is a day in the Mayan Calendar, and also one of the 20 nahuales, a concept in Mayan Cosmovision which could be roughly translated as “guiding spirits/forces”.

[2] By way of parenthesis: in other Mayan languages, such as Q’eqchi’ (Guatemala) and Tzeltal (Chiapas in Mexico), the equivalent of “How are you?” is “How is your heart?”. But that’s a matter for another essay.