Covid-19 has caused untold damage in Latin America. The region accounts for almost a third of Covid-19 deaths despite making up less than 10 percent of the world’s population. Many of the region’s economies also suffered disproportionately when compared to the rest of the world. While global production had contracted by approximately three per cent by May 2021, Latin America and the Caribbean stood at seven per cent. Argentina, Peru and Mexico were among the countries with the worst financial contractions in the world.

A pandemic of this magnitude came as no surprise. With SARS in 2003, H1N1 (Swine Flu) in 2009, Ebola in 2013, and then Zika and MERS, the world had dodged bullets several times over. Epidemiologists understood that at some point luck would run out, especially if a pathogen was fast-moving and transmitted asymptomatically. Globally preparedness remained low, despite increased attention by many in the scientific and specialized policy communities.

Explaining why Latin American countries suffered disproportionately is difficult; despite their unpreparedness for biological risks previous to the pandemic, Latin American countries were comparatively more prepared than other countries in the Global South. Nonetheless, studies about the pandemic in Latin America have pointed to two main reasons: political mismanagement and social inequalities.

If there is a silver lining, it is that a new consensus on the importance of pandemic preparedness seems to be emerging, fuelled by the human costs of unpreparedness. Yet despite the disproportionate effects of the pandemic in Latin America, the region is being left out of the picture.

Investing in people and fixing inequality can support preparedness

Social and material conditions in the region are critical to explaining the failed pandemic response in Latin America. Regionally, 60 per cent of citizens work informally, leaving them unable to access social benefits and thereby unable to afford to stay home. Latin America is also highly urbanized, with 80 per cent of the region’s population living in cities, and 20 per cent living in slums. In these environments, social distancing is difficult (if not impossible) and access to good sanitation facilities is a challenge.

High levels of urbanization and informal employment, impaired access to healthcare, and overall poverty had negative effects on the speed and size of the spread of the pandemic in the region. Even if governments did have an appetite to provide one-off financial support to citizens outside the reach of social safety nets, it was a struggle to identify and accurately support them. Amnesty International and the Center for Economic and Social Rights published a report in April 2022 attributing the tragic impact of COVID-19 in the region to social, racial and economic inequality.

Stronger social protection systems would have supported people staying at home, avoiding work and seeking medical care earlier if sick. Consider domestic workers, a highly informal and gendered sector where over 93 per cent of the over 18 million workers are women. Researcher Jorgelina Loza notes that only 24 per cent of domestic workers in the region get benefits from health or social security. As Loza points out, the first Covid-19 death in Brazil was a domestic worker who had to continue working at her employer’s home.

The pandemic highlighted the long-ranging impacts of inequality. In turn, recovery and preparedness should emphasize the social and material conditions which led to the region’s failure to cope with contagious bio-risks. Fiscal and social policies should support stronger social safety nets to support the most vulnerable populations during crises.

Trust matters for pandemic response and preparedness

The only two Latin American members of the Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness (Ernesto Zedillo, former President of Mexico, and Mauricio Cárdenas, Former Minister of Finance for Colombia) point to “wrong strategies and polices enacted by incompetent governments that miserably failed their citizens”.

Latin America has relatively low levels of trust in government and interpersonal trust, which impacts how governments can effectively enforce bio-risk mitigation and positive messaging. Global studies have shown that effective Covid responses relied on trust. Low trust hinders vaccine uptake and fuels conspiracy. The countries that failed to control spread often had eroded trust.

Given the relevance of effective communication, trust, and solid anti-misinformation systems for pandemic control, Latin American governments should investigate how the chronic lack of trust in institutions in the region threatens effective responses in the future. Policymakers should retrospectively and prospectively analyse approaches to community engagement and ownership, risk communication, and mechanisms to ensure transparency and accountability.

Strengthening health systems should be a priority

Most of the region’s healthcare systems are in need of greater investment. Compared to OECD averages, Latin American countries spend less on healthcare, have fewer healthcare professionals, and fewer hospital beds. While Mexico, Costa Rica, Colombia and Chile have the most beds in the region at 2.1 per 1000 people, that figure is less than half the OECD average.

Building resilience towards bio-risks will certainly require stronger health systems that can better cope with surges in demand. To that end, ensuring financing and investment towards universal coverage in the region should be a priority. Testing and laboratory capacity will also need to be strengthened in some countries. While some managed to set up relatively strong testing regimes, including national test production, others buckled under the pressure of mounting cases.

Improved coordination and regional leadership

The pandemic shed light on the anarchy of the international arena. Even at a time of crisis, countries shut their doors to each other in inconsistent ways, and vaccine nationalism prevented a truly strong response from taking place. The WHO’s COVAX Facility largely failed to rapidly provide lower income countries with access to much needed vaccines. Crucially, the process failed to include regional and country stakeholders in its design.

Coordinating monitoring capabilities and information sharing was also highlighted as a key area for improvement. While the region had a pre-existing regional testing and monitoring system set up by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in the wake of previous viral spreads like H1N1, the system faced problems such as a chronic lack of supplies. Some countries were able to improve their sequencing capabilities as a result of the regional system, but others countries failed to scale up their test capabilities.

As the pandemic recedes into the rear-view mirror, international coordination mechanisms are beginning to shape the future of bio-risk preparedness. Latin America, often overlooked in global conversations, needs to step up and insist on contributing meaningfully to the global preparedness conversation.

An open window of opportunity

While it is tempting to move on to more immediate issues related to economic recovery, the pandemic has highlighted the untold damage a contagious bio-risk can lead to in this highly unequal region. Now, there is a window of opportunity to invest in highly impactful preparedness measures. With research showing that even now the world is still woefully unprepared, Latin America must lead the way in safeguarding the livelihoods of future generations.

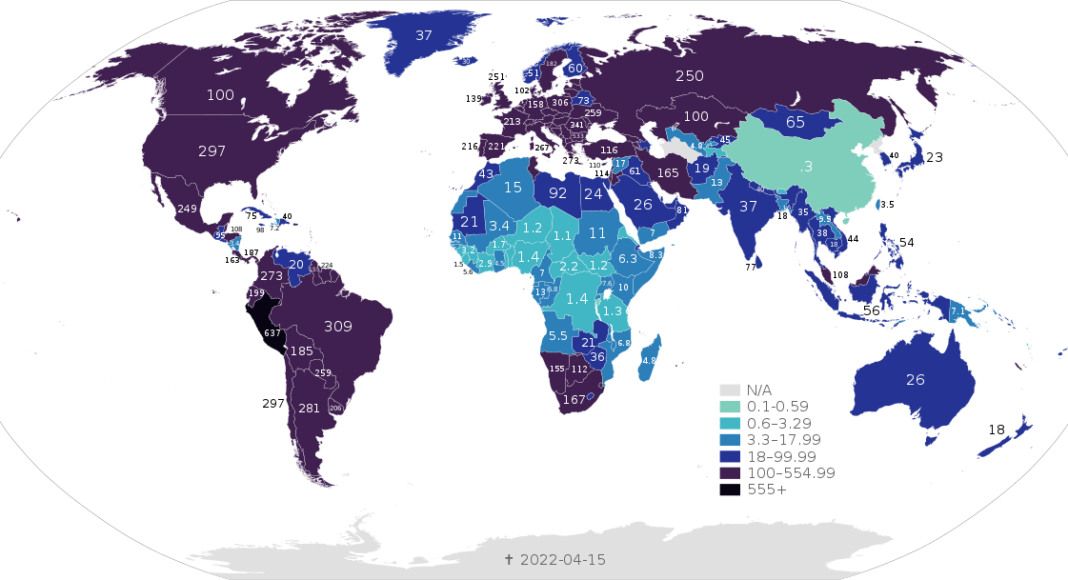

Main image: COVID-19 Outbreak World Map Total Deaths per Capita per 100,000 population, as of 15 April, 2022. CC BY-SA 4.0. Image courtesy of Dan Polansky and authors of File:BlankMap-World.svg.